Cent cinquante personnes sont venues pour un anniversaire des plus tristes : la commémoration de la destruction du village d’al-Araqib par la police israélienne, il y a quatre ans, le 27 juillet 2010. Anciens habitants du village, proches et membres des quelques familles qui vivent encore sur place, activistes israéliens venus exprimer leur solidarité, tout le monde se réunit sous les derniers arbres qui restent pour partager le repas de l’iftar, la rupture du jeûne de ramadan. Le cheikh prend la parole, remercie tout le monde d’être venu, et réitère l’importance du sumud, la volonté des habitants de résister et rester sur place. Le docteur Abu Freh, ancien habitant du village, insiste sur la définition de ce terme fondamental pour la lutte palestinienne en général. Le sumud : rester, résister pacifiquement, continuer à vivre - mais aussi, ajoute-t-il, rester humain.

One hundred and fifty people were there to mark the saddest of anniversaries: the commemoration of the destruction of the village of Al-Araqib by the Israeli police, four years ago on 27 July 2010. Former inhabitants of the village, friends and relatives and members of the few families that still live there, Israeli activists present to express their solidarity, everyone met under the last remaining trees to share the iftar meal that marks the end of the Ramadan fast. The sheikh thanked everyone for coming, and stressed the importance of sumud, the determination of the inhabitants to resist and remain in the village. Doctor Abu Freh, a former resident of the village, emphasised the definition of this term, a concept fundamental to the Palestinian struggle in general. Sumud : steadfastness, peaceful resistance, continuing to live, but also, he added, to remain human.

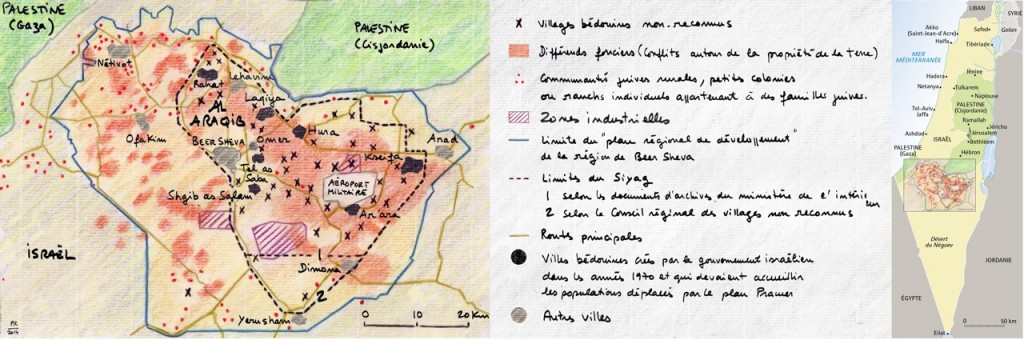

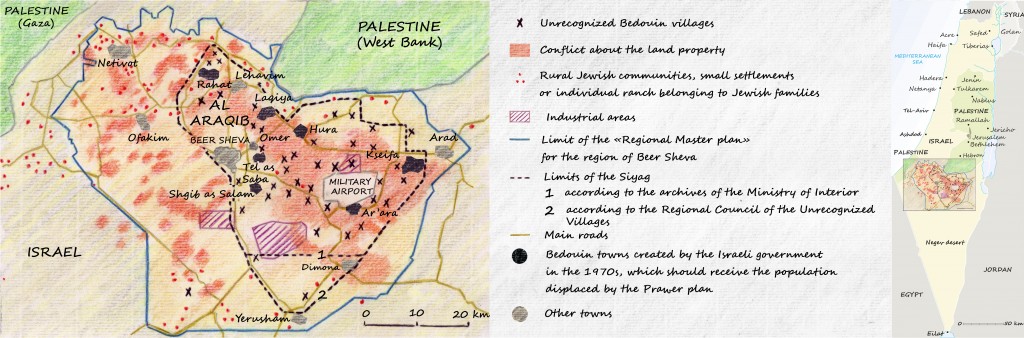

Les habitants d’al-Araqib, petit village bédouin proche de Beer Sheva, dans le sud d’Israël, luttent pour la survie de leur village et leur droit à rester sur les terres où il se trouvait. Comme une quarantaine d’autres villages dispersés dans le triangle formé par les villes de Rahat, Dimona et Arad, al-Araqib est un village fantôme, inexistant pour les autorités israéliennes : il n’est pas représenté sur les cartes, ni indiqué sur place, officiellement inaccessible aux ambulances et hors de portée des branchements aux divers réseaux publics, eau et électricité notamment... Le gouvernement considère ces villages comme illégaux et accuse leurs habitants d’ « envahir » et de « squatter » les terres de l’État, tandis que leurs habitants et les ONGs qui soutiennent leurs revendications les définissent comme « non-reconnus ». Leur statut actuel est en effet le résultat d’une politique très précise mise en place dès les années 1950 par le nouvel État hébreu.

