I. Introduction

I. Introduction

Dans notre village d’étude au Sud-Liban, nous travaillons sur la relation entre la propriété de la terre et son exploitation sur une longue durée. Les villageois parlent fièrement de la façon dont ils ont réclamé des « droits » à leurs propriétaires. Qu’il s’agisse de terrains à bâtir ou d’exploitation de la terre, ils l’expriment par le terme de haqq, équivalent de droits au sens particulier et de justice au sens abstrait. Parfois, ils évoquent une telle action dans l’abstrait, mutalabat bi-ʾl- haqq, et demandent des droits/la justice à travers la lutte et le mouvement social. En pratique, leurs contestations leur permettent d’atteindre certains de leurs objectifs, mais pas tous. Aussi, en lien avec la thématique de ce numéro, nous nous sommes demandé dans quelle mesure leurs revendications pouvaient de manière pertinente être conçues comme exprimant quelque chose de plus large : une sorte de « droit au village » dans l’esprit du slogan de Lefebvre si célébré - « le droit à la ville » -, alors même que les villageois n’interprètent pas leurs actions sous une telle abstraction globale.

In the village of South Lebanon where we have been working on documenting the long-term relation between land-tenure and land-use, villagers speak proudly of how they claimed their ‘rights’ from landlords. In the case of both house plots and the cultivation of land, they express this in terms of haqq, the equivalent of ‘right’ in the particular and of justice in the abstract. On occasion they speak of such action in the abstract, mutalabat bi-ʾl- haqq, demanding rights/justice through struggle and social movement. In practice, their contestations achieved some of their ends but not all. And so, in line with the theme of this issue, we thought to ask whether their claims to rights could be fruitfully conceived as expressing something broader: a kind of ‘Right to the Village’, in the spirit of Lefebvre’s much-feted slogan, the ‘Right to the City’- although the villagers did not interpret their actions through any such global abstraction.

Voici le plan de notre étude : nous considérons d’abord ce que serait un « droit au village » fidèle à la propre formulation de Lefebvre. Nous en notons alors les limites et proposons des modifications. Cet exercice reste avant tout abstrait. Nous tournant alors vers les deux conflits analysés dans notre village d’étude, nous considérons à travers l’espace et le temps ce qui a pu être obtenu au niveau de ce village, Sinay au Sud-Liban. Depuis au moins la fin du XIXe siècle, les terres de Sinay sont possédées par des personnes extérieures au village. Cette histoire montre le succès partiel rencontré par une revendication de droits au sein des dynamiques régionales et internationales de reproduction de l’ordre propriétaire dominant. Notre article étudie et éclaire le traitement du monde rural par Lefebvre au sein d’une théorie urbaine. Et il suggère la difficulté pour les acteurs de traduire des droits particuliers dans la revendication globale et durable d’un « Droit au Village ».

The structure of our inquiry is as follows: we first consider what could be a ‘Right to the Village’ faithful to Lefebvre’s own formulation. We note the limitations in his formulation and propose modifications. This exercise remains an abstract one. Turning then to the two contestations from our village of study, we consider in space and time what proved achievable at the level of the village of Sinay in South Lebanon. Since at least the late 19th century, the lands of Sinay have been owned by persons from outside the village. This history exposes the partial success of a claim for rights within the evolving regional and international reproduction of the governing property order. It examines and highlights Lefebvre’s treatment of the rural world through an urban theory. And it suggests the difficulty for actors of translating particular rights into a global and lasting claim to a ‘Right to the Village’.

Lefebvre et un « Droit au Village »

Lefebvre and a ‘Right to the Village’

Le droit à la ville d’Henri Lefebvre (écrit en 1967 et publié en mars 1968) était un manifeste pour que le prolétariat reprenne la ville depuis les marges où il avait été relégué, depuis les bidonvilles et banlieues périphériques, comme un moyen de refaire « la vie urbaine » (Lefebvre, 2009, p. 108). Lefebvre distinguait trois éléments dans ce « droit » : d’abord, le droit à l’appropriation – à la fois un droit pratique d’usage, d’occuper et d’accéder aux espaces de la ville, mais aussi un concept philosophique – ; ensuite, le droit d’habiter ; et enfin, le droit de participer à toutes les décisions qui produisent les espaces de la ville. L’appropriation donne aux habitants le droit à un « usage plein et entier » de l’espace urbain au quotidien, et l’espace doit être produit de manière à rendre possible cet « usage plein et entier » (Purcell, 2002). Le droit d’habiter « implique un droit au logement : un lieu où dormir, (…) un lieu où se détendre, un lieu d’où partir à l’aventure » (Mitchell, 2003, p. 19). Lefebvre insiste sur la différence entre un droit d’habiter et des droits de propriété. Le droit à la participation inclut le droit des habitants à jouer un rôle dans la modification de leur espace (Purcell, 2002).

Henri Lefebvre’s Le droit à la ville (written in 1967 and published in March 1968) was a manifesto for the proletariat to retake the city from where it had been banished to the edges, the peripheral slums or suburbs, as part of remaking ‘la vie urbaine’ [urban life] (Lefebvre, 2009, p. 108). At times, Lefebvre distinguished three elements in this ‘right’: first, the right to appropriation – both a practical right to use, to occupy and to access the city’s spaces, but also a philosophical concept ; second, the right to habitation; and third, the right to participation in all decisions that produce the spaces of the city. Appropriation gives inhabitants the right to ‘full and complete usage’ of urban space in the course of everyday life; space must be produced in a way that makes that ‘full and complete usage’ possible (Purcell, 2002). The right to inhabit “implies a right to housing: a place to sleep, […] a place to relax, a place from which to venture forth” (Mitchell, 2003, p. 19). Lefebvre insists on the differentiation between a right to inhabit and property rights. The right to participation includes the right of inhabitants to play a role in the modification of their space (Purcell, 2002).

Pour Lefebvre, le Droit à la Ville est non seulement un droit à la socialité et à la vie urbaines, mais aussi un droit d’user et accéder aux ressources de l’environnement urbain, ce qui inclut des ressources sociales, politiques et matérielles (Harvey, 2008; Lefebvre, 2009; Mitchell, 2003). Lefebvre définit le Droit à la Ville comme le droit « à la vie urbaine, à la centralité rénovée,aux lieux de rencontres et d’échanges, aux rythmes de vie et emplois du temps permettant l’usage plein et entier de ces moments et lieux » (Lefebvre 2009, p. 133). Le concept de Droit à la Ville a nourri le débat sur l’espace urbain et soulevé des questions concernant l’espace public et l’exclusion sociale (Mitchell, 2003), la citoyenneté (Amin et Thrift, 2002), le logement (Weinstein et Ren, 2009) et la gouvernance urbaine au temps du néolibéralisme (Harvey, 2012, 2008). De tels débats ne sont pas cantonnés aux pays occidentaux mais se sont aussi développés dans les pays du Sud, comme l’Inde (Bhan, 2009), le Brésil (Budds et Teixeira, 2005), l’Afrique du Sud (Parnell et Pierterse, 2010) et le Liban (Fawaz, 2009).

For Lefebvre, the Right to the City is not only a right to sociality and urban life, but also a right to use and access urban environmental resources, including social, political and material resources (Harvey, 2008; Lefebvre, 2009; Mitchell, 2003). Lefebvre defines the Right to the City as the right “to urban life, to renewed centrality, to places of encounter and exchange, to life rhythms and time uses, enabling the full and complete usage of…moments and places…” (Lefebvre, 1996, p. 179). The concept of the Right to the City has stimulated much debate about urban space and raised questions concerning public space and social exclusion (Mitchell, 2003), citizenship (Amin and Thrift, 2002), housing (Weinstein and Ren, 2009), and urban governance under neoliberalism (Harvey, 2012, 2008). Such debates are not limited to Western countries but have been developed in countries of the South, such as India (Bhan, 2009), Brazil (Budds and Teixeira, 2005), South Africa (Parnell and Pieterse, 2010) and Lebanon (Fawaz, 2009).

Lefebvre regardait le capital industriel comme ayant créé un urbainpresque universel, d’où le fait que son slogan d’un « Droit à la Ville » apparaisse comme une sorte de révolution globale :

Lefebvre regarded industrial capital as having created an almost universal urbain, thus his slogan of a ‘Right to the City’ appears as a sort of global revolution:

Ceci appelle à côté de la révolution économique (planification orientée vers les besoins sociaux) et de la révolution politique (contrôle démocratique de l’appareil d’Etat, autogestion généralisée) une révolution culturelle permanente. Il n’y a pas d’incompatibilité entre ces niveaux de la révolution totale, pas plus qu’entre la stratégie urbaine (réforme révolutionnaire visant la réalisation de la société urbaine sur la base d’une industrialisation avancée et planifiée) et la stratégie visant la transformation de la vie paysanne traditionnelle par l’industrialisation. Bien plus : dans la plupart des pays, aujourd’hui, la réalisation de la société urbaine passe par la réforme agraire et l’industrialisation. Qu’un front mondial soit possible, cela ne fait aucun doute. Qu’il soit impossible aujourd’hui, c’est certain. Cette utopie, ici comme souvent, projette sur l’horizon un « possible-impossible » (Lefebvre, 2009, p.135).

