I'll start with where I come from... I'm from Simonstown originally, even the southern part of Simonstown. Since the 18th century our family has been in Simonstown. So like, my father was working at the dockyard, for the Navy, in Simonstown, for the rest of his life until they were moved to Gugulethu. So I grew up there… As we were kids now, we were mixed with Coloreds, with Indians. So we didn’t play with Whites actually… The shop is only few minutes walk, maybe 10 to 15 minutes to town. So we used to walk by foot to town. You know maybe groceries, mainly we were delivered. So you just pop to the shop and there's delivery at home. So that was the way we live. It was a beautiful life. And, when we were kids that time everything was beautiful and lovely. (Rose, interview du 19/12/2008)

I’ll start with where I come from… I’m from Simonstown originally, even the southern part of Simonstown. Since the 18th century our family has been in Simonstown. So like, my father was working at the dockyard, for the Navy, in Simonstown, for the rest of his life until they were moved to Gugulethu. So I grew up there… As we were kids now, we were mixed with Coloureds, with Indians. So we didn’t play with Whites actually… The shop is only few minutes’ walk, maybe 10 to 15 minutes to town. So we used to walk by foot to town. You know maybe groceries, mainly we were delivered. So you just pop to the shop and there’s delivery at home. So that was the way we live. It was a beautiful life. And, when we were kids that time everything was beautiful and lovely. (Rose, interview from 19/12/2008)