The inhabitants of Al-Araqib, a small Bedouin village near Be’er Sheva in southern Israel, were fighting for the survival of their village and their right to remain on the land where it stood. Like some forty other villages scattered within the triangle formed by the towns of Rahat, Dimona and Arad, Al-Araqib is a ghost village, unrecognised by the Israeli authorities: it is not shown on maps, nor signposted locally, officially inaccessible to ambulances and unconnected to the various public networks, in particular water and electricity… The government considers these villages to be illegal and accuses their inhabitants of “invading” and “squatting on” state land, whereas their inhabitants and the NGOs that support their claims, define them as “unrecognized”. Their current status is in fact the result of a very specific policy introduced in the 1950s by the new Hebrew state.

Avec la création d’Israël et la guerre avec les pays arabes voisins, une grande partie des Bédouins du Néguev fuient vers la Jordanie, l’Egypte ou Gaza. Entre 1951 et 1953, ceux qui restent sont concentrés dans un espace appelé « Siyag » (clôture), correspondant au triangle où se trouvent encore aujourd’hui les villages non reconnus. Ce déplacement obligatoire, présenté comme devant durer six mois, prend fin en 1966, lorsque la loi martiale qui régit la vie des Palestiniens vivant en Israël depuis 1949 est levée. Un véritable arsenal législatif est mis en place dans l’intervalle, donnant à l’Etat les moyens légaux de s’approprier les terres palestiniennes et de contourner l’existence de titres de propriété en bonne et due forme. L’acquisition des terres commencées par le Fonds National Juif dès le début du XXème siècle se poursuit ainsi par d’autres moyens.

With the creation of Israel and the war with the neighbouring Arab countries, a large proportion of the Negev Bedouins fled to Jordan, Egypt or Gaza. Between 1951 and 1953, those who remained were concentrated within an area called the “Siyag” (permitted area), corresponding to the triangle where the unrecognized villages are now located. This forced displacement, scheduled to last six months, ended in 1966, with the lifting of the martial law that had governed the lives of Palestinians living in Israel since 1949. In the meantime, a veritable legislative arsenal was introduced, giving the State the legal means to appropriate Palestinian land and to bypass legally established property titles. The acquisition of land, begun by the Jewish National Fund in the early 20th century, thus continued by other means.

Deux lois notamment sont largement appliquées dans le Néguev : la loi sur la propriété des absents[1] adoptée en 1950, et la loi d’acquisition des terres[2] (1953). La première fait passer entre les mains d’un « Gardien » les propriétés des « absents » - définis entre autres comme tout citoyen palestinien qui aurait quitté son lieu habituel de vie pour un endroit extérieur à la Palestine avant le 1er septembre 1948, ou pour un endroit en Palestine tenu par des forces hostiles à Israël. La seconde permet au gouvernement de saisir les terres qui n’étaient pas en possession de leur propriétaire le 1 avril 1952 pour des motifs militaires ou de développement. Ces lois créent ainsi la catégorie des « déplacés internes » ; c’est dans cette catégorie schizophrénique, également appelée des « absents présents », que beaucoup de Bédouins du Néguev se trouvent encore aujourd’hui.

Two laws, in particular, were widely applied in the Negev: the Absentees Property Law,[1] adopted in 1950, and the Land Acquisition Law of 1953.[2] The first transferred the property of “absentees” to a “Custodian”. Absentees were defined, amongst other things, as any Palestinian citizens who had left their habitual place of residence for a place outside Palestine before September 1, 1948, or for a place within Palestine held by forces hostile to Israel. The second law allowed the government to seize land not in possession of its owner on April 1, 1952, for military or development purposes. These laws thus created the category of “internally displaced persons”, a schizoid classification also referred to as “present absentees”, which many Negev Bedouins still find themselves in today.