This calls for, apart from the economic and political revolution (planning oriented towards social needs and democratic control of the State and self-management), a permanent cultural revolution. There is no incompatibility between these levels of total revolution, no more than between urban strategy (revolutionary reform aiming at the realization of urban society on the basis of an advanced and planned industrialization) and strategy aiming at the transformation of traditional peasant life by industrialization. Moreover in most countries today the realization of urban society goes through the agrarian [re]form[1] and industrialization. There is no doubt that a world front is possible, and equally that it is impossible today. This utopia projects as it often does on the horizon a ‘possible-impossible’ (Lefebvre, 1996, pp. 180–181).

Abordant les changements en France dans les années 1950 et 1960, Lefebvre nota l’interaction et l’interrelation entre le rural et l’urbain, et la transformation de la campagne. La ville selon les mots de Lefebvre est une « œuvre » ; elle est le résultat d’une production de l’espace et la production de socialité dans la ville. « La ville en expansion attaque la campagne, la corrode, la dissout. (…) La vie urbaine pénètre la vie paysanne en dépossédant d’éléments traditionnels : artisanat, petits centres qui dépérissent au profit des centres urbains (commerciaux et industriels, réseaux de distribution, centres de décision, etc.). Les villages se ruralisent en perdant la spécificité paysanne » (Lefebvre, 2009, p. 66-67).

Addressing the changes in France in the 1950-60s, Lefebvre notes the interaction and interrelation between the rural and the urban, and the transformation of the countryside. The city in Lefebvre’s words is an “oeuvre” (a making); it is the result of a production of space and the production of sociality in the city. He argues: “the expanding city attacks the countryside, corrodes and dissolves it. Urban life penetrates peasant life, dispossessing it of its traditional features: crafts, small centres which declined to the benefit of urban centres (commercial, industrial, distribution networks, centres of decision-making, etc.). Villages become ruralized by losing their peasant specificity” (Lefebvre, 1996, p. 119).

Certes, on pourrait dire que Lefebvre perçoit déjà l’urbain et l’industrialisation comme incorporant le village. Ainsi, les droits à l’espace dans un village seraient les mêmes que dans une ville, les travailleurs y habitant ayant des droits au logement, aux valeurs d’usage nécessaire au travail, et à gouverner l’espace, mais cela se ferait dans un espace de moindre concentration de population qu’une ville. Est-ce réellement satisfaisant cependant ? N’y a-t-il rien de spécifique à la nature de cet espace ainsi revendiqué ou à la nature de l’œuvre dans un village par rapport à une ville ?

Indeed, the argument could be made that Lefebvre foresaw the urban and industrialisation as fundamentally subsuming the village. So, rights to space in a village would be the same as in a city, working class inhabitants having rights to housing, to the use-values needed for work, and to governing of the space, simply in a space of smaller population concentration to the city. But is this really satisfactory? Is there nothing that is specific to the nature of the space being so claimed or to the nature of the oeuvre in a village as opposed to a city?

La crise rurale est selon Lefebvre le résultat de l’expansion de la « fabrique urbaine » suivant « la maîtrise complète sur la nature » dans les aires rurales et donc la perte de « la vie paysanne traditionnelle » (voir le chapitre 9 dans Lefebvre, 2009). Ces deux expressions, la maitrise de la nature et la vie paysanne traditionnelle, ne nous aident pourtant pas. Il faudrait prendre en compte l’insistance de Lefebvre sur la fabrique (l’œuvre) plutôt que cette référence impromptue à la domination de la nature. Ainsi, d’une façon que « l’urbain » ne nous autorise pas à théoriser, concevoir « le village » implique nécessairement qu’une partie de l’œuvre dans un tel espace est la transformation de la nature en espace productif. En d’autres termes, si l’on veut redéployer le droit à la ville de Lefebvre vers un droit au village qui lui soit parallèle mais distinct, on doit traiter la « nature » non comme un objet (maîtrise de la nature) mais comme une composante du travail de l’homme (œuvre) pour produire de la nourriture et d’autres objets. Il faut aussi être précis concernant les conditions qu’implique la « réforme agraire » à laquelle fait référence Lefebvre. Dans son raisonnement, il considère les réformes agraires comme faisant partie d’un ensemble plus large de réformes (Merrifield, 2006). Cela implique que si les villageois sont capables d’exercer leurs droits sur l’espace du village, ils doivent posséder la terre, ou du moins bénéficier de droits très stables sur elle comme par exemple lorsque la terre est formellement possédée par l’Etat. Plus largement, que cela soit en regard du droit à la ville ou d’un droit au village, Lefebvre évoque la participation politique, mais sans réellement spécifier les institutions qui gouvernent l’attribution d’un droit et sa reconnaissance légale, ni comment, par la participation, des acteurs jusque-là exclus pourraient forcer cette reconnaissance. Dans le cas du village, le problème de l’auto-gestion est essentiel : dans quelle mesure les formes existantes de gouvernement municipal ont-elles légalement le pouvoir de jouer un tel rôle ? Si ce n’est pas le cas, d’autres formes de mobilisation sociale sont-elles requises pour transformer les formes existantes de gouvernement ? Enfin, alors que « le droit à la ville » suppose que le pouvoir supérieur est en fin de compte celui de l’Etat (la ville de Paris étant sans aucun doute le modèle de Lefebvre), comment une société villageoise peut s’adresser directement à « l’Etat » demeure moins évident.

The rural crisis according to Lefebvre is the result of the expansion of ‘urban fabric’ following la maîtrise complète sur la nature [complete control over nature] in rural areas and thus the loss of la vie paysanne traditionelle [traditional peasant life] (cf. chapter 9 in Lefebvre, 2009). These two terms, la maitrise de la nature and la vie paysanne traditionelleare not helpful. One would need to take into account Lefebvre’s emphasis on making [‘œuvre’] rather than his off-hand reference to domination of nature. Thus, in a manner that ‘the urban’ does not allow us to theorize, conceiving of ‘the village’ necessarily means that one part of the oeuvre in such a space is the making of nature into a productive space. In other words, if we wish to redeploy Lefebvre’s droit à la ville towards a parallel but distinct droit au village, we must treat ‘nature’ not as an object (maitrise de la nature) but as a party in the human work (œuvre) of making food and other objects. We need also to be precise concerning the conditions alluded to by Lefebvre’s reference to ‘réforme agraire’ [land reform]. In his reasoning, Lefebvre considers agrarian reforms as part of an ensemble of reforms (Merrifield, 2006). This implies that if villagers are to be able to exercise rights to the space of the village, they must own the land, or at least enjoy very stable rights to it, as for example, if land is formally owned by the state. More widely, be it with regard to the droit à la ville or a droit au village, Lefebvre evokes political participation but with no real specification of the governing institutions that can award or recognize a right in law and how actors previously excluded may force that recognition. In the case of the village, the problem of auto-gestion [self-management] is important: to what extent are existing forms of municipal government legally empowered to play such a role? Or are other forms of social mobilisation required to transform those existing forms of government? And lastly, while the ‘droit à la ville’ supposes that the power called upon is ultimately that of the state (the city of Paris doubtless being Lefebvre’s model), how village society can address ‘the state’ directly may be less evident.

Considérons maintenant des moments historiquement bornés, au cours desquels une revendication s’est faite contre un pouvoir organisé. Ci-après, après rapide description du village, nous rendons brièvement compte de deux aspects : une revendication pour continuer à cultiver la terre, et une autre pour en obtenir afin de construire des maisons.

Let us now consider particular historical moments when a claim against organized power was actualized. Below, after a short description of the village, we consider two short accounts, the first concerning a claim to continue to cultivate land and the second to obtain land for building homes.

II. Sinay : une étude de dynamiques rurales

II. Sinay: study in rural changes

Jabal ‘Amil est le nom historique de l’extension sud du Mont Liban, qui couvre une aire d’environ 2000 km² depuis la rivière al-Awwali jusqu’au nord de la Palestine. Après la création de l’Etat libanais en 1920, quand nombre de villages furent annexés à la Palestine, Jabal ‘Amil est devenu le Sud-Liban (Bazzi, 2002). Au XIXe siècle, Jabal ‘Amil était une zone de passage commercial reliant le cœur de la Syrie aux autres parties de l’empire ottoman. Cependant, avec le développement du port de Beyrouth et celui de la ligne de chemin de fer Beyrouth-Damas, Jabal ‘Amil a perdu de son importance commerciale. Son rôle économique et politique a diminué tandis que le Mont Liban se développait (Mervin, 2000). Surtout rural au début du XXe siècle, le paysage de Jabal ‘Amil changea avec son intégration au marché mondial (Bazzi, 2002 ; Mervin, 2000). Les plantations de tabac, les migrations, les changements économiques, et la situation géopolitique du Jabal ‘Amil en relation avec la Palestine, l’occupation sioniste puis la construction de l’Etat israélien, ont transformé la région (Jaber, 1999).

