Introduction

Introduction

Les mobilisations qui ont suivi les soulèvements révolutionnaires de l’année 2010-2011 en Tunisie ont révélé des problématiques tenues sous silence sous le régime autoritaire de Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. Ainsi, le fait que les foyers de la contestation aient été les régions de l’intérieur du pays a permis de « (re)découvrir la marginalisation et l’exclusion » de ces régions (Hibou, 2015, p. 99), de lever le voile sur une « asymétrie sociale et spatiale » qui apparaît « constitutive de l’État en Tunisie », et qui est « autant le produit d’une trajectoire pluriséculaire que la résultante du protectorat et du capitalisme » (Hibou, 2015, p. 148). Il faudrait cependant se garder d’opposer trop schématiquement régions de l’intérieur et régions littorales, celles-ci n’étant pas homogènes ; des fractures sociospatiales existent également à d’autres échelles, comme entre les grandes villes et leurs arrière-pays, ou entre différents quartiers d’une même ville (Daoud, 2011). En outre, les demandes nationales se sont accompagnées de revendications spécifiques aux régions dans lesquelles elles émergeaient. Dans certains territoires, elles ont fait la part belle à des thématiques environnementales autour de l’accès aux ressources et du cadre de vie, mettant en cause, là aussi, la ségrégation régionale.

The protests that followed the revolutionary uprisings in Tunisia in 2010-2011 revealed problems that had remained unspoken under the authoritarian regime of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. The fact that the focal points of the protest had been regions within the country led to the “(re)discovery of the marginalisation and exclusion” of these regions (Hibou, 2015, p. 99), lifted the veil on a “social and spatial asymmetry” that seemed “constitutive of the state in Tunisia” and was “as much the outcome of a centuries-long process as of the protectorate and of capitalism” (Hibou, 2015, p. 148). However, one should be careful not to draw over-simplistic contrasts between the interior and coastal regions, since the latter are not homogeneous: sociospatial fractures also exist at other levels, for example between the big cities and their hinterlands, or between different districts of a single city (Daoud, 2011). In addition, the national demands were accompanied by claims that were specific to the regions where they emerged. In certain areas, their particular focus was on environmental issues around access to resources and living conditions, once again raising the question of regional segregation.

Les occupations et les blocages des décharges ont mis en lumière leur état sanitaire et environnemental déplorable, les impacts sur les quartiers riverains et la mauvaise gestion institutionnelle des déchets (Loschi, 2019). Les protestations autour des structures de gestion de l’eau en milieu rural ont montré l’iniquité de l’accès à cette ressource (Gana, 2013). De multiples sit-in et blocages de route contre les coupures d’approvisionnement en eau se reproduisent chaque année, mettant en cause des politiques de gestion de l’eau qui lèsent certaines régions. S’y sont ajoutées des occupations de terres collectives au nom de légitimités historiques (Gana et Taleb, 2019) et des manifestations pour la fermeture de sites industriels jugés dangereux ou demandant une limitation de leurs nuisances.

The occupation and picketing of landfill sites highlighted their terrible sanitary and environmental conditions, their impact on local neighbourhoods and the poor management of waste at institutional level (Loschi, 2019). The protests around water management structures in rural areas showed the inequalities in access to water (Gana, 2013). Every year, there are multiple sit-ins and road blockades in protest against water supply cuts, publicising water management policies that negatively affect certain regions. In addition, public land has been occupied on grounds of historical legitimacy (Gana and Taleb, 2019), and there are demonstrations calling for the closure of industrial sites perceived as dangerous or for improvements to environmental practices.

Ces mobilisations locales se sont emparées de la thématique environnementale avec des entrées qui la mêlent à des questions sociales et territoriales et se distinguent des approches par le haut promues par l’État[1] et certaines ONG. La contestation des dégradations environnementales qui touchent le lieu de vie se croise avec des revendications de dignité et une dénonciation d’injustices perçues comme étant subies de manière collective et géographique[2]. Ces mobilisations se rapportent à des « conflits de lieux » (Dechézelles et Olive, 2019) qui mettent en jeu des identités collectives et contribuent à les redéfinir.

These local protests tackle the environmental issue from perspectives that include social and territorial questions, demanding a change from the top-down approaches promoted by the state and certain NGOs.[1] The complaints about environmental hazards that affected their homes are combined with demands for respect and a condemnation of injustices experienced both collectively and geographically.[2] These protests relate to “conflicts of places” (Dechézelles and Olive, 2019) that bring into play and contribute to the redefinition of collective identities.

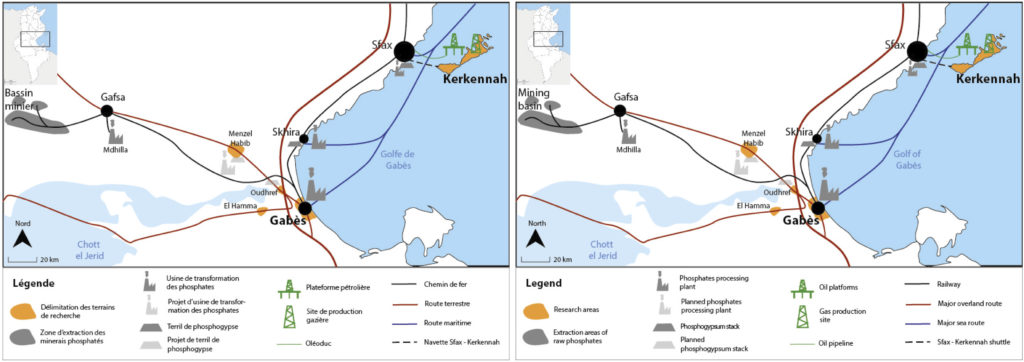

Dans cet article, nous nous penchons sur deux territoires situés autour du golfe de Gabès, sur la partie est du littoral tunisien. Ils ont en commun d’avoir été le théâtre de mobilisations mettant en cause les nuisances environnementales d’activités industrielles après 2011 (voir figure 1). Le premier, Gabès, est le chef-lieu du gouvernorat du même nom. Ce grand port du Sud tunisien, avec ses 150 000 habitant·te·s, abrite un important complexe industriel de transformation des phosphates extraits dans le bassin minier de Gafsa et acheminés à Gabès par le chemin de fer. Le deuxième, Kerkennah, est un archipel au large de la ville de Sfax, à laquelle il est relié par une navette maritime. L’archipel compte 16 000 habitant·te·s à l’année, cette population est décuplée l’été. Son sous-sol recèle de réserves de gaz et de pétrole qui sont exploitées par deux sociétés : TPS, qui extrait du pétrole sur des plateformes off-shore proches du rivage nord-ouest de l’archipel, et Perenco (ayant remplacé Petrofac en 2018) qui puise du gaz sur l’île Chergui.

In this article, we look at two areas situated around the Gulf of Gabès, on the eastern part of the Tunisian coast, which were both arenas of protest against bad environmental practices by industrial complexes after 2011 (see figure 1). The first, Gabès, is the capital city of the governorate of the same name. A big port in southern Tunisia with a population of 150,000, it is host to a large industrial complex for the processing of phosphates that are extracted from the Gafsa mining basin and transported to Gabès by rail. The second, Kerkennah, is a group of islands off the city of Sfax and linked to it by a sea shuttle, with a permanent population of 16,000 people, which increases tenfold in summer. It has underground reserves of gas and oil that are exploited by two companies: TPS, which extracts oil through offshore platforms close to the north-eastern edge of the island group; and Perenco (which replaced Petrofac in 2018) which drills for gas on Chergui Island.

Figure 1 : Carte des terrains de recherche (illustration de l’auteur).

Figure 1: Map of research sites (illustration by author).

Les activités industrielles s’y sont implantées à des époques différentes et suivent des configurations distinctes (acteurs publics et privés). À Gabès, l’activité industrielle chimique est présente depuis 1972. Elle est le fruit d’une politique publique d’industrialisation nourrie par une idéologie moderniste et promue comme voie de décolonisation (Signoles, 1985) et s’organise aujourd’hui autour d’une entreprise étatique, le Groupe chimique tunisien (GCT), qui transforme les minerais phosphatés extraits dans le bassin minier en acide phosphorique et en engrais. Quelques entreprises privées se sont greffées au complexe. À Kerkennah, l’activité d’extraction pétrogazière date des années 1990. Elle est menée par des sociétés privées multinationales, mais l’Entreprise tunisienne des activités pétrolières (ETAP), entreprise publique, détient la moitié des parts des permis d’exploitation, ce qui constitue une ressource financière pour l’État.

The industrial activities were set up there at different times and are run by different combinations of public and private actors. In Gabès, there has been a chemicals industry since 1972. It is the product of a public policy of industrialisation fed by a modernising ideology and promoted as a pathway to decolonisation (Signoles, 1985), and is structured today around a state enterprise, the Tunisian Chemicals Group (GCT), which converts phosphates extracted from the mining basin into phosphoric acid and fertiliser. A few private companies have attached themselves to the complex. In Kerkennah, oil and gas drilling dates back to the 1990s. It is conducted by private multinational firms but the public company Tunisian Oil Activity Enterprise (ETAP) holds a half share in the operating permits, which provides a source of revenue for the government.