Les situations varient néanmoins selon les villages : certains, comme celui d’al-Sira, qui se trouvait déjà dans la zone du Siyag, n’ont jamais été déplacés. Dans ce cas, c’est la création d’un aéroport militaire à proximité qui a justifié les ordres de démolitions envoyés aux habitants à partir de 2006[3], arguant que les terres du village avaient été expropriées dès les années 1980.

Nonetheless, situations vary from one village to another: some, like the inhabitants of Al-Sira, which was already located in the Siyag zone, were never displaced. In this case, it was the creation of a military airport nearby which justified the demolition orders first sent to the inhabitants in 2006,[3] on the grounds that the village’s land had been expropriated in the 1980s.

Davantage de terre, moins d’Arabes : ce principe de base de la politique israélienne est appliqué avec continuité depuis les années 1950 au sein d’Israël aussi bien qu’en Cisjordanie. Les habitants d’al-Araqib et des autres villages non reconnus sont ainsi priés d’aller vivre dans une des sept villes créés dans les années 1970 pour les Bédouins. Rahat, à quelque vingt minutes de voiture d’al-Araqib compte 58 700 habitants[4]. C’est la plus grande ville bédouine d’Israël, où les enfants du village vont à l’école, et où la plupart des anciens habitants d’al-Araqib habitent désormais.

More land, fewer Arabs: this has been a basic constant of Israeli policy since the 1950s, both in Israel and on the West Bank. The inhabitants of Al-Araqib and of the other unrecognized villages were thus requested to go and live in one of the seven towns created for the Bedouins in the 1970s. Rahat, a twenty minute drive from from Al-Araqib, has a population of 58,700.[4] It is Israel’s biggest Bedouin town, where the children of the village go to school and where most of the former inhabitants of Al-Araqib now live.

Malgré l’échec social de ces « townships »[5], réputés pour leur niveau de vie extrêmement bas et des taux de criminalité souvent assez élevés, la ligne des différents gouvernements n’a pas varié dans le temps, le but étant toujours de sédentariser de force une population traditionnellement nomade et de libérer l’espace qu’elle occupe. Encore récemment, le Plan Prawer, promu par le gouvernement, visait à « réglementer l’établissement des Bédouins dans le Néguev » et prévoyait pour cela le déplacement de près de 40 000 personnes vers les villes bédouines. Le plan a été officiellement enterré le 12 décembre 2013 après qu’un de ses principaux architectes, Benny Begin, a déclaré à la Commission de l’intérieur et de l’environnement de la Knesset que les Bédouins n’avaient jamais été informés du contenu du plan et n’avaient donc jamais exprimé leur accord, contrairement à ce que le gouvernement affirmait. Très peu de temps après, la tâche de « réguler » la présence bédouine dans le Néguev a été confiée à Yaïr Shamir et au Ministère de l’agriculture et du développement rural, sur des bases inchangées.

Despite the social failure of these “townships”,[5] known for their extremely low standard of living and often rather high rates of criminality, the different government lines have not varied over time, the goal being always to impose sedenterisation on a traditionally nomadic people, and to free up the space they occupy. The purpose of the recent, government-backed Prawer Plan, was “the regulation of Bedouin settlement in the Negev”, including provisions to relocate almost 40,000 people to the Bedouin townships. The plan was officially buried on December 12, 2013 after one of its main architects, Benny Begin, told the Knesset’s Interior and Environment Committee that the Bedouin had never been informed of the contents of the plan and so had never given their consent, in contradiction of government claims. A very short time after, the task of “regulating” the Bedouin presence in the Negev was assigned to Yaïr Shamir and to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, on exactly the same principles as before.

Carte réalisée par Philippe Rekacewicz, reproduite avec l’aimable autorisation de l’auteur.