Jabal ‘Amil is the historical name of the southern extension of Mount Lebanon, extending over an area of around 2,000sq km from al-Awwali River to northern Palestine. After the creation of the Lebanese state in 1920, when a number of villages were annexed to Palestine, Jabal ‘Amil became known as South Lebanon (Bazzi, 2002). In the 19th century, Jabal ‘Amil was a zone of commercial passage linking the Syrian mainland to other parts of the Ottoman Empire. However as Beirut’s harbour grew and the Beirut-Damascus railway developed, Jabal ‘Amil lost its commercial importance. Its economic and political role decreased while Mount Lebanon developed (Mervin, 2000). Predominantly rural in the early 20th century, Jabal ‘Amil’s landscape changed with its integration in the global market (Bazzi, 2002; Mervin, 2000). Tobacco plantation, migration, economic changes, and the geo-political location of Jabal ‘Amil in relation to Palestine and the Zionist occupation and state-building, mark the transformation of the area (Jaber, 1999).

Au Liban aujourd’hui, le rural et l’urbain sont intimement liés. L’exode rural diffus depuis les années 1960, suivi par les invasions israéliennes (les plus importantes en 1978, 1982 et 2006) et l’occupation du Sud-Liban (1982-2000), mena à la transformation des principales villes (Fawaz et Peillen, 2003). Les migrations de retour des villes libanaises vers les villages et les allers et retours avec les pays d’Afrique de l’Ouest ont renforcé le lien entre l’urbain et le rural. Dans le Jabal ‘Amil, al-Nabatiyya était un village en 1890 ; il est devenu ville en 1934, et la capitale du district administratif qui porte son nom (Mazraani, 2012).

In Lebanon today, the rural and the urban are very closely linked. The extensive rural exodus since the 1960s, followed by Israeli invasions (the most important in 1978, 1982 and 2006) and occupation of South Lebanon (1982-2000), led to the transformation of the main cities (Fawaz and Peillen, 2003). Return migration from Lebanese cities to villages, and migration to West African countries and back strengthened the link between the urban and the rural. In Jabal ‘Amil, the city of al-Nabatiyya was a village in 1890; it developed into a town in 1934 and is now the main city and capital of the administrative district of al-Nabatiyya (Mazraani, 2012).

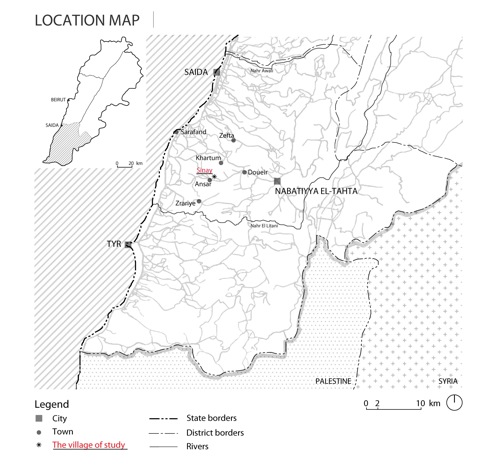

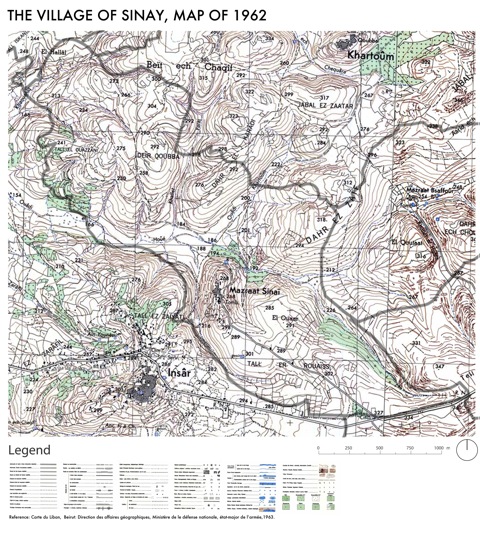

Sinay, un finage de 6 km², est situé dans le district d’al-Nabatiyya, à 89 km de Beyrouth et à 13 km de la ville d’al-Nabatiyy (voir figure 1). Comme n’importe quel autre village, Sinay est doté d’une société particulière, d’un environnement construit, d’espaces ouverts productifs et d’un environnement naturel. Les principales zones agricoles du village (fig.2) sont dahr al-zayf, dahr karady et dayr qubba (ou al-duhur), ainsi que la vallée entre ces collines où coule un cours d’eau intermittent. Les villageois se sont d’abord installés sur une quatrième colline entourée de terrasses agricoles. Ils appellent cette zone le vieux village. Le plateau s’étendant depuis ce vieux village est découpé en deux : al-hamra,partiellement couvert par une formation de maquis de chênes et buissons conquise par l’expansion du village, et al-hamra khallat al-sahra, au sud de la principale rue de Sinay, où la première extension du bâti a commencé.

Sinay, a 6sq km village, is located in the district of al-Nabatiyya – 89km away from Beirut and 13km from the city of al-Nabatiyya (see figure 1). As any other village, Sinay comprises a particular society, a built environment, open spaces as productive units and a natural environment. The main agricultural zones of the village (fig.2) are dahr al-zayf, dahr karady and dayr qubba also known as al-duhur as well as the valley between these hills, where a seasonal stream passes. The villagers first settled on a fourth hill surrounded by terraced agriculture. They refer to that area as the old village. The plateau extending from the old village is divided into two area: al-hamra partly covered by a maquis formation of oaks and shrubs and now dominated by the urban development of the village; and ‘al-hamra khallat al-sahra’, the area south of the major street of Sinay, where the first extension of the village started.

Figure 1 : Carte de localisation du village d’étude à deux échelles différentes

Figure 1: Location map showing the village of study at two different scales.

Figure 2 : Carte historique de la région en 1962, avec le tracé des limites municipales actuelles. (La carte montre les noms locaux des différentes zones, l’orthographe a été gardée en translitération des termes originaux en français).

Figure 2: Historical map of the region in 1962, with an outline of current municipal borders. The map shows the local names of the areas – the spelling was kept as per the original French transliteration.

Sinay compte aujourd’hui une population officielle d’environ 1800 habitants, dont 680 adultes d’après la dernière liste électorale[1]. Parmi ceux-ci, environ 400 vivent à temps plein dans le village tandis que plus de 150 vivent et travaillent en Afrique de l’Ouest (principalement à Abidjan) ; les autres vivent dans des villes comme Beyrouth et Saida. Sur 350 unités d’habitation, 100 sont habitées ou possédées par des personnes extérieures au village. Les émigrés résident partiellement au village : ceux qui vivent en Afrique y passent des vacances (le plus souvent un mois par an) et ceux qui vivent à Beyrouth viennent souvent les week-ends. Tous les villageois appartiennent à la communauté chiite, un fait qui, nous le verrons, a son importance pour expliquer comment ils peuvent négocier leurs droits dans le système politique libanais.

Sinay today has a registered population of approximately 1,800 persons, with 680 adults according to the last electoral list.[2] Of these, around 400 live full-time in the village and more than 150 people live and work in West Africa (mainly in Abidjan); the rest live in cities such Beirut and Saida. We find in the village around 350 housing units, 100 of which are inhabited or owned by outsiders to the village. Emigrants reside part-time in the village: those living in Africa spend some holidays in the village (usually one month a year), and those living in Beirut often come over the weekends. All villagers belong to the Shi‘ite community, a fact that we shall find relevant to the path that their negotiation of right took in the Lebanese political system.

Les revenus et les activités socio-professionnelles sont diversifiés : on a là des agriculteurs, des ouvriers en bâtiment, des carriers, des commerçants, des mécaniciens, des garagistes, des entrepreneurs, des cuisiniers et des fonctionnaires ; les migrations ont accru les inégalités sociales. L’agriculture dans le village est devenue une activité marginale à la fin du XXe siècle. Aujourd’hui quatorze familles seulement sont agricultrices : trois d’entre elles à temps plein, toutes les autres à temps partiel.

Livelihood and socio-professional activities are diversified: we find farmers, construction workers, quarry workers, shop workers, mechanics, garage owners, entrepreneurs, cooks and state employees. Migration led to increased social inequalities among the villagers. Agriculture in the village became a marginal activity during the late 20th century. Today only fourteen families are farmers: three of them farm full-time, while the rest are part-time farmers.

L’évolution de Sinay vers une agriculture moderne peut être découpée en trois périodes.