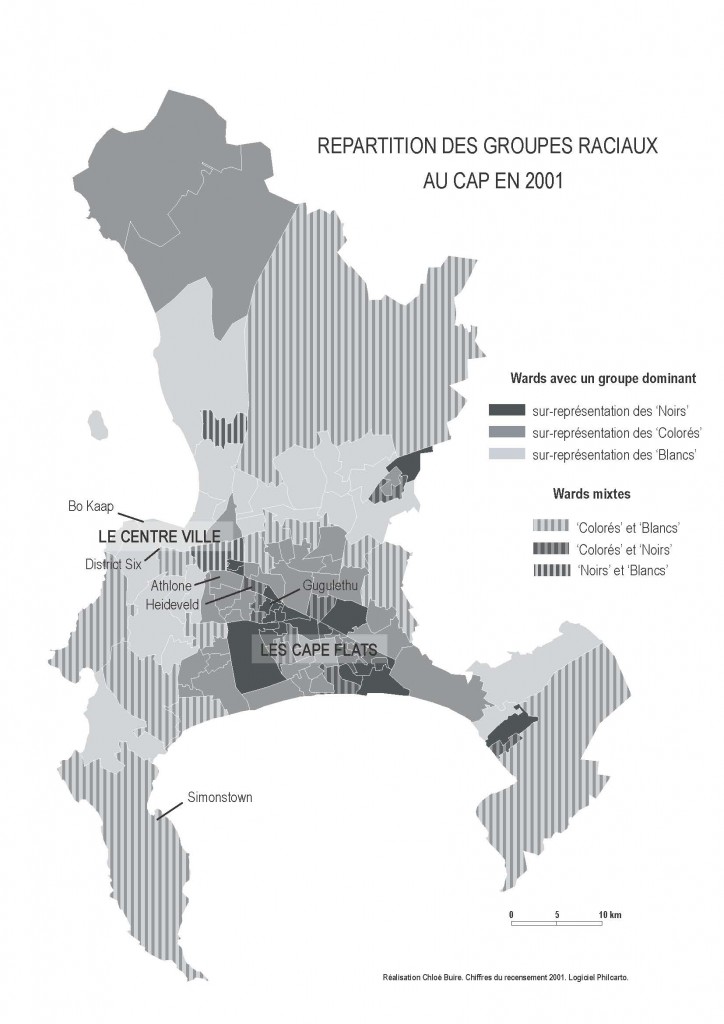

Depuis 1965, Rose habite à Gugulethu, l’un des principaux townships de la ville du Cap, en Afrique du Sud (voir carte 1). Anciennement réservé aux populations dites ‘noires africaines’[1], Gugulethu compte aujourd’hui plus de 80000 habitants, marqués par le chômage et la pauvreté. Le paysage est monotone. Le gouvernement de l’apartheid a construit des rangées de maisons dans des rues en forme de croissant. Ces maisons sont si petites qu’on les appelle "les maisons boîtes d’allumettes" (matchbox houses) et les rues en croissant ont permis d’isoler le quartier du reste de la ville : il n’existe que deux points d’accès pour relier Gugulethu aux axes qui conduisent au centre-ville, à plus de vingt kilomètres de là. La forme urbaine traduit la domination imposée à ceux qui étaient alors appelés les ‘non-Blancs’. En 2008, Rose fait partie d’une petite classe moyenne ‘africaine’ touchée de plein fouet par la flexibilisation accrue du marché du travail. Propriétaire d’une « boîte d’allumettes » qu’elle a héritée de ses parents, Rose vit de ses prestations occasionnelles en tant que cuisinière. Son mari vend des chips et des bonbons aux enfants du quartier depuis le perron. Leur fille cadette prépare son baccalauréat dans un établissement prestigieux, grâce à une bourse privée mais les perspectives restent incertaines. Depuis plusieurs années, les deux fils aînés cumulent les petits emplois sans parvenir à se stabiliser malgré leurs diplômes. Avec Rose, nous avons rapidement sympathisé. J’ai aimé sa gouaille bienveillante. Elle m’a prise sous son aile. Alors en ce début d’été, je me suis rendue chez Rose avec ma caméra pour l’interviewer sur son parcours de vie. Elle m’avait raconté par bribes sa fierté d’être « une vraie capetonienne », « born and bred » dans la métropole. Née en 1950, Rose a connu toutes les phases de l’apartheid et de son démantèlement. J’aimerais qu’elle me raconte son expérience. Et c’est donc ainsi qu’elle commence : « It was a beautiful life ».

Since 1965, Rose has been living in Gugulethu, one of the main townships of Cape Town in South Africa (see Map 1). Formerly reserved for so-called ‘Black African’ populations[1], today over 80 000 residents live in Gugulethu, affected by unemployment and poverty. The landscape is monotonous. The apartheid government built rows of houses in crescent-shaped streets. These houses are so small that they are referred to as ‘matchbox houses’ and the crescent-shaped streets have led to the suburb being isolated from the rest of the city: there are only two access points linking Gugulethu to the city centre, more than twenty kilometres away. The urban shape reflects the domination imposed on those who in those days were called ‘Non-Whites’. In 2008, Rose was part of a small ‘African’ middle class that was fully impacted by increased labour market flexibilisation. Rose is the owner of a matchbox house she inherited from her parents, and lives off her occasional services as a cook. Her husband sells chips and sweets to the children of the suburb from the stoep. While their youngest daughter is currently doing her Matric in a prestigious school, thanks to a private bursary, her prospects remain uncertain. For several years already, the two elder sons have been accumulating small jobs despite their diplomas. Rose and I took to each other immediately. I liked her cheeky but well-meaning humour. She took me under her wing. It was the beginning of the summer and I arrived at Rose’s with my video camera to interview her about her life. She told me in snatches how proud she was of being “a real Capetonian”, born and bred in the metropolis. Rose was born in 1950 and has experienced all the stages of apartheid, from beginning to end. I wanted her to tell me about her experience. And she began like this: “It was a beautiful life.”

Les pages qui suivent s’interrogent sur la fonction sociale de cette image d’un paradis perdu associée à la vie avant l’apartheid. L’idéalisation du passé remplit en effet le rôle d’une utopie à laquelle sont comparées les conditions actuelles. La notion d’utopie est ici utilisée pour désigner les imaginaires qui se construisent en réaction aux injustices vécues au quotidien. Elle ne renvoie donc pas nécessairement à des « non-lieux » particuliers mais plutôt à un processus intellectuel de la situation présente, en particulier à travers les réminiscences nostalgiques du passé. Les représentations idéalisées qui font du pré-apartheid un véritable « paradis perdu » servent alors de mythe[2] fondateur collectif dans le sens où elles permettent de dénoncer à la fois les injustices subies sous l’apartheid et les conditions de vie actuelles dans les townships, mais également dans le sens où elles fondent les discours de réconciliation post-apartheid. À travers la dialectique entre l’utopie du passé et la dystopie encore présente de la ville ségréguée, la dimension spatiale des représentations du juste et de l’injuste est interrogée dans le quotidien des citadins.

In the following pages, I question the social function of the image of lost paradise associated with life before apartheid. Indeed, idealising the past fulfils the role of utopia against which today’s conditions are compared. The notion of utopia is used here to refer to imaginary worlds built in reaction to daily injustice. As such, this notion does not necessarily refer to specific “non-places” but, rather, to an intellectual process of the current situation, particularly through the nostalgic reminiscence of the past. Idealised representations which make of the pre-apartheid era a real “lost paradise”, serve as a collective founding myth[2], in the sense that they make it possible to denounce injustice under apartheid and, at the same time, current life conditions in the townships, but also in the sense that they found post-apartheid reconciliation discourses. Through the dialectics of past utopia and current dystopia which is still present in the segregated city, the spatial dimension of representations of what is fair and unfair is questioned in urbanites’ daily lives.