Map produced by Philippe Rekacewicz, and reproduced with the kind agreement of the author

Les habitants d’al-Araqib font partie de ces déplacés internes qui ont tenté de revenir sur leurs terres. En 1951 les familles furent déplacées, et assurées qu’elles pourraient revenir au bout de six mois. En 1953 cependant les terres furent déclarées terres de l’État ; lorsque une loi permit aux citoyens israéliens de soumettre leurs titres de propriété pour les faire enregistrer, les habitants d’al-Araqib présentèrent leurs dossiers, qui n’ont à ce jour toujours pas été traités, comme l’ensemble des demandes déposées à ce moment. La plupart des familles étaient alors dispersées, certaines vivant à Rahat, d’autres s’étant déplacées pour trouver du travail. Une cinquantaine de familles décida de retourner s’installer près du cimetière en 1998, lorsqu’il apparut que les terres étaient menacées par les plantations du Fonds national juif. Ils luttent désormais pour que le village et leurs droits sur ces terres soient reconnus.

The inhabitants of Al-Araqib are among the internally displaced persons who have tried to return to their land. The families were moved in 1951, on the assurance that they could return after six months. In 1953, however, the land was declared state property; when a law was introduced allowing Israeli citizens to submit their property titles for registration, the inhabitants of Al-Araqib presented their applications, which to this day have still not been processed, as is the case with all the applications so far submitted. Most of the families then dispersed, some to live in Rahat, others moving to find work. Around fifty families decided to return and settle near the cemetery in 1998, when it seemed likely that the land was under threat from the plantations of the Jewish National Fund. They are now fighting for the village and their rights over this land to be recognised.

Après l’aspersion des récoltes avec des herbicides en 2003 et 2004, la destruction du village et des cultures qui l’entouraient en 2010 et les quelques soixante-dix démolitions qui ont suivi, les terres du village ont finalement petit à petit été accaparées par les arbres du Fond national juif.

After the spraying of the harvests with herbicides in 2003 and 2004, the destruction of the village and the surrounding crops in 2010 and the seventy or so demolitions that followed, the village land has gradually been overrun by the trees of the Jewish National Fund.

Une autre étape dans la disparition progressive d’al-Araqib a été franchie le 12 juin 2014. Les bulldozers de l’ILA (Israel Land Administration) ont pénétré dans le cimetière qui servait de refuge aux dernières familles restant sur les terres de l’ancien village. Les quelques maisons, caravanes ou tentes, le nouveau minaret de la mosquée, les réserves d’eau, tout a été détruit et emporté[6]. Le grillage même, qui marquait les limites du cimetière, a été retiré : celles-ci doivent être redessinées de manière à englober moins de terre. Le traumatisme est d’autant plus grand que le cimetière, symbole du lien ancestral des Bédouins avec cette terre, était perçu depuis 2010 comme un espace protégé, où la police n’entrait pas - ou peu, uniquement de temps en temps pour faire des photos.

Another step in the steady erasure of Al-Araqib was taken on June 12, 2014. The bulldozers of the ILA (Israel Land Administration) entered the cemetery where the last remaining families on the former village land had taken refuge. The handful of houses, caravans and tents, the mosque’s new minaret, the water reserves… everything was destroyed and removed.[6] Even the fence that marked the margin of the cemetery was removed, so that the boundary could be redrawn to cover less land. The trauma was all the greater in that the cemetery, a symbol of the ancestral bond between the Bedouins and this land, had since 2010 been seen as a protected space, where the police did not enter, or entered only occasionally to take photos.

Quelques jours après, une nouvelle stratégie est employée : tout autour de l’ancienne enceinte du cimetière, et à l’intérieur, dans sa partie sud, la terre est labourée, creusée, retournée, empêchant tout retour et toute construction.

A few days later, a new strategy was employed: the land all around the former cemetery wall, and in the southern part of its interior, was excavated, dug up and turned, to prevent any return or future construction.

En haut, Al-Araqib en novembre 2013, en bas en juillet 2014. Photos Marion Lecoquierre.

Above, al-Araqib in November 2013, below, in July 2014. Pictures Marion Lecoquierre.

A gauche, l’arbre qui servait de lieu de retrouvailles et d’accueil aux habitants du village (novembre 2013). Au centre et à droite, le même arbre et ses environs après la destruction de juin 2014. Photos Marion Lecoquierre.

On the left, the tree that used to represent a place of reunion and reception (November 2013). In the center and on the right, the same tree and its surroundings after the destruction of June 2014. Pictures Marion Lecoquierre.