The modern agrarian evolution of Sinay can be divided into three periods:

(1) De la fin du XIXe siècle aux années 1930, Sinay formait un espace agricole possédé par un seul landlord ; il était cultivé par des paysans sans terre qui donnaient jusqu’aux années 1930 une partie de leur récolte au propriétaire. Au fil des ans, les paysans travaillaient les mêmes parcelles, que leur avaient attribuées le landlord. Les principales cultures, pluviales, étaient les lentilles, le blé et l’orge ; les paysans avaient des troupeaux conséquents de vaches et de chèvres, pour le lait et la viande, et pour les travaux agricoles. Les animaux étaient utilisés pour créer des terrasses sur lesquelles on semait les cultures. Leur force de traction limitait aussi la forme et la taille des parcelles. Les paysans vivaient sur une petite partie des terres villageoises (aujourd’hui connues comme le vieux village). Durant cette période, chaque paysan avait le droit d’utiliser un lopin pour construire sa maison. Les habitants n’avaient pas de titres de propriété, mais détenaient des documents où le landlord reconnaissait l’existence de leur habitation. Une relation de dépendance sociale associait le grand propriétaire aux cultivateurs qui travaillaient sa terre et les cultivateurs aux propriétaire qui les protégeait.

(1) From the later 19th-century to the 1930s, Sinay formed an agricultural space owned by a single landlord and cultivated by landless peasants who until the 1930s gave the landowner a share of their cultivated crops. Over the years, peasants worked the same parcels, assigned by the landlord. The main crops planted were rain-fed lentils, wheat and barley. Peasants had substantial holdings of animals such as cows and goats, for milk and meat products, as well as for agricultural operations. Animals were used to create terraces on which crops were planted; their power of traction also limited the form and size of farmers’ plots. The peasants lived in a small area of the village lands (now known as the old village). During this period, each peasant family had a right to use a small plot of land for building his or her house. However, inhabitants did not have any property titles. For their houses, they held deeds wherein the landlord acknowledged their occupation of houses. This social dependency relation bound the landlord to the cultivators for working land, and the cultivators to the landlord for protection.

(2) Entre les années 1930 et 1960, Sinay est devenue un balda, c’est-à-dire un village rattaché à la ville la plus proche, Ansar. Le système agraire du village évolua et l’agriculture capitaliste se développa. Le principal propriétaire du village[2] voulait développer l’espace villageois comme une vaste unité agricole de production : il introduisit des cultures d’exportation comme le tabac, encouragea la plantation d’arbres fruitiers (particulièrement les oliviers), et établit des contrats (mugharasa) avec des agriculteurs pour planter des arbres. Le mugharasa est un accord entre un propriétaire et un agriculteur, par lequel celui-ci plante une parcelle d’arbres fruitiers ; après quinze ans, le paysan devient propriétaire de la moitié de la parcelle. Petit à petit, les villageois ont ainsi acquis de petites portions de terre agricole. Cette période était aussi marquée par de grandes vagues de migrations internes et externes. Les remises des migrants permirent aux habitants du village d’acheter leur maison ou un petit terrain sur lequel construire de nouvelles habitations. La structure sociale et spatiale de la propriété de la terre passa d’un propriétaire unique à un certain nombre de propriétaires extérieurs, parmi lesquels certains développèrent des vergers. Cependant, la majeure partie de la terre de Sinay restait dans les mains du Propriétaire α.

(2) Between the 1930s and the 1960s, Sinay became a balda, or a village attached to the nearest town Ansar. The agrarian system of the village evolved and capitalist agriculture developed. The major owner[3] in the village aimed at developing the village’s space as a large agricultural productive unit: he introduced cash-crops such as tobacco, encouraged the planting of fruit trees (especially olives), and drew up contracts (mugharasa) for tree planting with the farmers. Mugharasa is an agreement between the landlord and the farmer, whereby the farmer plants a parcel with fruit-bearing trees. After fifteen years, the farmer comes to own half the parcel. Slowly, villagers thus came to own small areas of agricultural land. This period was also marked by large waves of internal and external migration. Remittances allowed inhabitants of the village to buy their houses or small plots on which to build new houses. This changed the social and spatial structure of landholdings in the village from a single landlord to a number of outside landowners, some of whom developed orchards. However, the great part of the land of Sinay remained in the hands of Owner α.

(3) A partir des années 1960, après que le Propriétaire α rencontra des problèmes financiers, il décida de découper sa propriété de Sinay et de la vendre pour payer ses dettes. Mais comme les parcelles étaient vastes et trop chères pour la population locale, des « extérieurs » furent les principaux acquéreurs. Hormis une petite tentative rapidement abandonnée, les nouveaux propriétaires n’investirent pas dans le développement agricole du village, mais plutôt dans le secteur des services et les projets miniers. En parallèle, la mécanisation de l’agriculture mena à un déclin de sa demande en main d’œuvre. La grande majorité des paysans quittèrent l’agriculture ou devinrent pluriactifs, pratiquant principalement des récoltes peu intensives en travail – le blé et l’orge – aux dépens des cultures d’exportation. Les terres ne furent plus valorisées par la production agricole mais comme terrains à bâtir voire comme simples moyens de spéculer pour les plus gros propriétaires. Le village aujourd’hui se trouve habité par des populations locales ou venues de l’extérieur, correspondant à divers groupes socio-économiques et diverses activités. Le paysage aussi s’est modifié, passant d’un espace agricole à un espace multifonctionnel. Ces transformations entrent en contradiction avec la définition traditionnelle d’un village et de la ruralité.

(3) Starting in the 1960s, after Owner α faced financial problems, he decided to parcel his holdings in Sinay and to sell the plots to pay off his debts. But because the plots were large and expensive for local people, ‘outsiders’ were primarily those who bought land in the village. Aside from one small attempt, rapidly abandoned, the new owners did not invest in agricultural development in the village. The new investments focused mainly on service and mining projects. In tandem, the mechanisation of agriculture led to a decline in the demand for labour in village agriculture. The great majority of the farmers either quit agriculture or became pluri-active, planting mainly low-labour-intensive crops – wheat and barley – at the expense of cash-crops. The value of lands for agricultural production gave way to their valuation for building plots or for sheer financial speculation for large owners. The village today is inhabited by locals and non-locals, with many socio-professional groups and activities. The landscape too changed from an agricultural space to a multifunctional one. These transformations challenge the traditional definitions of what a village and rurality may be.

III. Les revendications de leurs droits par les habitants

III. People’s claims for rights

Première histoire : l’accès à la terre agricole

Story 1: Access to agricultural land

Notre étude de cas met en lumière la persistance de droits d’usage coutumiers en ce qui concerne la terre agricole. Selon les villageois, leur sujétion au grand propriétaire prit ses racines dans ce qu’ils appellent la période al-iqta‘, période « féodale » des systèmes d’octroi de terre (Lutsky, 1987). Jusqu’à 1939, du temps du mandat français sur le Liban, l’ensemble de Sinay était enregistré comme la propriété d’un seul homme, figure politique majeure de la ville de Saida dont le descendant siège aujourd’hui au Parlement libanais. Malgré la taille de l’exploitation, le travail effectif de la terre était réalisé manuellement par les familles paysannes, la mécanisation ne se généralisant que dans les années 1950. Il faudrait étudier plus en détail l’histoire de la propriété foncière, mais jusque dans les années 1950, la terre était travaillée par de petites unités familiales de métayage, avec des droits d’usage établis sous fort contrôle du propriétaire. Les deux cinquièmes de la récolte lui étaient payés, tandis que tous les autres facteurs de production étaient fournis par le cultivateur. A la différence de la Syrie voisine, aucune réforme foncière ne fut jamais menée au Liban.

This case study sheds light on the persistence of customary use-rights to agricultural land. Villagers speak of their subjection to landlord power having its roots in what they call the period of al-iqta‘, ‘feudal’ or land grantsystems (Lutsky, 1987). As late as 1939 under the French Mandate for Lebanon, all of Sinay was registered as the single property of one landlord, a prominent political figure from the city of Saida, whose descendant sits in the Lebanese parliament today. Although the holding was large, actual cultivation was by peasant families, mechanization only becoming widespread during the 1950s. We have yet to document the history of land tenure in all its detail, but until the 1950s, the land was worked by small family share-cropping units with established use-rights under strong landlord control. Two-fifths of the crop were paid to the landlord for use of the land while all other factors of production were provided by the cultivator. Unlike in neighbouring Syria, land reform was never implemented in Lebanon.

A Sinay, un tel système de métayage familial survécut dans la zone de al-duhur (ou dayr qubba) (Figure 2) jusqu’au début de la guerre civile en 1975 - bien que la propriété de la terre changeât de main pour un propriétaire absentéiste qui y investit l’argent gagné en Afrique de l’Ouest. Comme l’agriculteur travaillait les mêmes parcelles au fil des années, il acquérait un droit d’usage sur elles. Ce droit était transmis à ses descendants. Si le cultivateur voulait cessait de travailler la terre, il pouvait transférer son droit (généralement à un membre de sa famille). Mais si le paysan abandonnait son droit d’usage, il ne pouvait pas le réclamer par la suite. Cette mise en culture continue engendrait une entente sociale et l’acceptation de ce droit, quels que pussent être les changements de propriétaires ou de système agraire au fil des ans.