Ces deux territoires ont en commun la coexistence de l’industrie avec d’autres activités, notamment dans le secteur primaire, ainsi que la prégnance du chômage, en particulier chez les jeunes. L’économie de Gabès a longtemps reposé sur l’agriculture, la pêche et une fonction de carrefour. Le taux de chômage y atteint 25,4 % des actif·ve·s, contre 15,4 % au niveau national[3]. À Kerkennah, la plupart des habitants vivent de la pêche. La population y est vieillissante, car une large part des habitant·te·s les plus jeunes partent sur le continent pour poursuivre leurs études et trouver du travail.

What these two areas have in common is the coexistence of industry with other activities, notably in the primary sector, as well as high levels of unemployment, particularly among young people. For a long time, the economy of Gabès was reliant on farming, fishing and its status as a hub. It has an unemployment rate of 25.4%, compared with 15.4% for the country as a whole.[3] In Kerkennah, most of the inhabitants live from fishing. Its population is ageing because a large percentage of the youngest people move to the mainland to study and find work.

La contestation des nuisances environnementales induites par les activités industrielles à Gabès et à Kerkennah existait sous le régime autoritaire de Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, quoique circonscrite à certains secteurs – pêche, agriculture – ou à des cercles fermés. Mais la chute du régime en janvier 2011 a constitué une remarquable ouverture des opportunités politiques pour une multiplicité d’acteur·trice·s protestataires, donnant lieu à un élargissement des bases de la contestation, à une intensification de l’action collective et au recours à de nouveaux modes d’action.

Protests against the environmental damage caused by industrial activities in Gabès and Kerkennah existed under the authoritarian regime of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, although limited to certain sectors—fishing, farming—or to circumscribed areas. However, the fall of the regime in January 2011 opened up significant political opportunities for many protest groups, resulting in a broadening of the protest base, an intensification of collective action and the adoption of new modes of action.

Dans la région de Gabès, dès début 2011, des contestations localisées et ponctuelles contre les nuisances environnementales de l’industrie phosphatière combinées à des campagnes de mobilisation au niveau de la ville, et qui se sont structurées au cours des années suivantes, ont lancé de véritables dynamiques conflictuelles. À Kerkennah, dès 2011, les demandes de création d’emplois émises par les jeunes chômeur·se·s et les protestations des pêcheurs contre les fuites de pétrole se sont établies en séquences de mobilisations plus ou moins intenses entrecoupées de périodes creuses.

In the Gabès region, occasional local protests about the pollution produced by the phosphate industry in the early months of 2011, combined with the emergence of citywide protests in subsequent years, launched a cycle of conflict. In Kerkennah, demands for job creation by unemployed youngsters and fishermen’s protests against oil spills came together in sequences of activism of varying intensity interspersed with periods of calm.

Ces mobilisations locales interrogent la répartition des nuisances et des bénéfices de l’activité industrielle et font appel à des représentations partagées et territorialisées de l’(in)justice ainsi que des identités collectives imbriquant plusieurs niveaux d’échelles. Elles sont profondément ancrées dans les contextes locaux et fondées sur les pratiques quotidiennes. Elles s’appuient sur une imbrication de diverses formes organisationnelles, faisant intervenir des structures associatives, syndicales, mais aussi des collectifs constitués sur la base d’affiliations communautaires et de réseaux d’interconnaissance liés à des sociabilités quotidiennes. Nous reprenons ainsi à notre compte « l’hypothèse d’un processus d’hybridation entre les liens dits “communautaires” et les liens dits “citoyens” » au sein des mobilisations dans les pays de la Méditerranée (Ben Néfissa, 2011, p. 12)[4].

These local actions raise questions about the distribution of pollution and profits from industrial activity, and drew on shared and territorialised representations of injustice and collective identities at multiple and overlapping scales. They are profoundly embedded in local contexts, founded on day-to-day practices. They rely on a variety of entangled organisational forms involving civil society and union structures, but also collectives rooted in community affiliations and acquaintanceship networks linked with day-to-day social relations. We therefore adopt “the hypothesis of a process of hybridisation between so-called ‘community’ ties and so-called ‘citizenship’ ties” within protest movements in the Mediterranean countries (Ben Néfissa, 2011, p. 12).[4]

La notion de communauté à laquelle nous faisons référence ne correspond pas à un « moment » communautaire qui serait antérieur à un « moment » associatif ou citoyen plus évolué dans l’histoire des organisations (Jacquier, 2011). Elle se rapporte à une densité de liens sociaux au niveau local et un attachement des habitant·e·s au lieu qui constituent à la fois des enjeux et des ressources pour les mobilisations. On reprendra ici la définition qu’en donne Jean-François Médard : « à la fois un endroit, des gens vivant en cet endroit, l’interaction entre ces gens, les sentiments qui naissent de cette interaction, la vie commune qu’ils partagent et les institutions qui règlent cette vie » (Médard, 1969, p. 18).

As used here, these notions do not refer to a moment of community that preceded a more evolved civil society or a moment of citizenship in the history of the organisations (Jacquier, 2011). They refer to a density of social ties at local level, and the attachment to place, which constitute both challenges and resources for protest movements. The definition of community we adopt here is Jean-François Médard’s: “simultaneously a place, people living in that place, the interaction between those people, the feelings that arise from that interaction, the common life they share and the institutions that govern that life” (Médard, 1969, p. 18).

À rebours d’une approche qui postulerait d’emblée « la logique communautaire contre la justice » (Lévy, Fauchille et Póvoas, 2018, p. 254), nous nous intéressons aux manières dont des communautés se sont emparées des questions de justice dans la contestation des nuisances environnementales qu’elles subissent, et dont les actions, ainsi que les réactions qu’elles suscitent, participent à reconfigurer les disparités territoriales. L’idée de cet article est donc moins d’examiner ces enjeux à l’aune des théories centrées sur l’individu et prétendant à l’universel (Rawls, 1971) que de suivre l’invitation de Iris Marion Young à questionner la justice et l’injustice à partir de contextes sociaux particuliers et en lien avec des processus qui génèrent des inégalités (Young, 1990).

By contrast with an approach that immediately postulates the “community logic against justice” (Lévy, Fauchille and Póvoas, 2018, p. 254), we are interested in how communities have taken up questions of justice in protesting against the environmental burdens they experience, and how their actions, as well as the reactions they generate, contribute to the reshaping of territorial disparities. The aim of this article is thus less to examine these issues in the light of theories that focus on the individual and lay claim to universality (Rawls, 1971), than to accept Iris Marion Young’s invitation to explore justice and injustice in terms of particular social contexts and in relation to processes that generate inequalities (Young, 1990).

Nous verrons en première partie que le niveau local est celui où sont perçues les nuisances et que les mobilisations qui s’y rapportent s’appuient en grande partie sur des réseaux de proximité. En deuxième partie, nous examinerons les manières dont la dénonciation des dégradations environnementales s’ancre dans la contestation de la ségrégation régionale, et se nourrit de récits de spoliation ainsi que d’affirmations identitaires. Enfin, nous nous pencherons sur l’instrumentalisation des appartenances communautaires dans les réponses aux mobilisations qui tend à fragmenter les mouvements au niveau microlocal.

In the first part, we will see that the local level is the scale at which the burdens are perceived, and that the protests about them draw in large part on proximity networks. In the second section, we will examine how the denunciation of environmental damage is anchored in protest against regional segregation and is fed by narratives of dispossession and identity claims. Finally, we will look at how community membership is exploited in the responses to the protests, with the result that the movements tend to break down at microlocal level.

L’article se base sur des recherches de terrain qui se sont déroulées entre 2017 et 2019 à Gabès et Kerkennah dans le cadre d’une thèse de doctorat en géographie. Les données utilisées dans cet article ont été collectées par le moyen d’entretiens (principalement avec des acteurs des mobilisations, mais aussi, dans une moindre mesure, des responsables d’agences de l’État et d’entreprises), d’observation in situ de mobilisations à Gabès et de lecture de rapports et documents administratifs.

The article is based on field research conducted between 2017 and 2019 in Gabès and Kerkennah for a PhD thesis in geography. The data used in the article were collected through interviews (mainly with people involved in the protests, but also, to a lesser degree, officials in government agencies and businesses), through in situ observation of protests in Gabès, and from reading administrative reports and documents.