Un mois plus tard, les habitants sont toujours là. Le village, ou ce qu’il en reste, a été réorganisé, chaque famille conservant son espace. Haqma et Salim sont installés près du portail d’entrée : une tente et la vieille camionnette de Salim, vidée de ses sièges, servent de chambre aux enfants. Les parents dorment dans l’espace central, sous une bâche servant de toit. Plus de cuisine, de salle de bain, d’eau courante même. Le cheikh vit sous une tente igloo avec sa femme, et son fils Aziz a trouvé refuge avec sa famille dans le bâtiment qui sert de mosquée le vendredi. Les visages sont défaits et l’ambiance tendue. Sujjud et Ali, les plus jeunes enfants d’Haqma et Salim, continuent à jouer. Maryam, leur sœur, 23 ans, tente une plaisanterie : « On sera bien ici cet hiver hein !! ». Car bien sûr, il n’est pas question d’abandonner. Haia Noah, du Forum pour la coexistence dans le Néguev, laisse percer son admiration, malgré son inquiétude face à une telle situation : « Vivre dans ces conditions pendant un mois, personne d’autre n’aurait pu le faire ».

A month later, the inhabitants were still there. The village, or what remained of it, had been reorganised, with each family retaining its own space. Haqma and Salim had settled near the entry gate: a tent and Salim’s old van, its seats removed, served as the children’s bedroom. The parents were sleeping in the central space, using a tarpaulin as a roof. No more kitchen, bathroom, or even running water. The sheikh was living in an igloo tent with his wife, and his son Aziz had found shelter with his family in the building used as a mosque on Fridays. Faces were haggard and the atmosphere tense. Sujjud and Ali, Haqma’s and Salim’s youngest children, continued to play. Maryam, the 23-year-old sister, attempted a joke: “We’ll be comfortable here this winter!!” Because of course, there was no question of giving up. Haia Noah, from the Negev Coexistence Forum, could not hide his admiration, despite his concern about the situation: “Living for a month in these conditions, no one else could have managed it.”

A gauche, l’intérieur de la maison de Salim et Haqma Abu-Madighem en novembre 2013, avec la cuisine en arrière-plan. A droite, le campement organisé après la destruction de juin 2014. Photos Marion Lecoquierre.

On the left, inside the house of Salim and Haqma Abu-Madighem in November 2013, with the kitchen in the background. On the right, the camp organized after the destruction of June 2014. Pictures Marion Lecoquierre.

Deux femmes du village transportent un jerrycan d’eau à la tente du cheikh, Sayyah al-Turi, et de sa femme Aliyeh après que le mobile-home qu’ils occupaient a été emporté, juin 2014. Photo Marion Lecoquierre.

Two women of the village carry a jerrycan of water towards the tent of the Sheikh, Sayyah al-Turi, and his wife Aliyeh after the mobile-home they were living in was taken away, June 2014. Picture Marion Lecoquierre.

Le 17 juillet au matin, deux voitures, de l’ILA et de la « Patrouille verte »[7], viennent remettre une enveloppe aux habitants du village : un ordre de vider le cimetière de toutes leurs possessions matérielles. Avant le dimanche qui suit, soit trois jours. Le dimanche matin, 7 h, des membres de la famille sont venus de Rahat, ainsi que plusieurs activistes israéliens, surtout de Tel Aviv. Un grondement continu se fait entendre à l’horizon. Pas un orage, non, mais le bombardement de Gaza. Les hélicoptères qui passent en continu au-dessus du village contribuent à la création d’une atmosphère menaçante : hélicoptères de l’armée qui effectuent des exercices et se posent en face du village, mais aussi hélicoptères de la police qui passent et repassent au-dessus du village, portes ouvertes, pour observer l’assemblée qui s’y tient.

On the morning of July 17, two cars, from ILA and the “Green Patrol”,[7] turned up to deliver an envelope: an order to the inhabitants to remove all their material possessions from the cemetery. Before the coming Sunday, i.e. in three days. At 7am on the Sunday morning, family members came from Rahat, along with several Israeli activists, mainly from Tel Aviv. In the distance, a continuous rumbling. Not a thunderstorm, but the bombing of Gaza. The helicopters continuously overflying the village contributed to the menacing atmosphere: army helicopters on exercises, landing opposite the village, but also police helicopters flying back and forth overhead, doors open, to observe the assembly below.