In Sinay such small family sharecropping farming survived in the area of al-duhur (or dayr qubba) (see location on figure 2) until the beginning of the civil war in 1975, although ownership of the land itself changed hands to an absentee owner who invested money made in West Africa. As the same farmer worked the same plots over the years, he or she gained a right of cultivation or right of use of specific parcels. This right was transmitted to the farmer’s descendants. If the cultivator wanted to stop using the land, he could transfer his right (usually to a family member or relative). But if the farmer gave up his use-right, he could not reclaim it subsequently. This continuity of cultivation created a social understanding and acceptance of right. Across the different owners and changes in the agrarian system over the years, this type of agricultural land use-right persisted.

Le système continua au village jusqu’au début de la guerre civile, alors qu’à ce stade, le caractère politique de ce régime d’iqtaʿ avait disparu de la région depuis longtemps et que l’agriculture capitaliste s’était largement développée depuis les années 1950. Entre les années 1950 et 1970, bien que le nombre de familles cultivant la terre décrût, leurs droits de l’utiliser se maintinrent. Les photographies aériennes de 1975 révèlent que plus de 70% des terres (le reste étant surtout incultivable) demeuraient cultivés à al-duhur. Les cultures étaient principalement pluviales, blé, lentilles et orge.

This system continued in the village until the beginning of the civil war, although at this stage, the political character of the iqtaʿ regime in the area had long gone, and capitalist agriculture had been developed more widely in the region from the 1950s. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, although the number of families cultivating decreased, their rights to use of land continued. Aerial photographs from 1975 reveal that more than 70% of the land (the rest mostly being inaccessible to farming) was cultivated in al-duhur. The crops were primarily rain-fed field crops, such as tobacco, wheat, lentils and barley.

En 1975, du fait des combats à Beyrouth il devint difficile d’obtenir de la ville de la farine panifiable. Encouragés par le nombre croissant d’habitants qui avaient rejoint les partis de gauche, les agriculteurs refusèrent de donner aux propriétaires les deux cinquièmes de leur production et distribuèrent le blé qu’ils avaient récolté aux autres villageois. Ils négocièrent plus tard avec les propriétaires une réduction de leur quote-part, de deux cinquièmes à un cinquième.

In 1975, the fighting in Beirut made it difficult for the villagers to obtain flour for bread from the city. Encouraged by the growing number of villagers who had joined leftist parties, the farmers refused to give the owner of the land two-fifths of their production and distributed the wheat they harvested to other villagers. The farmers later met with the owner of the land and negotiated a reduction of his share from two-fifths to one-fifth.

En 1998 le village de Sinay, qui dépendait jusque-là administrativement de la ville voisine de Ansar, devint une municipalité indépendante. Dès lors, les droits d’usage furent « formalisés ». Un accord fut signé entre les différents agriculteurs, le propriétaire et le maire du village, qui garantissait les droits d’usage en échange de 20% de la récolte payée au propriétaire. Il donna aussi à ce dernier le droit d’interrompre l’accord à condition de donner un an de préavis.

In 1998 the village of Sinay, which had earlier depended administratively on the neighbouring town of Ansar, became an independent municipality. Since then, use-rights were ‘formalised’. An agreement was signed between the different farmers, the landowner and the mayor of the village. This agreement guaranteed the use-rights of farmers in return for 20% of the produce to be paid to the owner. It also gave the owner the right to terminate this agreement on condition of giving a year’s notice to the farmers.

Al-duhur (cf. figure 3) est une partie du finage où les agriculteurs bénéficient toujours de leur droit d’usage. En septembre 2013, un incident eut lieu entre ceux-ciet le propriétaire. Il déclara soudain qu’il interrompait le contrat et louait la terre à une tierce partie contre un loyer fixe en numéraire. Cet intermédiaire sous-louerait aux agriculteurs. Mais ceux-ci eurent peur de plus pouvoir cultiver la terre, ou de devoir la louer à un prix trop élevé. Les deux éventualités menaçaient leur droit d’usage. Bien qu’il n’y ait pas de clause dans l’accord signé en 1998 garantissant leur futur usage de la terre, ils s’organisèrent et refusèrent de céder leurs parcelles. Comme le déclara un agriculteur : « C’est le droit du propriétaire de cultiver sa terre personnellement, mais nous n’allons pas lui laisser louer sa terre à un autre que nous ».

Al-duhur (see figure 3) is an area of the village where farmers still enjoy this agricultural land-use right. In September 2013, an incident took place between farmers cultivating areas of al-duhur and the landowner. The latter suddenly declared that he would terminate the agreement and lease the land to a third party for a rent paid once in cash. This lessee was then to sublet the different plots to the farmers. The farmers feared that they would either not be able to plant the land any longer or would have to rent it at a high price. Either eventuality would threaten their use-rights. Although there was no clause in the agreement signed in 1998 assuring the farmers of the future use of the land, they took action and refused to leave their plots. One farmer stated: “It is the owner’s right to plant his land personally, but we will not let him rent it to someone other than us”.

Figure 3 : Vue d’ensemble de la zone agricole de al-duhur, montrant les différentes parcelles agricoles (Gharios, 2013).

Figure 3: Overview of the agricultural area of al-duhur, showing the different agricultural plots (Gharios, 2013).

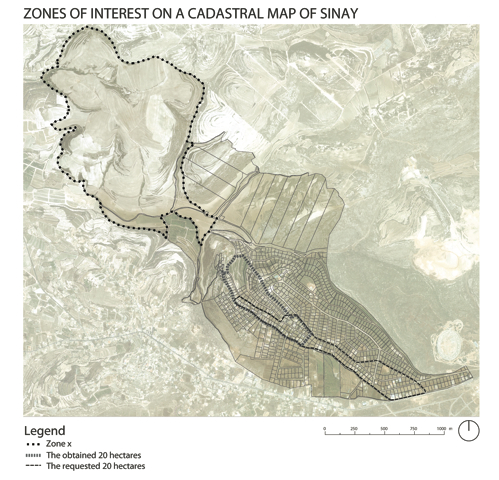

Les agriculteurs menèrent une action collective pour protéger leurs droits d’usage. Ils se constituèrent en groupe pour négocier avec le propriétaire : sept paysans, qui mettaient en valeur 121 hectares en agriculture pluviale (soit 78% de la zone x, cf. figure 4). Le propriétaire demeura au Sénégal durant le conflit, mais demanda à son agent (wakil) de le représenter dans les négociations. Le maire du village agit comme médiateur. Après plusieurs mois de négociations, un nouvel accord fut trouvé dans lequel les 20% de la production étaient remplacés par un loyer en numéraire. Une délimitation précise des terres fut alors menée pour définir précisément les loyers de chacun. Dans les mois suivant la négociation, un agriculteur au moins décida de ne pas ensemencer sa terre, de peur de perdre de l’argent.

Farmers developed collective action to protect their use-rights. All of the farmers met and created a group to negotiate with the landowner. This confrontation opposed seven farmers who cultivated rain-fed crops over 121 hectares (some 78% of Zone x, see Figure 4: ‘zones of interest’) to the owner, who remained in Senegal during the conflict but asked his agent (wakil) to represent him in the negotiations. The mayor of the village acted as mediator in the conflict. After several months of negotiation, a new agreement was signed in which the 20% of production was replaced by a cash-rent by plot. A detailed survey of the land use was therefore conducted to define the exact areas planted by each cultivator and to determine the individual rents. In the months following the negotiation, at least one farmer decided not to plant his land out of fear of losing money.

Figure 4 : Carte de Sinay montrant les « zones d’intérêt » où les contestations eurent lieu. Tant la photographie aérienne que la carte cadastrale sont de 2005 et fournies par le Conseil National de Recherche Scientifique libanais.

Figure 4: Map of Sinay showing the ‘zones of interest’ where contestations took place. Both the aerial photograph and the cadastral map are from 2005, and given by the LCNRS (Conseil National de Recherche Scientifique Libanais).

Ce conflit avait mis aux prises un droit de propriété individuelle presque illimité et des droits d’usage agricoles. Aussi forts que soient ces derniers, il n’y aurait eu aucune contestation si le propriétaire avait envisagé de cultiver sa terre lui-même. En pareil cas, même le droit d’usage le plus ancien aurait été impuissant face au droit de propriété. L’accord obtenu montra la capacité de résistance d’acteurs qui détiennent des droits socialement établis face au pouvoir légal du propriétaire. Cependant, le fait que la résistance soit limitée à la communauté paysanne de al-duhur reflète le déclin de l’agriculture pluviale dans l’économie des ménages. L’agriculture à Sinay est devenue secondaire : le travail en ville, la migration de travail en Afrique de l’Ouest et dans le Golfe, et les transformations du système agraire régional depuis les années 1950 ont réduit le poids de ce secteur dans le village. L’agriculture a même cessé d’être la principale source de revenus pour les familles de cultivateurs, à l’exception d’un agriculteur et d’un vieil éleveur, et seuls le travail à l’étranger et la mécanisation de l’agriculture assurent la résilience de la production agricole. Cependant l’action collective des paysans a affirmé leur droit à travailler la terre et exprimé quelle valeur gardait l’activité agricole, non pas simplement comme une occupation à temps partiel, mais comme l’expression de l’identité villageoise.