Le rôle des réseaux de proximité dans la mobilisation contre les nuisances environnementales de l’industrie à Gabès et Kerkennah

The role of proximity networks in activism against environmental hazards caused by industry in Gabès and Kerkennah

À Gabès comme à Kerkennah, le caractère éminemment localisé des nuisances environnementales des activités industrielles détermine la prise en charge de leur contestation par des collectifs organisés à un niveau local et des réseaux de proximité, sans toutefois s’y limiter. Les nuisances affectent, voire mettent en péril des lieux, les ressources matérielles qu’ils renferment, les usages qui en sont faits, mais aussi l’attachement symboliques et affectifs qui les lient à celles et ceux qui les pratiquent. L’exposition aux nuisances environnementales est spatialement différenciée : les différentes localités ne sont pas affectées de la même manière, ce qui donne lieu à des revendications locales spécifiques à différents groupes ancrés dans différents territoires.

In both Gabès and Kerkennah, the very local nature of the environmental hazards caused by industrial activities explains why the protest movements against them are mainly—though not exclusively—driven by locally organised groups and proximity networks. Industrial pollution affects or even menaces localities, the material resources within them, the uses made of them, but also the symbolic and emotional attachments that link them to the people who use them. Exposure to environmental hazards is spatially differentiated: the different localities are not affected in the same way, which gives rise to local claims that are specific to different groups with roots in different areas.

Les pratiques quotidiennes et les relations y compris hiérarchiques entre les membres de la communauté constituent le terreau de l’organisation de l’action collective (laquelle peut aussi contribuer à les remanier). Elles donnent lieu, par exemple, à un partage genré du travail de mobilisation : ce sont plus souvent les hommes qui organisent les actions ; les femmes sont minoritaires (mais présentes) dans les manifestations, mais leur participation y est encouragée à certaines occasions. En outre, des femmes ont su s’imposer lors de sit-in ou ont pris des initiatives qui ont poussé le reste de la communauté à se soulever.

The day-to-day practices and the relations, including hierarchical relations, between the members of the community constitute the bedrock of the organisation of collective action (which can also contribute to reshaping those practices and relationships). They give rise, for example, to a gendered division of activist roles: it is usually the men who organise protest actions; women are a minority (though present) at demonstrations, but their participation is encouraged on certain occasions. In addition, women have taken charge at sit-ins, or have taken initiatives that have prompted the rest of the community to join in.

Dans la région de Gabès, une pluralité de mobilisations localisées autour de l’industrie phosphatière

In the Gabès region, multiple localised protests around the phosphate industry

L’activité industrielle à Gabès engendre divers types de nuisances qui sont perçues et contestées au niveau de l’agglomération, voire au niveau des différents quartiers ou villages environnants. Les émissions gazeuses des unités affectent largement les localités situées autour de la zone industrielle de Gabès, principalement Ghannouch, Bouchemma, Chenini et Chott Salem, avec des concentrations de polluants[5] particulièrement élevées qui occasionnent des dommages sur la santé des habitant·e·s (cancers, maladies respiratoires) et sur les cultures[6]. Elles donnent lieu à des contestations qui s’appuient sur les différents quartiers, mais dont les revendications communes se rejoignent. Les agriculteurs des oasis ont esté en justice dès les années 1980 pour obtenir des compensations de la part de certaines entreprises de la zone industrielle, compensations qui sont distribuées aux détenteurs de parcelles oasiennes des localités alentour (entretiens avec des responsables des entreprises Alkimia, ICF [octobre 2018] et du Groupe chimique tunisien [février 2019]). Après 2011, les demandes de réduction des émissions de gaz polluants ont fait partie des revendications exprimées lors de manifestations ayant rassemblé, dans l’agglomération de Gabès, plusieurs milliers de participant·e·s à plusieurs reprises[7].

Industrial activity in Gabès generates different types of hazards that are perceived and opposed at the scale of the city, or even of different neighbourhoods or villages in and around the city. Gas emissions from the units have a substantial impact on localities situated around Gabès industrial zone, mainly Ghannouch, Bouchemma, Chenini and Chott Salem, with particularly high pollutant concentrations[5] that cause damage to the health of local people (cancers, respiratory disorders) and to crops.[6] They have triggered protest movements that arise in the different neighbourhoods but come together around common demands. The farmers in the oases went to court in the 1980s to obtain compensation from certain companies in the industrial zone, compensation that was distributed to holders of oasis plots in the surrounding localities (interviews with representatives of the firms Alkimia, ICF [October 2018] and officials of the Tunisian Chemicals Group [February 2019]). After 2011, reductions in polluting gas emissions were among the demands expressed in substantial demonstrations in the conurbation of Gabès, with participants numbering in the thousands on several occasions.[7]

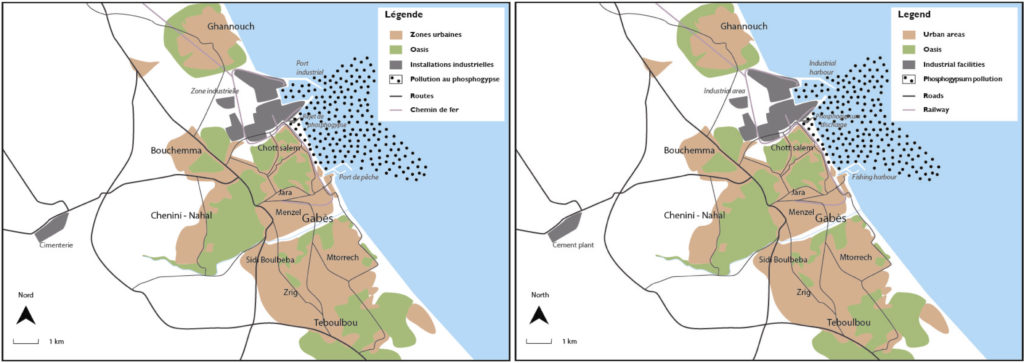

Figure 2 : L’agglomération de Gabès (illustration de l’auteur).

Figure 2: The city of Gabès (illustration by the author).

Les rejets de polluants liquides et solides dans le golfe de Gabès portent plus spécifiquement atteinte au cadre de vie des habitant·e·s des localités de bord de mer : Ghannouch et surtout Chott Salem (voir figure 2), qui jouxte le lieu de déversement massif d’une boue gypseuse, le phosphogypse, déchet du processus de transformation du phosphate en acide phosphorique, à raison de 12 000 tonnes par jour. Ce quartier a été très présent dans les dynamiques de mobilisation gabésiennes : plusieurs manifestations y ont eu lieu pour demander l’arrêt du déversement de phosphogypse, notamment la campagne Saker lemsab (Fermez le déversement) au printemps 2017, portée par une assemblée d’associations locales[8], mais qui s’est structurée autour de discussions tenues dans des cafés, lieux de sociabilité masculine quotidienne[9]. Ces rejets marins nuisent aussi aux revenus des pêcheurs de la région. Ces derniers se sont mobilisés à plusieurs reprises pour demander la fin des rejets polluants et obtenir des dédommagements de la part des industriels. Ceux-ci se rassemblent au niveau des localités où ils travaillent[10].

The discharge of liquid and solid pollutants into the Gulf of Gabès more specifically effects the living environment of people living in coastal localities—Ghannouch and in particular Chott Salem (see figure 2)—which are adjacent to a mass outlet for the discharge of 12,000 tonnes a day of a gypsum sludge called phosphogypsum, a byproduct of the process of converting phosphate into phosphoric acid. This district has been heavily involved in protest dynamics in Gabès: several demonstrations have been held there to demand a stop to the discharge of phosphogypsum, in particular the Saker lemsab (Shut the Discharge) campaign in spring 2017, headed by a collection of local organisations[8] but structured around conversation in the cafes, a day-to-day meeting place for men.[9] These discharges into the sea also affect the revenues of the region’s fisherperson who have taken action on several occasions to demand the end of waste discharges and compensation from the industrial firms. These fishermen join forces in the localities where they work.[10]

D’autres protestations surviennent en réaction à des incidents localisés, qui se produisent fréquemment à l’occasion du redémarrage des unités de production du GCT. Le 5 mai 2017, à la suite d’une fuite de gaz dans la zone industrielle, les enfants d’une école de Bouchemma ont éprouvé d’importantes gênes respiratoires. Les mères ont alors entrepris de bloquer la route menant à Gabès en signe de protestation contre les risques sur la santé causés par la proximité de la zone industrielle et lancé une grève générale circonscrite à Bouchemma quelques jours plus tard. Ce climat de mécontentement a favorisé le lancement d’un sit-in mené par de jeunes chômeurs de la localité devant le site du projet Nawara conduit par l’entreprise OMV (transfert de gaz) afin de demander des emplois ou le financement de projets entrepreneuriaux (entretien avec l’un des initiateurs du sit-in, avril 2018). Les agriculteur·ice·s de l’oasis de Bouchemma ayant constaté des « brûlures » dans leurs cultures se sont quant à eux mobilisés pour obtenir des dédommagements.