Après avoir rappelé les liens profonds entre les constructions identitaires citadines et la structure spatiale urbaine dans le contexte sud-africain, je montrerai que la nostalgie avec laquelle Rose se remémore les années qui ont précédé le déménagement forcé imposé à sa famille va au-delà du souvenir personnel. Elle est déjà l’annonce des « cadres sociaux de la mémoire » (Halbwachs, 1925) qui nourrissent des « lignes de fuite » identitaires suivant lesquelles les habitants du Cap construisent des mondes imaginaires qui donnent un sens aux réalités intolérables du quotidien.

After reminding the reader of the close links between urban identity constructions and urban spatial structure in the South African context, I will show that Rose’s nostalgia in remembering the time before the forced removal of her family, goes beyond personal memories, and is a precursor of “social memory frameworks” (Halbwachs, 1925) underlying identity “escape routes” according to which Cape Town residents invent imaginary worlds for themselves, allowing them to make sense of everyday’s intolerable realities.

1. La production spatiale des injustices raciales

1. Spatial Production of Racial Injustice

Photographies 1 et 2 : Le centre-ville et les Cape Flats, quand la topographie accentue les différences socio-économiques. Clichés C. Buire

Photos 1 and 2: City Bowl and Cape Flats, when topography emphasises socioeconomic differences. Photos by C. Buire

Ces photographies résument le contraste qui saisit tous les observateurs du Cap, deuxième ville d’Afrique du Sud par son poids tant démographique qu’économique. La forme même de la ville est un véritable archétype des inégalités spatiales. Alors que la majestueuse Montagne de la Table qui domine le centre-ville a récemment reçu le titre de « Nouvelle Merveille de la Nature »[3], le township de Khayelitsha regroupe plus de 400 000 personnes, dont plus des deux tiers vivent dans des logements de fortune auto-construits. Le contraste entre les très riches banlieues et les bidonvilles les plus pauvres est saisissant par son ampleur, mais également par sa relative invisibilité au quotidien. C’est en cela que Le Cap est une ville éloquente pour donner corps à la notion d’injustice spatiale et pas seulement d’inégalités. Les écarts entre les plus riches et les plus pauvres ne relèvent pas seulement de l’inégale répartition des richesses ou des opportunités mais relèvent plus fondamentalement d’être-au-monde opposés. "Ville blanche, vies noires", résumait Myriam Houssay-Holszchuch en publiant sa thèse en 1999. Quinze ans après, la situation semble n’avoir pas beaucoup changé : l’homogénéité raciale des quartiers se reproduit, les inégalités se creusent. Le « miracle » sud-africain perd de son éclat, terni par le ralentissement économique des années 2000 et un climat social marqué par un mécontentement populaire parfois violent. Cette instabilité est instrumentalisée par les différentes factions du parti au pouvoir comme l’ont montré les émeutes qui ont accompagné les procès de leaders tels que Jacob Zuma en 2008 (aujourd’hui président de la République) ou Julius Malema en 2011. L’Afrique du Sud est donc un exemple archétypal non seulement des inégalités mais surtout du sentiment d’injustice, mettant en évidence sa dimension éminemment spatiale. L’exemple de la ville du Cap peut alors fonctionner comme un « instrument d’optique [qui] fonctionne par grossissement, par spectacularisation des phénomènes, par idéaltypisation voire par caricature : c’est justement parce que la ville de Cape Town est parfois si caricaturale que l’on peut y reconnaître des traits trop subtils ailleurs. » (Houssay-Holzschuch, 2010b : 12)

These photos show the sharp contrast between these two areas of Cape Town, the second largest city in South Africa, demographically as well as economically. Even the actual shape of the city is an archetype of spatial inequalities. While the majestic Table Mountain which towers the City Bowl was recently conferred the title of “New7Wonder of Nature”[3], the township of Khayelitsha includes over 400 000 residents, with more than two thirds living in shacks. The contrast between the very rich and very poor suburbs is striking not just because of its extent, but also because of its relative invisibility on a daily basis. It is in this way that Cape Town embodies the notion of spatial injustice and not just inequality. The differences between richest and poorest concern not only the unequal distribution of wealth or opportunities, but also and more fundamentally being in opposite worlds. As summarised by Myriam Houssay-Holszchuch in her thesis in 1999, this is a case of « White city, black lives ». Fifteen years later, it does not look like the situation has changed much: racial homogeneity is being reproduced in the suburbs and inequalities are accumulating. The South African miracle is losing its shine, tarnished by the economic slowdown of the 2000s and a social climate marked by sometimes violent popular discontent. This instability has been exploited by the various factions of the party in power, as testified by the riots during the trials of leaders such as Jacob Zuma in 2008 or Julius Malema in 2011. For this reason, South Africa is an archetypal example not only of inequalities but, and especially, of the feeling of injustice, highlighting its eminently spatial dimension. The example of Cape Town can function as an “optical instrument [which] functions by magnifying, spectacularising, idealtypifying or even caricaturing phenomena: it’s actually because Cape Town is sometimes so caricatured that one can recognise features in it that are too subtle in other cities.” (Houssay-Holzschuch, 2010b: 12)