This conflict pitted an almost unfettered individual property right against agricultural land-use rights. Indeed, so strong is the former that there would have been no contestation had the owner planned to cultivate the land himself. In that case even the most longstanding use-right would have been powerless before the property right. The agreement reached demonstrates the resistance of actors who hold socially established rights to work land in the face of the legal power of the landlord. Yet, that the resistance was limited to the farming community of al-duhur reflects the reduction of rain-fed agriculture in the household economy. Agriculture in Sinay has become a secondary component: work in the city, labour migration to West Africa and the Gulf, and the transformations of the regional agrarian system since the 1950s reduced the weight of this sector in the village. Agriculture is not the main source of income in the village even for the farming families, save one farmer and one older herder. Migrant labour and the mechanisation of agriculture allow for the resilience of agricultural production. Yet the collective action of the farmers does assert their right to work the land and expresses the value of agricultural activity, not simply as a part-time occupation, but as an expression of the village’s identity.

Deuxième histoire : l’accès au logement

Story 2: Access to housing

Si l’accès à l’agriculture pluviale n’impliquait que quelques villageois, tous se trouvèrent concernés par un conflit avec un autre propriétaire foncier, extérieur au village, à propos de terrains à bâtir.

If access to rain-fed agriculture engaged only some villagers, all were concerned by a conflict with another landowner from outside the village over land for housing.

En 1956, Sinay comptait environ 400 habitants, qui vivaient dans le vieux village, petite fraction du territoire de la municipalité. La plupart des maisons à cette époque comptaient deux pièces : l’une pour vivre et l’autre pour le bétail. Le reste du finage était voué à l’agriculture et au maquis, en vastes parcelles possédées par une poignée d’individus riches, extérieurs au village, qui avaient acheté la terre au propriétaire originel en quelques transactions.

In 1956, Sinay had about 400 inhabitants, who lived in the old village site, a small area of the municipal territory. Most of the houses at that time consisted of two rooms: one for living and the other for the cattle. The rest of the village land was given over to agriculture or scrub forest, in large blocks owned by a handful of wealthy individuals from outside the village who had bought the land from the original landlord in a small number of transactions.

Dans les années 1960, un tremblement de terre détruisit de nombreuses maisons, et une aide financière de l’Etat permit leur reconstruction et leur extension. Cependant, la partie bâtie du village restait très limitée par rapport à la population croissante de Sinay. Comme nous l’avons noté, les faibles perspectives pour les métayers encouragèrent beaucoup de résidents à quitter l’agriculture et chercher d’autres types de métiers. De jeunes hommes du village migrèrent vers Beyrouth et l’Afrique de l’Ouest, suivant la voie de la migration individuelle ouverte à la fin du XIXe siècle. Bien avant le début de la guerre civile, les remises des migrants représentaient une source importante de revenu pour de nombreuses personnes au village. Mais en 1975, la guerre civile libanaise prit la forme d’une guérilla urbaine. De nombreux villageois vivant et travaillant à Beyrouth revinrent au village. L’étroit site initial devint rapidement encore plus surpeuplé. Or, une rumeur se fit jour : l’investisseur foncier qui contrôlait la terre agricole à al-hamra (également appelée tell er Roueiss sur la carte historique de Sinay, figure 2) comptait profiter de la valeur croissante de l’immobilier en lotissant officiellement le terrain pour vendre des parcelles plus petites à des prix beaucoup plus élevés. Il était libre de le faire, en principe, vu qu’au Liban légalement toute terre est virtuellement disponible à la construction (de plus, les taxes sur les transactions immobilières sont minimes) (Bakhos, 2005). Pour l’élite libanaise, le sud appauvri faisait figure de « nouvelle frontière » pour la spéculation immobilière.

In the 1960s, as a result of an earthquake that destroyed many houses, financial support from the state allowed for the reconstruction and expansion of several homes. However, the built-up area of the village remained very small compared to the growing population in the village. As we have noted, poor prospects as sharecropping farmers encouraged many residents to leave agriculture and to search for other types of jobs. Young men from the village migrated to Beirut and to West Africa, building on paths of individual migrants opened from the late 19th century. From well before the beginning of the civil war, remittances represented a significant source of livelihood for many people in the village. Yet in 1975 the Lebanese civil war took the form of urban fighting. Many villagers working and living in Beirut returned to the village. The small area of the village site became ever more crowded. In the face of this, the property investor who held the agricultural land in al-hamra (also called tell er Roueiss on figure 2: Historical map of Sinay) was rumoured to be planning to cash in on the increasing value of real estate, by parcelling the land officially so as to sell smaller plots at much higher prices. He was free to do this in principle, given that in Lebanon virtually all land is legally open to construction (and the taxes paid on real estate transactions are minimal) (Bakhos, 2005). For Lebanon’s elite, the impoverished south held the promise of a ‘new frontier’ for land speculation.

Avec l’escalade dans la guerre civile et le vide politique des premières années, les villageois commencèrent à penser s’emparer de la terre pour y construire. Après plusieurs réunions, ils élaborèrent un projet. On décida que chaque famille obtiendrait une zone proportionnelle au nombre de fils âgés de 20 ans et plus : 0,1 ha pour un fils, 0,2 ha pour deux à quatre fils, et 0,3 ha pour cinq fils ou plus. Un recensement révéla que la surface totale requise était alors de 20 ha. Les villageois créèrent un comité de trois personnes responsables de l’étude du projet : sélectionner la zone, dessiner un plan, et découper les terrains. Le site choisi était sur une bonne terre, en terrain plat, à al-hamra, facile à bâtir, et rejoignant la principale route de al-Nabatiyya. Avec l’aide d’un ingénieur, le comité élabora un plan découpant l’espace par famille et par quartiers. Ce plan prenait en compte les anciens droits d’usage de la terre agricole afin de réduire les conflits potentiels. Les villageois qui cultivaient la terre dans une zone obtenaient des terrains à bâtir dans la même zone.

With the escalation of the civil war and the political vacuum in its early years, villagers began to think of taking land for building by force. After several meetings, the villagers developed a plan. They drew up a census to determine the total area required. It was agreed that each family should obtain an area proportional to the number of sons older than twenty years in age: 0.1 hectare for one son, 0.2 ha for two to four sons, and 0.3 ha for five or more sons. This census revealed that the total area needed was 20 ha. The villagers then created a three-person committee responsible for the study of the project: to select the land, to develop a plan, and to partition the land. The site selected was located on good flat land in al-hamra, easy to build on, and adjoining the main road from al-Nabatiyya to the village. With the help of an engineer, the committee developed a plan dividing the space by family into neighbourhoods. This plan took into account previous farming land-use rights so as to reduce potential conflicts. Villagers who cultivated land in an area were to obtain building plots in the same zone that they farmed.

En 1976, certains bénéficiaires commencèrent à préparer leurs terrains, tandis que d’autres commençaient même à bâtir. Mais en 1977, à l’appel du propriétaire et des investisseurs, des hommes du mouvement Amal[3] extérieurs au village intervinrent pour tenter d’interrompre les travaux en cours, afin de protéger les droits du propriétaire privé. Bien que la majorité des villageois concernés fût membres d’Amal, il y eut des heurts. Les leaders d’Amal parvinrent à interrompre la construction et à transférer la gestion du conflit au Conseil chiite (majlis shiʿi)[4]. Des négociations commencèrent entre le propriétaire et les villageois. Au majlis, le propriétaire tenta de criminaliser l’action des villageois, en insistant sur son illégalité. Les villageois, eux, défendaient leur droit à vivre de manière décente dans leur village, s’appuyant sur des principes religieux et sur l’enracinement local, critiquant les prix élevés demandés par le propriétaire pour les terrains.

In 1976, some beneficiaries started preparing their lands, while others even started building. In 1977, at the request of the landowner and investors, a force from the Amal movement[4] from outside the village intervened and tried to stop the work in order to protect the rights of the private owner. Although the majority of the villagers concerned were members of the Amal movement, clashes took place. Amal’s leadership managed to stop the construction and transferred the management of the conflict to the Shiite Council (majlis shiʿi).[5] Negotiations were undertaken between the landowner and villagers. In the majlis, the owner tried to criminalize the villagers’ action, insisting on its illegality, while the villagers defended their right to live honourably in their village in terms of religious principles and local belonging, criticizing the high price demanded by the owner for the plots.