Les habitants ont amassé le peu qu’ils possèdent (matelas, couvertures, casseroles…) dans les camionnettes, garées désormais en dehors des limites du cimetière. Le juge qui a examiné le dossier dans la matinée a donné sept jours pour évacuer. Tout : matériel et habitants. Le cheikh revient du tribunal : « S’il le faut, nous dormirons dans le cimetière, au milieu des tombes » affirme-t-il. Le sumud, toujours : rester, résister, et continuer à vivre. Les habitants se prennent à rêver à d’autres stratégies qui permettraient de passer entre les mailles du filet, de contourner les ordres reçus et de continuer à vivre dans le cimetière en déjouant la surveillance tout en pouvant en sortir rapidement quand nécessaire. Acheter des camions et dormir dedans serait une solution, explique Salim. Résonnent comme en écho les solutions utopiques évoquées par Haqma au cours des deux années passées : vivre sur un tracteur pour rentrer et sortir comme elle voulait du cimetière, ou même vivre sous terre… L’Etat ne pourrait plus dire qu’elle occupait ses terres.

The inhabitants had collected their few possessions (mattresses, blankets, saucepans…) in vans, now parked outside the cemetery boundary. The judge who examined the case in the morning had given them seven days to leave. Everything: possessions and people. The sheikh returned from the court: “If we have to, we will sleep in the cemetery, among the tombs”, he announced. Once again, sumud: remain, resist and continue to live. The inhabitants began imagining other strategies that would help them pass through the net, to bypass the orders and continue to live in the cemetery, regardless of the surveillance, while still being able to leave quickly when necessary. One solution proposed by Salim would be to buy trucks to sleep in. An echo of the utopian solutions suggested by Haqma over the previous two years: living on a tractor in order to enter and leave the cemetery at will, or even living underground… The State could no longer say that she was occupying its land.

L’inquiétude est là, pourtant. Les conditions de vie sont toujours plus dures, les chances de gagner toujours plus faibles, et, surtout, portent sur des points de plus en plus restreints. Le 1er octobre 2014, le tribunal de district a refusé la demande des habitants de pouvoir faire appel de l’ordre d’expulsion. Le 14, tous les abris ont été détruits, les véhicules et les possessions personnelles des habitants confisqués, y compris les matelas et les couvertures. Le cheikh et deux de ses fils ont été arrêtés, et relâchés le lendemain sans comparution devant le tribunal.

The anxiety, nevertheless, was palpable. Living conditions were growing harder, the chances of winning ever lower, and above all winning on an increasingly limited number of points. On October 1, 2014, the district court refused an application by the inhabitants to appeal against the expulsion order. On October 14, all the shelters were destroyed, the inhabitants’ vehicles and personal possessions confiscated, including mattresses and blankets. The sheikh and two of his sons were arrested, and then released the next day with no court appearance.

Aziz, un des fils du cheikh, est désabusé : «On pensait que la démocratie, le droit, les tribunaux existaient… Je suis à la fois Palestinien, de culture bédouine, musulman et citoyen israélien, pourquoi ça pose problème ? ». Le village cristallise cette identité multiple et les problèmes qu’elle pose. Il matérialise à la fois le lien avec la terre comme espace de vie, habitée, cultivée et cultivable, et l’enracinement des habitants dans un espace, une terre particulière sur laquelle ils ont des droits. En se promenant autour d’al-Araqib avec les habitants du village, le paysage s’anime d’un sens nouveau : ici s’arrêtent les terres de la famille Abu-Freh, ici s’étendent les parcelles du cheikh, et plus loin commence la propriété des Elokbi... Des citernes et les restes de vieilles maisons en pierre détruites en 1948 marquent l’emplacement de ces anciens lieux de vie. Aucune limite physique ne distingue les différentes propriétés, qui restent pourtant connues de tous.

Aziz, one of the sons of the Sheikh, was disillusioned: “We thought that there was such a thing as democracy, law, the courts… I am simultaneously a Palestinian, raised as a Bedouin, a Muslim and an Israeli citizen, why is that a problem?” The village crystallises this multiple identity and the problems it poses. It embodies both the link with the land as a living space, inhabited, cultivated and cultivable, and the inhabitants’ rootedness in space, a particular land over which they have rights. Walking around Al-Araqib with the village’s inhabitants, the landscape takes on a new meaning: here are the boundaries of the Abu-Freh family’s land, these are the plots belonging to the sheikh, over there the start of Elokbi property… Water tanks and the remains of old stone houses destroyed in 1948 mark the location of these former living places. No physical boundary marks the different plots, yet everyone knows where they are.