Other protests arise in reaction to local incidents, which occur frequently when the GCT’s production units restart. On 5 May 2017, following a gas leak in the industrial zone, children at a school in Bouchemma experienced significant breathing problems. The mothers then began blocking the road leading to Gabès as a protest against the health risks resulting from the proximity of the industrial zone, and a few days later initiated a general strike in Bouchemma alone. This climate of discontent led to the start of a sit-in, headed by young unemployed from the locality, in front of the site of the Nawara project (gas transfer) run by the firm OMV, to demand jobs or funding for entrepreneurial projects (interview with one of the initiators of the sit-in, April 2018). For their part, when farmers in the Bouchemma oasis observed “scorching” in their crops, they took action to obtain compensation.

Un projet de stockage de phosphogypse sous forme de terril est à l’étude depuis la fin des années 1990, sous pression internationale – le golfe de Gabès ayant été identifié comme « point chaud de pollution » par le Programme des Nations unies pour l’environnement. Un financement, par le biais d’un prêt, a été proposé par la Banque européenne d’investissement. C’est sous le gouvernement de Ben Ali qu’un premier site a été décrété, à proximité d’Oudhref (à une vingtaine de kilomètres de Gabès). Mais au lendemain de la chute du régime, la population d’Oudhref a manifesté fermement son opposition, à plusieurs reprises, par des grèves générales et des marches à travers la ville. Là encore, si ces mobilisations ont eu lieu à l’initiative des associations locales (entretien avec le maire d’Oudhref, membre de l’association Beit el kheir [« la maison de la charité »] et très investi dans l’opposition au terril de phosphogypse dans la période post-2011, avril 2019), l’activation des réseaux familiaux et de voisinage a permis qu’elles rassemblent une grande partie des habitant·e·s de la ville.

A plan to store phosphogypsum in slag heaps has been under consideration since the late 1990s, under international pressure since the Gulf of Gabès is identified as a “pollution hotspot” by the UN Environment Programme. Funding was offered by the European Investment Bank in the form of a loan. It was still under the Ben Ali regime that a first site was earmarked near Oudhref (some 20 km from Gabès). However, immediately following the fall of the regime, the population of Oudhref several times manifested its strong opposition by means of general strikes and marches through the city. Here again, while these actions were initiated by local organisations (interview with the Mayor of Oudhref, a member of the Beit el kheir Association ([“the house of charity”] and very strongly committed to opposing the phosphogypsum slag heap in the post-2011 period, April 2019), it was through the activation of family and neighbourhood networks that they were able to bring together a large proportion of the town’s inhabitants.

Le 5 décembre 2018, le gouvernement a annoncé s’être prononcé pour un site dans la délégation de Menzel El Habib, appartenant également au gouvernorat de Gabès, qui accueillerait cette fois non seulement le terril de phosphogypse, mais aussi de nouvelles unités de production du Groupe chimique tunisien censées remplacer celles de la zone industrielle de Gabès. Le conseil municipal, les associations et les sections locales des syndicats ont immédiatement clamé leur refus du projet, mais, selon la maire de la commune (entretien avec la maire de Menzel El Habib élue en mai 2018, en partie grâce à sa détermination à contester le projet de nouvelle zone industrielle à Menzel El Habib, avril 2019), les habitant·e·s sont divisé·e·s : certain·e·s espèrent pouvoir vendre leurs terres ou obtenir des emplois[11], quand d’autres craignent l’impact sur la nappe phréatique, cette région étant essentiellement agricole. Le conseil municipal, les organisations syndicales et associatives de la délégation voisine d’El Hamma se sont joints au mouvement d’opposition, organisant là encore des rassemblements, des marches et une grève générale très suivie le 10 décembre[12].

On 5 December 2018, the government announced that it had chosen a site in the Menzel El Habib delegation belonging to the same Gabès governorate, which would now become home not only to the phosphogypsum slag heap, but also new Tunisian Chemicals Group production units intended to replace those in the Gabès industrial zone. The municipal council, civil society organisations and local union sections immediately manifested their rejection of the project but, according to the town’s mayor (interview with the mayor of Menzel El Habib, elected in May 2018 partly because of her determination to oppose the planned new industrial zone in Menzel El Habib, April 2019), the population is divided: some hope to be able to sell their land or get jobs,[11] whereas others are worried about the impact on the water table in a predominantly agricultural region. The municipal council and union and civil society organisations in the neighbouring delegation of El Hamma joined the opposition movement, once again organising gatherings, marches and a widely followed general strike on 10 December.[12]

La lutte contre les pollutions de l’industrie du phosphate dans la région de Gabès n’est donc pas unifiée. Elle est portée par une pluralité de mobilisations en rapport avec des revendications spécifiques liées au caractère localisé des nuisances qui s’appuient largement sur des réseaux de proximité et des tissus de sociabilité du quotidien.

The struggle against pollution from the phosphate industry in the Gabès region is not a unified movement. It is impelled by multiple movements reflecting specific demands linked with the localised nature of the environmental hazards and largely reliant on proximity networks and networks of day-to-day social relations.

À Kerkennah, entremêlement de conflits autour des entreprises pétrogazières

In Kerkennah, interwoven conflicts around oil and gas industries

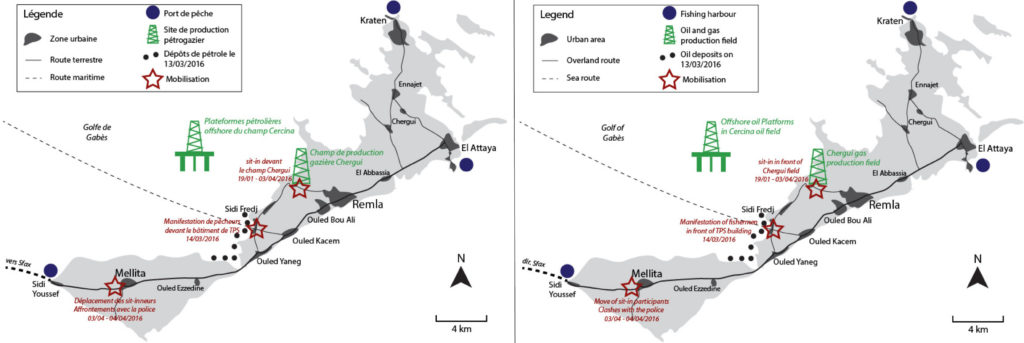

À Kerkennah, la pollution causée par les entreprises pétrogazières est moins manifeste et omniprésente qu’à Gabès, et ce sont principalement les fuites d’hydrocarbures issues des plateformes off-shore qui cristallisent la contestation des nuisances industrielles. En plus de la surpêche et de l’emploi de techniques destructrices des fonds marins (pêche au chalut), ces fuites contribuent à fragiliser les revenus des pêcheurs, sans oublier un effet délétère sur le tourisme. En mars 2016, les dépôts de pétrole sur la plage à côté de la zone touristique de Sidi Fredj ont donné lieu à un mouvement de protestation de pêcheurs et d’habitants de Mellita, d’Ouled Kacem et d’Ouled Yaneg (localités situées à proximité des déversements, voir figure 3) mettant en cause l’entreprise pétrolière TPS. De petits groupes ont organisé des rassemblements devant les locaux de l’entreprise (entretiens avec plusieurs pêcheurs investis dans la dénonciation des nuisances de TPS, octobre 2018). Des pêcheurs, soutenus par des associations locales[13], ont tenté d’engager des actions en justice, avant de renoncer à cause de la difficulté à s’acquitter des frais d’avocats et d’expertise.

In Kerkennah, the pollution caused by the oil and gas companies is less obvious and ubiquitous than in Gabès, and the target of protests against industrial hazards is mainly hydrocarbon leaks from the offshore platforms. Alongside overfishing and the use of techniques that damage the seafloor (trawling), these leaks are instrumental in threatening the revenues of the fisherpeople, as well as having a deleterious effect on tourism. In March 2016, oil deposits on the beach next to the Sidi Fredj tourist area triggered a protest movement by fishermen and residents of Mellita, Ouled Kacem and Ouled Yaneg (localities situated near the discharges, see figure 3), which blamed the oil company TPS. Small groups held gatherings in front of the firm’s premises (interviews with several fishermen involved in protests against environmental damage caused by TPS, October 2018). Fishermen, supported by local organisations,[13] tried to institute court proceedings, but eventually gave up because of the difficulty of paying the fees for legal and technical representation.

Figure 3 : Carte de Kerkennah (illustration de l’auteur).

Figure 3: Map of Kerkennah (illustration by the author).

Ce mouvement est survenu en plein sit-in de chômeur·se·s diplômé·e·s devant le site de production de gaz de l’entreprise Petrofac sur l’île Chergui, alors que qu’iels réclamaient le respect d’accords passés au lendemain de la révolution concernant des affectations d’emplois[14]. Les deux mouvements se sont entremêlés au fur et à mesure de la progression du conflit ; ils avaient en commun de considérer la participation des entreprises pétrogazières au « développement » de l’île insuffisante au regard des richesses extraites et des nuisances occasionnées. Ces entreprises devaient, selon eux, accorder plus de compensations au territoire de Kerkennah.