Amal ne voulait soutenir aucun des groupes en conflit, puisque le mouvement avait besoin du soutien des deux. D’un côté, la force du mouvement Amal sur le terrain depuis 1978 reposait sur de jeunes militants de la région, y compris des jeunes de Sinay. D’un autre côté, l’orientation économique d’Amal était fondée sur la protection de la propriété privée (Waraqat amal, s.d.). De plus, Amal dépendait des dons financiers et du soutien de personnalités riches comme le propriétaire de la terre en question. Aussi les négociations n’avancèrent-elles guère.

Amal did not want to support one or the other of the conflicting groups because they needed the support of both. On the one hand, the strength on the ground of the Amal movement since 1978 was based on the young activists in the region, including youth from Sinay. On the other hand, the economic orientation of Amal was based on the protection of private property (Waraqat amal n.d.). Furthermore, Amal relied on the financial donations and backing of wealthy people such as the owner of the land in question. The negotiations thus stagnated.

Des changements politiques plus amples embrassèrent Sinay et la région. Le village se trouva sous occupation israélienne directe entre 1982 et 1985, et des groupes de résistance locale, très liés au mouvement Amal, se formèrent spontanément. Ces groupes étaient faiblement équipés, n’utilisant pas d’armes de guerre mais de simples fusils de chasse. Les villageois risquaient leur vie pour défendre une terre qu’ils ne possédaient pas, et qu’en général ils ne pourraient jamais posséder. A cette époque, seuls 5% de la terre du village appartenaient à des propriétaires locaux. Leur résistance – pour Sinay et pour le Liban – donna plus de poids aux exigences des villageois. Leur position dans le marchandage s’améliora : ils insistèrent sur leur rôle dans la libération du village, l’opposant au rôle purement financier du propriétaire du terrain. Un des leaders du village remarqua : « tous les gens qui veulent des terrains se sont battus contre les Israéliens tandis que le propriétaire a seulement donné de l’argent au mouvement. Tout l’argent arabe n’a pas libéré la terre arabe, mais nous, nous avons libéré notre terre ». Cependant, à la suite de la libération de cette partie du Sud-Liban en 1985 – la partie plus au sud jusqu’à la ligne d’armistice ne fut pas libérée avant 2000 – les demandes en terre et leur prix augmentèrent considérablement, ce qui encouragea le développement immobilier dans les zones libérées. Le propriétaire foncier à Sinay commença à diviser sa terre en parcelles à bâtir et fixa le prix de vente à 40 000 livres libanaises pour 0,1 hectare. Les villageois en appelèrent alors une fois de plus à l’autorité d’Amal pour intervenir, et une nouvelle phase de négociation commença.

Wider political developments engulfed Sinay and the region. The village came under direct Israeli occupation between 1982 and 1985, local resistance groups formed spontaneously in the village, closely related to the Amal movement. These groups were poorly equipped, using non-military weapons such as ordinary hunting guns. The villagers risked their lives to defend land that they did not, and in general could not, own. At the time only some 5% of the village land was owned by local people. Their resistance – for Sinay and for Lebanon – gave some strength to the villagers’ demands. As a result, their bargaining position improved: they emphasized their role in the liberation of their village, pitting it against the purely financial role of the land owner. One of the village leaders noted: “all the people who seek land fought against the Israelis while the owner only paid money to the movement. All the Arab money did not free Arab land, but we freed our land.” Yet, following the liberation of this part of the South in 1985 – the deeper South to the Armistice line not being liberated until 2000 – the demand for land and its price increased dramatically, encouraging real estate development across the liberated areas of South Lebanon. The land owner in Sinay began to set in motion the division of his land into housing plots and fixed the selling price at 40 000 LL per 0.1 hectare. The villagers again appealed to the leadership of Amal to intervene and a new phase of negotiation began.

A la fin de 1987, les deux parties trouvèrent un accord, non sans faire de compromis de part et d’autre. Le propriétaire accepta de vendre 20 hectares aux villageois au prix originellement fixé (environ 15 000 livres libanaises pour 0,1 hectare). Mais il changea la localisation du terrain : elle se trouva moins avantageuse, puisque environ cinq hectares étaient sur un terrain accidenté, difficile à bâtir. Le propriétaire exigea aussi que l’argent lui fût versé en une seule fois. Les villageois acceptèrent ces conditions et demandèrent l’assistance d’une riche personne du village, qui avait fait fortune en Afrique de l’Ouest, pour avancer le montant fixé ; par la suite, les bénéficiaires lui rembourseraient leur part de la somme totale. De même, le mouvement Amal garantissait la construction de routes et la fourniture d’électricité par le ministère des Travaux Publics, qui à l’époque était son allié politique.

At the end of 1987, the two sides reached an agreement, not without compromises from both. The owner agreed to sell 20 ha to the villagers at a third of the original price (around 15 000LL per 0.1 hectare). But the owner changed the location of the land chosen by the villagers. The new location was less advantageous, as about five hectares were on hilly terrain difficult for construction. The landowner also demanded that the money be paid as one block payment. The villagers accepted these conditions and requested the assistance of a rich person of the village (who had made money in West Africa) to advance the amount agreed. Later the beneficiaries would each repay him their parts of the whole. Likewise, the Amal movement guaranteed the construction of roads and supply of electricity at the expense of the Ministry of Public Works. The then Minister of Public Works was a political ally of the Amal movement.

Une fois le conflit externe résolu, apparut un nouveau conflit, interne celui-là. Le changement de localisation remettait en question les anciens plans et les accords de partage entre les villageois. La concurrence pour choisir les terrains entraîna des tensions entre les différents bénéficiaires. Qui plus est, l’homme qui finançait la terre obtint 3 ha, et quatre médiateurs dans le conflit, tous extérieurs au village, obtinrent chacun 0,1 hectare. Cela réduisait la surface qui restait à distribuer. De plus, les différences physiques entre les parcelles sur terrain accidenté et sur partie plane créèrent d’autres conflits. Le financeur de l’achat du terrain fixa alors différents prix en fonction de la localisation : les parcelles sur la route principale étaient plus chères que celles plus éloignées, celles en pente moins chères que celles sur terrain plat. Ainsi, les différences économiques entre les villageois – qui résultaient des migrations et des remises – prirent de plus en plus une forme spatiale.

Once the external conflict was resolved, a new internal conflict developed. The change of location affected the old plans and agreements over the distribution of plots between the villagers. Competition over the choice of plots engendered tensions between the different beneficiaries. Moreover, the man who financed the land obtained three hectares, and four mediators in the conflict, all outsiders to the village, obtained 0.1 hectare each. This reduced the remaining land available for distribution. Likewise, the physical difference between the plots in the hilly and the flat land created yet other conflicts. The man who financed the land purchase set different prices depending on the location of parcels: parcels on the main road were more expensive than those further away, and plots on a slope were cheaper than those on level ground. So, economic differentiation between the villagers – resulting from migration and remittances – increasingly took spatial form.

Trois conséquences de cette longue lutte pour des terrains à bâtir doivent être notées. Premièrement, les responsables du mouvement Amal ont joué un rôle central en réorientant le conflit : de revendications au logement comme un droit, on est passé au simple paiement de la terre villageoise - certes à des prix acceptables et sans spéculation abusive. Ce changement reflète le principe d’Amal : protéger et gérer le droit de propriété privée tout en essayant de garantir les moyens de subsistance des villageois. Deuxièmement, la distribution de terrains à bâtir mit en lumière l’émergence d’inégalités sociales au sein du village et le rôle de la migration de travail dans la différenciation de classe. Cela illustre la théorie d’Henry Bernstein selon laquelle les conflits sociaux pour la terre révèlent l’aggravation de la différenciation sociale et la formation de classes (Bernstein, 2004, pp. 190–225). Troisièmement, le conflit a principalement transformé l’occupation du sol dans cette région, qui est passée de la production agricole au logement de type urbain (voir figure 5). La construction encouragea une nouvelle expansion immobilière, le propriétaire procédant en 1990 au lotissement de tout le reste des bonnes terres de al-hamra pour les vendre comme terrains à bâtir (voir figures 2 et 4).

Three consequences of the long struggle for housing plots should be noted. First, the leadership of the Amal movement played a central role in re-orientating the conflict: from villagers’ claims to housing as an entitlement, to paying for village land, albeit at acceptable prices, free of abusive speculation. This change reflects Amal’s principle of protecting and managing private property right while trying to meet the livelihood needs of the villagers. Second, the distribution of land for housing became a showcase of emergent social inequality in the village and of the role of labour migration in class differentiation in the village. This illustrates the thesis of Henry Bernstein that social conflict over land reveals the deepening of social differentiation and class formation (Bernstein, 2004, pp. 190–225). Third, the conflict has essentially transformed land-use in this area, from agricultural production to urban housing (see figure 5). The building encouraged further real estate expansion in the village, the landowner proceeding in 1990 to parcel all the rest of the good land of al-hamra for sale as housing plots (see figure 2: map of Sinay and figure 4: ‘zones of interest’).