En 2011, le rapporteur spécial sur les droits des peuples autochtones désigné par l’ONU rappelait au gouvernement israélien son devoir de « protéger les droits des Bédouins à la terre et aux ressources dans le Néguev », soulignant l’importance culturelle et historique de leurs liens avec la terre où ils vivent (UN Human Rights Council, 2011, p. 27). La réponse du gouvernement fut catégorique : « l’État d’Israël n’accepte pas la classification de ses citoyens bédouins comme peuple autochtone » (ibid., p. 28).

In 2011, the UN appointed special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples reminded the Israeli government of its duty to “protect Bedouin rights to lands and resources in the Negev”, emphasising the cultural and historical importance of their links with the land where they live (UN Human Rights Council, 2011, p. 27). The government’s response was categorical: “The State of Israel does not accept the classification of its Bedouin citizens as an indigenous people” (ibid., p. 28).

Les villages bédouins ne sont vus que comme un symptôme de ce qui est en général considéré comme un « problème » ou un « phénomène ». La position des différents gouvernements israéliens vis-à-vis de la population bédouine a été explicitée de manière fameuse par Moshe Dayan en 1963, alors qu’il était ministre de l’Agriculture : « nous devrions transformer les Bédouins en un prolétariat urbain (…) sans coercition mais avec la direction du gouvernement, ce phénomène des Bédouins disparaîtra »[8].

The Bedouin villages are seen only as a symptom of what is generally considered to be a “problem” or a “phenomenon”. The position of the Israel’s different governments regarding the Bedouin population was famously characterised in 1963 by Moshe Dayan, then Minister of Agriculture: “we should transform the Bedouin into an urban proletariat (…) without coercion but with governmental direction… this phenomenon of the Bedouins will disappear.”[8]

La coercition s’est ajoutée aux avantages proposés aux Bédouins qui acceptent de quitter les villages et qui renoncent à leurs droits de propriété[9]. L’objectif reste inchangé : les Bédouins doivent s’intégrer et, à terme, disparaître. Le démembrement des villages non reconnus au profit des « townships » n’est qu’une étape de ce processus.

Coercion has been added to the benefits offered to Bedouins who accept to leave the villages and give up their rights of ownership.[9] The objective remains the same: the Bedouins must assimilate and, ultimately, disappear. The dismemberment of the unrecognized villages in favour of the “townships” is only one stage in this process.

A propos de l'auteure : Marion Lecoquierre est Doctorante en sociologie et géographie à l’Institut universitaire européen (Florence)

About the author: Marion Lecoquierre is a Doctoral researcher in sociology and geography at the European University Institute (Florence)

Pour citer cet article : Marion Lecoquierre, "Les villages invisibles d’Israël: vers la disparition des Bédouins du Néguev ?" justice spatiale | spatial justice, n° 7 janvier 2015, http://www.jssj.org/

To quote this article: Marion Lecoquierre, « Israel’s invisible villages: disappearance of the Negev Bedouin? » justice spatiale | spatial justice, n° 7 janvier 2015, http://www.jssj.org/

[6] Vidéo tournée par Silvia Boarini https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5rNv_zBixJ0.

[6]Video shot by Silvia Boarini https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5rNv_zBixJ0.

[7] La « Green Patrol », créée en 1976, a officiellement pour mission de protéger l’environnement et d’empêcher les utilisations illégales des terres de l’état. Elle agit pour le compte de différentes organisations gouvernementales : ILA, JNF, Ministères de la défense et de l’agriculture…

[7]The official mission of the “Green Patrol, created in 1976, is to protect the environment and to prevent illegal uses of state land.It acts on behalf of different governmental organisations:ILA, JNF, Ministries of Defence and Agriculture…

[9]En fonction de la taille des terres revendiquées, le gouvernement propose un dédommagement correspondant à un petit pourcentage de la valeur du terrain visé, valeur évaluée par le gouvernement, et/ ou un lopin de terre dans un township.

[9]Depending on the size of the land claim, the government offers compensation corresponding to a small percentage of the value of the plot in question, a value assessed by the government, and/or a a patch of land in a township.