This movement occurred at the same time as a sit-in in front of the Petrofac gas production site on the island of Chergui by unemployed graduates calling for the job allocation agreements made in the aftermath of the revolution to be honoured.[14] The two movements became interwoven as the conflict progressed. They shared the view that the oil and gas companies’ contribution to the “development” of the island was inadequate, given the wealth they extracted and the damage they caused. They felt that the firms should give more to the Kerkennah area.

Se mobiliser sur fond de ségrégation régionale – l’usage des relectures de l’histoire et des identités collectives

Taking action in a context background of regional segregation—the use of historical revision and collective identities

Des atteintes à la survie des territoires

Threats to regional survival

Au sein des mobilisations contre les nuisances des industries émergent des revendications qui puisent dans une grammaire de la survie et de la subsistance. Ainsi, la première marche à être organisée à la date du 5 juin à travers Gabès, en 2012, avait pour cri de ralliement « Stop pollution – Je veux vivre » (entretien avec un membre du collectif Stop pollution, octobre 2017) et l’enjeu de la poursuite de la campagne Saker lemsab du printemps 2017 était de pouvoir « respirer un peu d’air pur, vivre », selon son porte-parole(entretien avec le porte-parole de la campagne Saker lemsab, coréalisé avec Irène Carpentier en avril 2018, alors qu’il était candidat aux élections municipales de Gabès avec la liste Attahadi [Le défi]).

The demands that have emerged from the protest movements against industrial hazards draw on the lexicon of survival and subsistence. For example, the rallying cry of the first march organised in Gabès, on 5 June 2012, was “Stop pollution – I want to live” (interview with a member of the Stop Pollution collective, October 2017), and the focus of the continuing Saker lemsab campaign in spring 2017, according to its spokesman, was to be able to “breathe pure air, to live” (interview jointly conducted with Irène Carpentier in April 2018, when he was a candidate in the Gabès municipal elections for the Attahadi [Challenge] group).

« Vivre » peut ici se comprendre au premier degré : échapper aux cancers et autres maladies parfois mortelles imputés à la pollution. Mais le mot recouvre aussi un sens plus large, aux dimensions matérielles et symboliques : celui de mener une vie digne. La rhétorique de la vie digne se rapproche du « cadrage sémantique en termes de dignité » (Ayari, 2011) qui sous-tendait les soulèvements qui ont conduit à la fuite du président Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, le 14 janvier 2011.

“Living” can be understood here in its literal sense: escaping from the cancers and other sometimes fatal conditions attributed to pollution. However, the word also covers a broader meaning, with material and symbolic dimensions: living a life of dignity. The rhetoric of dignity here is connected with the “semantic framing in terms of dignity” (Ayari, 2011) that underpinned the uprisings that led to the departure of President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali on 14 January 2011.

Or, la possibilité de mener une vie digne apparaît conditionnée à l’obtention d’un travail décent, actuellement compromise par l’insuffisance des sources d’emploi dans des territoires spécialisés dans l’industrie[15], ou à la possibilité de continuer à travailler, que ce soit dans l’agriculture, le tourisme ou la pêche, secteurs dont l’essor est compromis par les nuisances industrielles. Ainsi, le dépôt de phosphogypse sur les fonds marins du golfe de Gabès et la disparition des herbiers de posidonie ont entraîné une dégradation des ressources halieutiques (entretien avec un chercheur de l’Institut national des sciences et techniques de la mer, mars 2019) qui s’est répercutée durement sur les revenus des pêcheurs de la région et les a contraints à s’endetter (entretien avec le président du groupement de pêche de Ghannouch, mars 2018). Les pêcheurs à Kerkennah font aussi face à des perturbations de l’écosystème marin et à des baisses de revenus[16], pour lesquelles ils mettent en cause les fuites de pétrole en plus de la généralisation de la pêche au chalut.

However, the possibility of leading a life of dignity seemed conditional on obtaining a decent job, which was currently compromised by the lack of sources of employment in specialist industrial areas,[15] or on the possibility of continuing employment, whether in farming, tourism or fishing, sectors where development was compromised by industrial pollution. Phosphogypsum deposits on the seafloor of the Gulf of Gabès and the disappearance of the posidonia meadows have led to a deterioration in fishery resources (interview with a researcher at the National Institute of Marine Sciences and Technologies, March 2019) which has had a severe impact on the livings of the region’s fishermen and forced them to take on debt (interview with the president of the Ghannouch Fishing Group, March 2018). Those fishing in Kerkennah also experience disruptions to the marine ecosystem and loss of earnings,[16] which they blame on oil leaks as well as the spread of trawl fishing.

Les activités industrielles sont donc contestées pour les atteintes au cadre de vie qu’elles engendrent, mais aussi parce qu’elles mettent en péril la viabilité économique et sociale des territoires dans lesquels elles sont implantées ; « le pétrole ne va pas faire vivre l’île », observe un hôtelier de Kerkennah[17]. Ce constat conduit certains acteur·ice·s associatif·ve·s et syndicaux·ales à mettre en question la cohérence du modèle de développement dans lequel s’inscrit l’activité industrielle sur leur territoire.

Industrial activities are therefore opposed for their impacts on the living environment, but also because they threaten the economic and social viability of the areas where they take place. “Oil will not keep the island alive,” observes one hotelier in Kerkennah.[17] This observation has prompted some civil society and union activists to question the coherence of the development model on which industrial activity in their area is based.

Les mises en récit de la spoliation

Narratives of dispossession

Le combat contre les nuisances industrielles est souvent arrimé à des récits à visée mobilisatrice qui revisitent les trajectoires des territoires en distinguant nettement un avant et un après l’imposition par le haut de l’industrie. Celle-ci joue le rôle d’événement perturbateur, brisant une situation d’équilibre initial sans doute idéalisée[18].

Protest action over industrial hazards is often linked with narratives of mobilisation that draw upon regional history while making sharp distinctions between the time before and after the top-down imposition of industry. In the narrative, the latter plays the role of a disruptive event, one that shattered a doubtless idealised situation of initial equilibrium.[18]

À Gabès, certains acteur·ice·s[19] relisent a posteriori la décision d’y implanter un pôle industriel chimique comme résultat d’une punition qui aurait été infligée à la région en raison du nombre prétendument élevé de partisans de Salah Ben Youssef, leader nationaliste rival du premier président de la Tunisie indépendante, Habib Bourguiba. La région d’origine de ce dernier, le Sahel, aurait, elle, été préservée de la pollution, accueillant des installations touristiques moins nuisibles au cadre de vie[20]. Le dépôt d’un dossier de « région victime » pour la région de Gabès auprès de l’Instance vérité et dignité par des associations, dont la section locale de la Ligue tunisienne des droits de l’homme, fait écho à cette lecture du passé en suggérant une « discrimination intentionnelle de la part de l’État » (Gana, 2019, p. 127). Cette lecture permet de replacer les mouvements contre la pollution dans une histoire de résistance à la domination de l’État central[21] datant de plusieurs dizaines d’années. « Le Sahel ou le Nord, ils vivent avec les fortunes des Suds, que ce soit le pétrole ou bien les mines, ou même les légumes et les fruits, c’est du Sud », déclarait le porte-parole de Saker Lemsab, alors en campagne électorale pour siéger au conseil municipal.

In Gabès, some[19] in hindsight reinterpret the decision to set up an industrial chemical hub in the town as a punishment inflicted on the region because of the purportedly large number of supporters there of Salah Ben Youssef, the nationalist leader who was a rival of the first president of independent Tunisia, Habib Bourguiba. And the story goes that the latter’s home region, the Sahel, was for its part sheltered from pollution, becoming the site of less environmentally burdensome tourist infrastructures.[20] The submission of a “victim region” case on behalf of the region of Gabès to the Truth and Dignity Commission by civil society organisations, including the local section of the Tunisian Human Rights League, echoes this interpretation of the past by suggesting “intentional discrimination on the part of the state” (Gana, 2019, p. 127). This reading re-situates the antipollution movements within a decades-long history of resistance to domination by the central state.[21] “The Sahel or the North, they live off the wealth of the South, whether it be oil or mining, or even vegetables and fruit, it comes from the South,” claimed the spokesperson of the Saker Lemsab campaign during the run-up to the municipal council elections.