Figure 5 : La zone de al-hamra, où se fait l’extension urbaine (Gharios, 2013)

Figure 5: The area of al-hamra, where the urban extension is taking place (Gharios, 2013)

Plus largement, ce conflit pour le droit au terrain à bâtir révèle une contradiction dialectique. D’un côté, la possibilité de monter une revendication contre le propriétaire du terrain spéculateur, une figure très liée au mouvement confessionnel et quasi-étatique Amal, reflète la prise de pouvoir physique des villageois durant les années de résistance militaire à l’occupation. Mais d’un autre côté, l’environnement légal et étatique plus large au sein duquel Amal à la fois gouverne et représente les villageois du Sud-Liban, demeure peu favorable à la formulation d’un véritable « Droit au Village », voire d’un « Droit à la Ville ». Les villageois, on l’a vu, ont lutté pour les deux éléments qui formeraient un tel Droit : le logement et la maintien de l’activité agricole. Mais les résultats obtenus sont tout sauf le simple récit d’une victoire. Alors que les habitants ont effectivement gagné le droit pour leurs enfants de s’établir au village, le propriétaire conserva le pouvoir de transformer les meilleures terres agricoles en une vaste lotissement rurbain, où de grandes villas rappellent aux villageois pauvres la modestie de leur succès de classe, par rapport à la scène libanaise d’une économie fondée sur le pétrole et les remises des migrants. Cela rend d’autant plus précieux, et d’autant plus fragile, le succès des agriculteurs pour conserver leur droit à cultiver les terres appartenant à une personne extérieure au village. Un agriculteur à temps partiel déclarait, en montrant de la main le paysage des champs : « Bientôt, toute cette terre sera aussi lotie de maisons ».

More generally, the case concerning the right to land for habitation reveals a dialectical contradiction. On the one hand, the very possibility of mounting a claim against the land owner/speculator, a figure well tied into the quasi-state sectarian movement of Amal, reflected the physical empowerment of the villagers during the years of military resistance against occupation. But on the other hand, the wider political environment of law and state within which Amal simultaneously governs and represents southern villagers, remains highly inhospitable for the articulation of a sustained ‘Right to the Village’ or, indeed, ‘Right to the City’. Villagers, we have seen, have struggled for two of the elements that would compose such a Right: habitation and continuing agricultural production. But the resultant achievements are anything but a simple story of victory. While the villagers did win the right for their children to dwell in the village, the landowner had the power to transform the agricultural land with the best soil into a larger rurbain housing estate where large villas remind poorer villagers of their continuing modest class success on the wider Lebanese stage of the oil and remittance economy. This renders the success of the farmers in retaining their rights to cultivate the lands owned by yet another outside landowner all the more precious, yet all the more fragile. With a wave of the hand across the landscape, a part-time farmer declared: ‘In time, all this land too will be built with houses.’

Conclusion

IV. Conclusion

Nous avons fait ici l’histoire des luttes pour obtenir des droits dans un village du Sud-Liban. Comme le montre notre propos, le village est soumis à une échelle plus vaste de gouvernement qui n’a jamais admis la réforme foncière (le gros du finage reste jusqu’à aujourd’hui, et légalement, dans la main de propriétaires fonciers extérieurs), l’existence même d’une structure municipale officielle est assez récente, et l’Etat a échoué à faire un zonage et à protéger la principale ressource productive, à savoir la terre agricole, contre d’autres utilisations. L’appropriation du sol est donc très proche de l’idée abstraite d’une propriété privée absolue où les propriétaires ont un contrôle total de la terre. Du fait de son intégration exceptionnelle au sein des économies globales du pétrole et des migrations de travail à longue distance, le Liban est un bon exemple de ce que Samir Amin a décrit comme le destin du Tiers-Monde : le pillage politique de l’environnement (Amin, 2004, pp. 29–52).

We have examined here the history of struggles to obtain rights in a village of south Lebanon. As the account above reveals, the village is submitted to a wider form of government which has never admitted land reform (the bulk of the village remains legally until today the property of outside landowners), in which the very existence of any formal municipal structure was quite recent, and for which the state has failed to zone or to protect from other uses the major productive resource, agricultural land. Property in land is thus very close to the ideal abstraction of absolute real private property where owners have total control over land. For all its exceptional integration into the global economies of oil and long-distance labour migration, Lebanon exemplifies what Samir Amin has described as the fate of the third-world: political environmental pillage (Amin, 2004, pp. 29–52).

Comme nous l’avons vu, les transformations sociales dans le village sont liées aux migrations qui ont joué un rôle important dans la formation des classes sociales et l’accumulation du capital. Ces transformations modifient la relation entre les espaces ruraux et urbains et diminuent leurs différences. Le village est aujourd’hui moins le lieu d’une production agricole que celui d’une consommation de biens importés et de production de force de travail pour l’export. Le droit de produire se concentre dans les mains d’intérêts privés ou quasi privés. Les divisions de la propriété sont d’autant plus visibles dans le village. Les propriétaires de vergers et de villas construisent des barrières pour empêcher l’entrée d’« étrangers » sur leurs terres, ce qui réduit les droits d’usage traditionnels comme la chasse ou la cueillette de fruits et de plantes sauvages. L’expansion de ce phénomène et l’étendue de l’urbanisation limitent l’exercice de droits traditionnels des habitants, et jouent un rôle fondamental dans la transformation de la manière dont ces droits s’expriment. Le droit d’utiliser la terre apparaît de plus en plus comme appartenant aux propriétaires privés.

As we have seen, social transformations in the village are interlinked with migration, which has played an important role in class formation and capital accumulation. These transformations modify the relation between rural and urban spaces and diminish the differences between them. The village is today less a place of agricultural production than one of consumption of imported goods and of the production of labour for export. The right to produce becomes consolidated in the hands of private or quasi-private interests. Property divisions are ever more visible in the village. Owners of orchards and villas build fences around their plots to prevent the entry of ‘outsiders’ to their lands, and thus restrict traditional land-use rights such as hunting and gathering of wild fruits and plants. The expansion of this phenomenon and the spread of urbanization limit the exercise of traditional rights of inhabitants and play a fundamental role in the transformation of the way these rights are expressed. The right to use land appears increasingly the property of private owners.

Où cela conduit-t-il le « Droit au Village » ? Nous pourrions affirmer qu’une approche théorique plus radicale aurait besoin de définir un « droit au village » qui ne soit pas parallèle à un « droit à la ville », en façonnant des écologies politiques (sociales et environnementales) et en créant un programme pour un changement d’écologie politique liant le local au global. Cet article n’a pas tenté une telle approche radicale et programmatique, et s’est borné à l’analyse descriptive d’un cas d’étude, dans les termes proposés par la notion de « droit au village ».

So where does this leave the ‘Right to the Village’? We would contend that a more radical theoretical approach would require not developing ‘a right to the village’ parallel to ‘a right to the city’, but modelling political ecologies (social/environmental) and building a programme for political ecological change linking local to global. This paper has not attempted such a radical and programmatic approach but has confined itself to descriptive analysis of one case within the terms proposed by the notion of a ‘right to the village’.

Ainsi, dans un environnement politique très défavorable à un « droit au village », les villageois ont lutté pour deux des éléments qui pourraient composer un tel droit – le logement et l’activité agricole. Les résultats obtenus ne permettent pas le récit d’une victoire. Mais les contradictions de leur lutte servent à éclairer les faiblesses de l’analyse du monde rural par Lefebvre. S’il doit y avoir un « Droit au Village » qui ne soit pas la simple réplique à petite échelle, en un débordement de la Ville, des droits des travailleurs, il doit être construit (comme l’a proposé Lefebvre) sur une réforme agraire. C’est-à-dire qu’il doit reposer sur le droit des villageois et sur leur engagement dans l’œuvre du travail productif avec la nature (et non dans la « maîtrise de la nature ») au travers de l’agriculture, l’élevage, la chasse, et l’intégration d’autres formes de capital et de travail dans cette œuvre. Certes, vu la hétérogénéité physique irréductible de la terre et la profondeur historique de la production et des moyens de subsistance qui marquent les villages du monde (la « vie paysanne traditionnelle » de Lefebvre), ces relations de production, dans toutes leurs différences globales, doivent être aujourd’hui au centre des analyses et des programmes d’écologie politique. Mais si l’on met de côté l’utopie abstraite, un « droit au village » ici et maintenant peut être mis en acte seulement dans les limites spatiales et temporelles de l’histoire politique et culturelle. Ainsi, nous avons mis en lumière des moments où des droits ont été revendiqués, quand le pouvoir organisé des propriétaires terriens, soutenus par l’Etat, fut contesté et que l’accès au logement et à l’agriculture au village fut partiellement obtenu - mais non un « Droit au Village », si ce n’est comme une lumière fuyante dans les rêves des travailleurs.