Parmi les organisateur·ice·s des mobilisations de Kerkennah contre TPS, la relation à l’État est plutôt présentée comme un rapport de marginalisation de l’archipel, ressentie à travers la faiblesse des services et investissements publics, ou encore le faible contrôle public des pratiques de pêche illégale (entretien avec des membres d’associations et des pêcheurs et habitants de Kerkennah impliqués dans la mobilisation contre TPS, octobre 2018). L’État est décrit simultanément comme « démissionnaire », se limitant à assurer la continuité de la production pétrogazière, soumis aux intérêts étrangers et incapable de montrer un autre visage que celui de la répression, comme lors des mouvements de 2016 ou des poursuites judiciaires d’actions ayant eu lieu en 2017 (entretiens avec plusieurs habitants de Mellita, des pêcheurs d’Ouled Yaneg et de Remla, octobre 2018). Mais c’est une situation de spoliation que dénoncent les acteur·ice·s de la mobilisation contre TPS : « C’est notre terre, c’est nos ressources, et ils ne nous donnent rien. » ; « Ils mangent et nous donnent les os. » (entretien avec un pêcheur d’Ouled Yaneg très actif dans les mobilisations contre TPS et Petrofac, passage où il décrivait les nuisances des activités des compagnies pétrogazières, leurs agissements et les manquements de l’État, octobre 2018). La distinction entre « eux » et « nous » renvoie à une opposition entre celles et ceux qui profitent des ressources présentes sur le territoire – les compagnies étrangères et les acteurs de l’État présentés comme corrompus – et celles et ceux qui n’en profitent pas et à qui ces ressources sont censées revenir, qui subissent, en plus, les nuisances de l’extraction, et se définissent par une appartenance territoriale et sociale à Kerkennah.

Among the organisers of the movements in Kerkennah against TPS, the relations with central government tend to be presented as indicative of the marginalisation of the island group, reflected in the inadequacy of services and public investment, or else poor public oversight of illegal fishing practices (interview with association members, fishermen and inhabitants of Kerkennah involved in the protest movement against TPS, October 2018). At the same time, the state is described as “absent”, content to maintain the continuity of oil and gas production, subject to foreign interests, incapable of expressing itself other than by means of repression, exemplified by the movements of 2016 or the legal proceedings against actions that took place in 2017 (interviews with several inhabitants of Mellita, fishermen from Ouled Yaneg and Remla, October 2018). This is a situation of dispossession that the actors of the movement against TPS condemn: “It’s our land, our resources, and they give us nothing”; “They eat and they throw us the bones” (interview with a fisherman from Ouled Yaneg [Kerkennah] very active in the movements against TPS and Petrofac, when he described the environmental damage caused by the activities of the oil and gas companies, their wrongdoings and the failings of central government, October 2018). The distinction between “them” and “us” points to a contrast between those who benefit from the resources present in the area—the foreign firms and the state actors, presented as corrupt—and those, defined by their territorial and social belonging to Kerkennah, who enjoy none of the benefits that should come to them from those resources but suffer the negative impacts of extraction.

Certain·e·s assurent faire primer une appartenance communautaire au sentiment national, voire, sur le mode de la provocation, se prêtent des velléités indépendantistes[22], ce qui témoigne de doutes quant à leur pleine appartenance à la communauté nationale, issus d’expériences de rejet, du sentiment de ne pas être reconnu·e·s comme des Tunisien·ne·s à part entière.

Some claim to prize membership of their community over national attachment, or even—by way of provocation—hint at a desire for independence,[22] which suggests doubts about being full members of the national community due to experiences of rejection, the sense of not being recognised as fully Tunisian.

« S’il y a un équilibre entre les régions, si tout le monde a les mêmes occasions, si tout le monde a une situation sociale bien, s’il y a un peu de fortune dans chaque gouvernorat, on peut avoir la même Tunisie. On peut avoir cette Tunisie unie », estime un jeune militant de Gabès passé par un parti de gauche reconverti dans la cause de la pollution.

“If there is an equilibrium between the regions, if everyone has the same opportunities, if everyone has a decent social situation, if there is a little bit of wealth in each governorate, we can have the same Tunisia. We can have that united Tunisia,” argues a young activist from Gabès, a former member of a left-wing party converted to the cause of pollution.

La mise en cause de la ségrégation régionale, qui sous-tend les mobilisations, ne se focalise pas uniquement sur une meilleure répartition spatiale des richesses et des nuisances environnementales : elle met aussi en évidence ses dimensions symboliques et morales qui se manifestent par la stigmatisation et ont des implications concrètes.

The complaint about regional segregation that underpins the movements focuses not only on better spatial distribution of wealth and environmental burdens: it also reveals symbolic and moral dimensions, which are revealed through stigmatisation and have real-world implications.

Face au stigmate, l’identité collective est un ressort de la mobilisation

In response to stigmatisation, collective identity is a driver of mobilisation

Les stéréotypes relatifs au Sud résultent d’une construction sociale de l’altérité de la Tunisie sur laquelle reposait le projet politique de Bourguiba, construction sociale ayant néanmoins des racines antérieures. Pour gagner pleinement son indépendance, la Nation devait s’écarter d’un certain état « d’arriération » (Bras, 2004, p. 296) et accéder à la modernité. Or, cette représentation duale entre deux moments du processus de modernisation – le passé dont il s’agissait de se détourner et le futur vers lequel il fallait tendre – s’incarnait territorialement (Bras, 2004). Le Sud était à l’image de « l’autre Tunisie » (Bras, 2004, p. 309) – arriérée, tribale et conservatrice. Et Bourguiba allait lui permettre de progresser considérablement grâce à des politiques volontaristes de développement. On peut considérer que l’opposition nord-sud s’est transmuée en un clivage est-ouest (Belhedi, 2012) qui oppose le littoral ou encore la « Tunisie utile » à la « Tunisie de l’intérieur ». Mais les stéréotypes sur le Sud restent vivaces.

The stereotypes about the South are a result of a social construction of the otherness of Tunisia, which was the basis of Bourguiba’s political project, but has earlier roots. In order to achieve full independence, the nation had to move away from a certain state of “backwardness” (Bras, 2004, p. 296) and embrace modernity. However, this dual representation of two moments in the process of modernisation—the past to be left behind and the future to which to aspire—was territorially embodied (Bras, 2004). The South belonged to the “other Tunisia” (Bras, 2004, p. 309)—backward, tribal, conservative. And Bourguiba would bring it into the modernisation process through aspirational policies of development. It might be said that the opposition between North and South has been transmuted into a division between East and West (Belhedi, 2012), which contrasts the coast or the “useful Tunisia” with the “Tunisia of the interior”. However, stereotypes about the South remain strong.

Des images dépréciatives accolées aux habitant·e·s de Kerkennah ont également été réactivées pendant la séquence protestataire de 2016, afin d’expliquer l’insoumission de la population par ses caractéristiques intrinsèques et de justifier la répression des mouvements, cette dernière ayant constitué le mode de gestion du conflit privilégié par l’État. Ces stéréotypes ont parsemé les entretiens menés lors de l’enquête de terrain : les Kerkennien·ne·s sont présenté·e·s comme des « têtes dures », des « caractères insulaires », « lents à comprendre » par des membres d’agence de l’État qui peinent à trouver l’assentiment des populations pour les projets qu’iels mènent à Kerkennah, voire même par des notables du territoire (entretiens avec des responsables de l’Agence de protection et d’aménagement du littoral et avec le maire de Kerkennah, avril 2019).

During the series of protests in 2016, derogatory images associated with the inhabitants of Kerkennah were also revived to explain the population’s rebelliousness by its intrinsic characteristics and to justify the crushing of the movements, which was the state’s preferred method of conflict management. These stereotypes emerged in the interviews conducted during the field survey: Kerkennians are described as “pigheaded”, “narrow-minded” or “slow-witted” by members of the state agency, who were finding it hard to gain popular assent for their projects in Kerkennah, or even by prominent citizens from the area itself (interviews with officials of the Coastline Protection and Development Agency and with the Mayor of Kerkennah, April 2019).

Face à ces stigmates, les acteur·rice·s des protestations affirment une certaine fierté identitaire, ressort de la mobilisation. IEls prennent le contre-pied de cette image négative en se présentant, par exemple, comme des « révolutionnaires », des « guerriers », des « résistants », puisant dans des mémoires collectives pour se revaloriser collectivement. La volonté de se dresser contre le stigmate revêt une dimension particulière dans les mobilisations contre les nuisances environnementales. Siad Darwish a évoqué l’existence d’une « géographie du propre et du sale » en Tunisie qui est « d’abord une géographie morale » (Darwish, 2018, p. 66, traduction de l’auteure) : la présence de déchets souille les lieux et les gens qui les habitent, traçant des démarcations sociospatiales à forts fondements moraux (Darwish, 2018, p. 66, traduction de l’auteure). Le refus de voir s’installer une décharge dans sa localité tient autant aux impacts qui risquent d’affecter les environs qu’à la souillure morale qui pourrait entacher le quartier et ses habitant·e·s. Lors de la grève générale à El Hamma en opposition à l’annonce de la décision d’implanter les usines de transformation chimique et le terril destiné à stocker les déchets de phosphogypse à Menzel El Habib, les slogans mobilisateurs étaient focalisés sur ce dernier équipement. « Non au phosphogypse ! », « Menzel El Habib n’est pas une poubelle ! », clamaient les pancartes. C’est le rejet de l’identification du territoire à une décharge, en accueillant des déchets que la localité d’Oudhref avait refusés quelques années auparavant, qui était mis en avant dans le cortège, plus que les risques sanitaires et environnementaux liés aux rejets et la pression sur les ressources en eau. En outre, les discours prononcés devant la foule remobilisaient l’identité tribale, en se référant au courage des Beni Zid, comme un emblème, une « ressource mobilisable pour l’affirmation d’une identité de groupe » (Camau, 2018, p. 214).

In response to these stereotypes, the protesters express a certain pride in their identity as a source of mobilisation. They counter the insults by presenting themselves, for example, as “revolutionaries”, as “warriors”, as “resistance fighters”, drawing on collective memory to reclaim collective value. The desire to oppose the stigma takes on a particular dimension in the movements against environmental hazards. Siad Darwish has written of a “moral geography of waste” in Tunisia, whereby places are labelled as dirty or clean: the presence of waste sullies places and the people who live in them, outlining sociospatial differences with strong moral foundations (Darwish, 2018, p. 66). The refusal to have a landfill site nearby arises both from its physical impact on its surroundings and from the moral taint that it might leave on the neighbourhood and its inhabitants. During the general strike in El Hamma in response to the announcement of the decision to locate the chemical processing plants and the slag heap for storing the phosphogypsum waste in Menzel El Habib, the protest slogans focused on the second of these entities. “No to phosphogypsum!”, “Menzel El Habib is not a garbage pile!” proclaimed the banners. The march signalled a rejection of the territory being identified with a garbage tip by accepting waste refused by the district of Oudhref a few years earlier, rather than the health and environmental risks associated with the waste and the pressure on water resources. In addition, the speeches to the crowd emphasised tribal identity, referring to the courage of the Beni Zid as an emblem, a “resource that can be mobilised to assert group identity” (Camau, 2018, p. 214).

Des revendications oscillant entre demandes d’arrêt des nuisances et exigences de compensations

Fluctuation between demands for an end to the hazards and for compensation

Deux ensembles de revendications cohabitent au sein des mobilisations relatives aux nuisances industrielles et dont l’ancrage local est fort : d’une part, des demandes d’arrêt des nuisances environnementales et sanitaires des activités industrielles, voire, plus rarement, d’arrêt des activités elles-mêmes ; et, d’autre part, des demandes de compensations – création d’emplois, compensations financières ou matérielles, etc. D’un côté, on exprime la volonté de mettre fin à une situation néfaste ; de l’autre, on prend acte de cette situation et l’enjeu est d’obtenir une contrepartie.

Two types of claims coexist within the movements against industrial hazards, with strong local roots: first, demands for an end to the environmental and health hazards caused by the industrial activities, or more rarely an end to the activities themselves; and second, demands for compensation—job creation, financial or material compensation, etc. In the first case, what is sought is the cessation of harm; in the second, the harm is accepted and the objective is to get something in return.

Des associations et collectifs militants, qui mettent l’accent sur un besoin de transition du territoire vers d’autres orientations économiques, ont tendance à disqualifier le caractère intéressé de démarches visant à obtenir des miettes du gâteau. Mais la cohabitation de ces deux ensembles de revendications au sein de mêmes groupes de mobilisation peut se comprendre si on prête attention aux conditions matérielles de subsistance, aux pratiques économiques et aux attentes en matière de justice des acteurs locaux, à la manière des approches des économies morales (Thompson, 1971 ; Scott, 1976 ; Fassin, 2009 ; Siméant, 2010 ; Allal, Catusse et Emperador Badimon, 2018). Les communautés de Gabès et Kerkennah sont confrontées à des nuisances industrielles, à des taux de chômage élevés et aux baisses de revenus de l’agriculture et de la pêche qui peuvent s’apparenter à des « crises de subsistance » (Scott, 1976, p. 17). Ces communautés y opposent la revendication de droits moraux, en premier lieu, un droit à la survie. Par ailleurs, elles se trouvent enchevêtrées dans des relations de dépendance avec les industries responsables des nuisances du fait de la rareté des alternatives économiques locales. Ces industries fournissent en effet des emplois, des services, un approvisionnement des fonds de développement et distribuent des compensations individuelles en contrepartie des pollutions. Les mobilisations reprennent à leur compte les promesses d’un « paternalisme d’État » (Camau, 2018, p. 228-230) sur lequel reposent les attentes des acteur·ice·s et qui fondent leurs revendications. Elles surviennent souvent quand les accords sont rompus, quand des accidents mettent en danger le fragile équilibre de subsistance ou quand la distribution des compensations semble injuste au regard d’un ordre moral.

Civil society organisations and activist groups, which focus the area’s necessary transition to other economic activities, tend to disregard the self-interested aspect of approaches in which the aim is to obtain some crumbs from the cake. However, the coexistence of these two types of demand within the same activist groups is understandable if one considers the material conditions of survival, the economic practices and hopes for justice of local actors, from the perspective of moral economy-based approaches (Thompson, 1971; Scott, 1976; Fassin, 2009; Siméant, 2010; Allal, Catusse and Emperador Badimon, 2018). The communities of Gabès and Kerkennah face industrial hazards, high levels of unemployment and falling revenues from farming and fishing, problems akin to “subsistence crises” (Scott, 1976, p. 17). In response, they claim moral rights, starting with the right to survival. Moreover, they are entangled in dependency relations with the industries responsible for the hazards because of the scarcity of alternative local sources of jobs and services, with the capacity to bring development funds and to distribute individual compensation to set against the pollution. The movements internalise the promises of a “state paternalism” (Camau, 2018, p. 228-230) on which the expectations of the actors depend and which forms the basis of their claims. They often arise when agreements are broken, when accidents threaten the fragile balance of subsistence or when the distribution of compensation seems unfair with respect to a moral order.

Ainsi, à Bouchemma, en mai 2017, la fuite de gaz émanant d’installations du groupe chimique tunisien peut être vue comme l’incident de trop qui a poussé les habitant·e·s à sortir dans la rue et à réclamer des compensations pour les récoltes brûlées, de meilleurs hôpitaux et des emplois pour les jeunes chômeur·se·s, y compris auprès d’autres entreprises présentes dans la zone industrielle, au nom d’une notion partagée du droit et de la justice. Un des initiateurs du sit-in devant l’entreprise OMV explique ainsi : « Les gens prennent un grand coup de pollution, mais ils sont pressés par le chômage, la pauvreté. Il faut un équilibre social qui nous donne le droit de vivre comme il faut. On peut vivre dans la pollution, mais à condition de gagner bien, de faire un bon week-end de temps en temps. Les gens ne sont pas contre que Bouchemma accueille les gaz, mais veulent que les entreprises assument leur responsabilité sociale. » Cet extrait d’entretien (avril 2018) montre la place qu’occupe le registre moral dans la mobilisation, mais il suggère aussi que celle-ci peut se déclencher moins pour restaurer un ordre ancien que par effet d’opportunité et à la suite des initiatives d’acteurs qui y voient un « art du possible » (Fioroni, 2018, p. 162).

For example, in Bouchemma in May 2017, the gas leak from the Tunisian Chemicals Group may be seen as the final straw that prompted the inhabitants take to the streets and call for compensation for the burnt harvests, for better hospitals and jobs for unemployed youngsters, including from other companies in the industrial zone, in the name of a shared conception of law and justice. One of the initiators of the sit-in at OMV explains it as follows: “People catch a big dose of pollution, but they are ground down by unemployment, by poverty. There needs to be a social equilibrium that gives us the right to live decently. You can live in polluted conditions, but only if you earn a decent wage, can enjoy a good weekend from time to time. People are not against the gas coming to Bouchemma, but they want the companies to accept their social responsibility.” This interview (April 2018) extract shows the role of the moral register in the protest movement, but it also suggests that this movement may be instigated less to restore an old order than to grasp an opportunity and in the wake of initiatives taken by people who see it as an “art of the possible” (Fioroni, 2018, p. 162).

L’exacerbation de conflits au niveau microlocal

The exacerbation of conflicts at micro-local level

Appartenances communautaires et trames conflictuelles du territoire

Community belonging and territorial networks of conflict

Si les identités collectives, par leur pouvoir fédérateur, constituent des assises pour les mobilisations contre les nuisances environnementales (et en sont aussi, par certains aspects, des produits), elles peuvent tout aussi bien contribuer à la fragmentation de la dynamique de mobilisations, suscitant ou réactivant des tensions, des conflits aux multiples ressorts qui (re)produisent des figures d’altérité à un niveau microlocal. On voit se dégager ce qu’on pourrait nommer des « trames conflictuelles du territoire » (Beuret et Cadoret, 2014, p. 223) : des conflits et tensions chroniques qui affectent et sont réactivés par ces mobilisations.

While collective identities, because of their unifying power, provide foundations for movements of protest against environmental hazards (and are also, in certain respects, produced by them), they can also contribute to the breakdown of protest dynamics, triggering or reactivating tensions and conflicts of multiple kinds that (re)produce instances of otherness at a microlocal level. One sees the emergence of what could be called “territorial networks of conflict” (Beuret and Cadoret, 2014, p. 223): chronic conflicts and tensions that affect and are reactivated by these movements.

À Gabès, les tensions entre des groupes fluctuants, issus d’un côté des quartiers de Menzel et de Chenini et de l’autre de Jara et de Chott Salem, ont remobilisé d’anciennes rivalités, liées à des conflits autour de l’approvisionnement en eau des oasis, mais aussi à la conquête coloniale française (Kraiem, 1988). Ainsi, Menzel et Chenini auraient résisté héroïquement alors que Jara et Chott Salem auraient pactisé avec le colon. Mais les tensions entre ces deux groupes sont également alimentées par des ancrages politiques et des bases sociologiques différents[23]. Ces luttes d’influence ont été exacerbées par le recours des acteur·ice·s locaux à l’insertion dans des réseaux et des initiatives nationaux et transnationaux qui visaient à médiatiser le problème de la pollution et faire pression pour que des actions soient mises en œuvre, mais aussi à améliorer leur propre position dans les rapports de forces locaux.

In Gabès, the tensions between shifting groups originating, on the one hand, from the districts of Menzel and Chenini and on the other from Jara and Chott Salem, revived old rivalries linked with conflicts around the water supplied to the oases but also with the French colonial conquest (Kraiem, 1988), which Menzel-Chenini reportedly resisted heroically whereas Jara-Chott Salem purportedly made peace with the colonists. However, the tensions between these two groups are also fed by different political roots and sociological foundations.[23] These struggles of influence have been exacerbated by the incorporation of the local actors into national and transnational networks and initiatives intended to generate media coverage of the problem of pollution and apply pressure for action, but also to improve their position in local power relations.

Au plus fort du conflit social de 2016 à Kerkennah, les participant·e·s à un sit-in postés devant le site de production gazière de Petrofac sur l’île Chergui, revendiquant le respect d’accords préalables portant sur des créations d’emplois, se sont déplacé·e·s vers Mellita, comptant ainsi sur la « protection » des habitant·e·s et leur ardeur face à la police (entretiens avec un des organisateurs du sit-in pour l’emploi et avec des habitant·e·s de Mellita, octobre 2018). Suite à des discussions avec les protestataires de Mellita, et notamment avec un groupe engagé dans le mouvement contre TPS, ils ont convenu d’intégrer les demandes de contribution au développement en plus de la régularisation des emplois des chômeur·se·s à leurs revendications. Or, si l’accord signé en septembre 2016 entre les représentants des contestataires, des autorités nationales et des sociétés pétrolières a acté la régularisation des emplois des chômeur·se·s, les réalisations ont été faibles concernant les retombées en matière de « développement ». Ceci est à l’origine d’une certaine rancœur à Mellita envers le groupe des diplômé·e·s chômeur·se·s et qui réactive un ressentiment envers Remla, qui concentre les services et les administrations (entretiens avec des habitants de Mellita investis dans le mouvement contre les entreprises pétrogazières, octobre 2018). Inversement, les habitant·e·s de Mellita sont mis en cause pour la pratique de la pêche illégale au chalut et les blocages récurrents de l’accès au bac de Sidi Youssef : « ils nous prennent en otage » (entretien avec un responsable associatif de Kraten, mars 2018).

At the height of the social conflict in Kerkennah in 2016, the people holding the sit-in at the Petrofac gas production site on Chergui Island demanding that it meet its previous undertakings on job creation, moved to Mellita, counting on the “protection” of the inhabitants of Mellita and their readiness to face down the police (interviews with one of the organisers of the sit-in for jobs and with the inhabitants of Mellita, October 2018). Following discussions with the protesters in Mellita, and in particular with a group involved in the movement against TPS, they agreed to include demands for contributions to development in addition on top of the call for regularisation of the situation on jobs for the unemployed. However, while the agreement signed in September 2016 between the protesters’ representatives, the national authorities and the oil companies implemented job regularisation for the unemployed, not much was achieved regarding the “development” outcomes. This explains a certain bitterness in Mellita towards the group of unemployed graduates, which has reactivated resentment towards Remla, where many government departments are located (interviews with inhabitants of Mellita involved in the movement against the oil and gas companies, October 2018). Conversely, the inhabitants of Mellita are blamed for illegal trawler fishing and recurrent blockades that prevent access to the Sidi Youssef ferry. “They use us as hostages” (interview with an official in a civil society organisation in Kraten, March 2018).

Réponses aux mobilisations : évitements, déplacements, « achat » de paix sociale

Response to the protest movements: avoidance, displacement, “buying” of social peace

Ces rivalités peuvent être attisées par les mesures de gestion de crise mises en place par les pouvoirs publics. Celles-ci oscillent entre ajustements décidés dans l’urgence, mais qui ont tendance à durer – sociétés d’environnement ou de développement, distribution plus intense de compensations au nom de la responsabilité sociétale des entreprises (RSE), déviation des routes empruntées par les camions d’hydrocarbures, etc. – et projets d’ampleur qui peinent à se concrétiser (délocalisation des unités industrielles).

These rivalries may be stirred up by the crisis management measures put in place by the authorities. Such measures range from short-term emergency adjustments that then become permanent—environmental development firms, increased compensation within a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) framework, diversions to the routes used by hydrocarbon trucks, etc.—to substantial projects that are never implemented (relocation of industrial units).

Dans la région de Gabès, c’est le démantèlement des unités gabésiennes du GCT et leur transfert à Menzel El Habib qui sont présentés par les autorités comme la réponse principale aux mécontentements liés aux nuisances environnementales. Le projet, qui suscite l’opposition d’habitant·e·s d’El Hamma et de Menzel El Habib (même si d’autres, entrevoyant des créations d’emplois et des rachats de terres dans cette zone rurale délaissée, accueillent le projet favorablement), prend du retard. Or, l’État s’était engagé à mettre fin au déversement de phosphogypse à Chott Salem le 30 juin 2017. Face aux réclamations des habitant·e·s de Chott Salem qui souhaiteraient retrouver un cadre de vie décent et reprochent aux pouvoirs publics leurs promesses non tenues, ceux-ci en imputent la responsabilité aux protestataires d’El Hamma et Menzel El Habib (et auparavant à ceux d’Oudhref), ce qui exacerbe les tensions entre les communautés de Chott Salem et celles d’El Hamma et Menzel El Habib (entretiens avec des membres d’une association de Chott Salem, mars 2018).

In the Gabès region, it is the dismantling of GCT’s units in Gabès and their transfer to Menzel El Habib that the authorities present as the main response to discontent linked with environmental pollution. The project, which has met with opposition from the inhabitants of El Hamma and Menzel El Habib (although others, hopeful of new jobs and land purchases in this neglected rural area, have welcomed the project) has fallen behind. The government had undertaken to end the discharge of phosphogypsum in Chott Salem on 30 June 2017. In response to the demands of the inhabitants of Chott Salem, who want to return to decent living conditions and blame the authorities for not keeping their promises, the latter attribute the responsibility to the protesters in El Hamma and Menzel El Habib (and previously in Oudhref), thereby heightening tensions between the communities of Chott Salem and of El Hamma and Menzel El Habib (interviews with members of a civil society organisation in Chott Salem, March 2018).

À Kerkennah, depuis 2016, le trajet initial des camions de condensat (un gaz inflammable) de Petrofac a été dévié. Ils empruntaient auparavant la route principale de l’île pour rejoindre le port de Sidi Youssef et traversaient le village de Mellita. Depuis le conflit, ils sont chargés sur des bateaux qui les acheminent à Sfax au niveau de l’embarcadère de la zone touristique de Sidi Fredj, aménagé à cette fin, au grand dam des hôteliers (entretiens avec des gérants hôtels de Sidi Fredj, octobre, avril et mai 2018). Cela permet à l’entreprise de réduire le risque de blocages par les mouvements protestataires.

In Kerkennah, since 2016, the trucks carrying Petrofac’s condensate (an inflammable gas) have been diverted from their original route. In the past, they used the island’s main road to reach the port of Sidi Youssef, passing through the village of Mellita. Since the conflict, they have been loaded onto boats that carry them to Sfax, where the landing stage for the tourist area of Sidi Fredj has been adapted for this purpose, to the great annoyance of the hoteliers (interviews with hotel managers in Sidi Fredj, October, April and May 2018). In this way, the company is able to reduce the risk of blockades mounted by the protest movements.

Ces délocalisations, réaménagements et déplacements dessinent une nouvelle cartographie de la distribution des nuisances : les installations sont transférées dans des zones où le rapport de forces est considéré (à tort ou à raison) comme plus favorable à la poursuite des activités industrielles, sans que celles-ci ne soient entravées par des blocages. Cela amène des habitant·e·s de ces zones à déplorer de nouvelles injustices entre localités au niveau régional.

These relocations, adaptations and displacements have redrawn the distribution map of environmental hazards: facilities are transferred to areas where the power balance is considered (wrongly or rightly) more favourable to the continuation of industrial activities without hindrance from roadblocks. The result is that the people living in these areas complain about new injustices between localities at regional level.