Empruntant à Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch l’idée d’idéaltypisation, j’utiliserai ici le cas de la ville du Cap comme un exemple de la production spatiale de l’injustice. Depuis l’arrivée des colons européens à la fin du dix-septième siècle jusqu’à l’instauration de l’apartheid dans les années 1950, la ville s’est construite sur le principe d’une séparation physique entre les groupes sociaux. Ce fut d’abord le fort de la compagnie hollandaise qui incarna l’entre-soi des Européens sur cette terre africaine. L’importation d’esclaves parqués dans des quartiers réservés au dix-huitième siècle, la constitution progressive d’un prolétariat ouvrier au dix-neuvième siècle et les obsessions hygiénistes du pouvoir victorien du début du vingtième siècle se sont ensuite succédé pour produire un espace traversé de frontières socio-raciales omniprésentes (Houssay-Holzschuch, 1999 ; Worden, Van Heyningen et Bickford-Smith, 1998 et 1999). Lorsque le gouvernement d’apartheid est élu en 1948, l’idée générale selon laquelle « les normes [d’urbanisme] dépendent de la personne pour laquelle elles sont édifiées »[4] (Houssay-Holzschuch, 2004 : 6) s’était imposée et l’équipement minimaliste préconisé pour les townships était admis. Deux lois publiées en 1950 ont permis la mise en place de la ségrégation systématique. Le Population Registration Act a rendu systématique l’identification raciale de tous les Sud-Africains, le Group Areas Act a assigné des territoires à chacun des groupes ainsi définis. Or Deborah Posel a démontré le raisonnement tautologique de ces lois puisque, au-delà d’une anthropométrie raciste héritée du siècle précédent, ce sont précisément les lieux fréquentés et les conditions matérielles du quotidien qui ont servi de critères d’identification des races :

Borrowing the notion of idealtypification from Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch, I will use at this stage the case of Cape Town as an example of spatial production of injustice. Since the arrival of European settlers at the end of the 17th century until the establishment of apartheid during the 1950s, the city was developed on the principle of physical separation between social groups. This principle was first upheld by the Dutch East India Company. The import of slaves parked in allocated areas during the 18th century, the progressive rise of the working class during the 19th century, and the hygienist obsessions of early 20th century Victorian power succeeded one another to produce a space crisscrossed by omnipresent socio-racial boundaries (Houssay-Holzschuch, 1999; Worden, Van Heyningen & Bickford-Smith, 1998 and 1999). When the apartheid government was elected in 1948, the general idea according to which “[town planning] standards depended on who they were created for”[4] (Houssay-Holzschuch, 2004: 6) had become widespread by then, and the minimalist equipment advocated for townships was accepted. Two laws published in 1950 led to the implementation of systematic segregation: the Population Registration Act which made the racial identification of all South Africans systematic, and the Group Areas Act which allocated territories to each group defined as such. Yet, Deborah Posel showed the tautological reasoning of these laws since, beyond racist anthropometry inherited from the previous century, it was specifically the places where people went and their everyday life material conditions which were used as racial identification criteria:

Les classificateurs déployaient classiquement une batterie de questions afin d’établir un sens spatial de la race des gens : où ils étaient nés, où ils avaient été à l’école, où ils vivaient, où ils avaient grandi, où leurs amis vivaient, où leurs enfants étaient scolarisés, où et avec qui leurs enfants jouaient. Déniant tautologiquement que le mélange racial puisse être désirable, les classificateurs avaient tendance à lire la race d’un individu en fonction du caractère racial dominant de son lieu de résidence et de la communauté de ceux à qui il ou elle s’associait. (Posel, 2001 : 60, je souligne).

Typically, classifiers deployed a battery of questions so as to establish a spatial sense of people’s race: where they were born, where they went to school, where they lived, where they grew up, where their friends lived, where their children went to school, where and with whom their children played. Tautologically denying that racial mixing could be desirable, classifiers tended to read the race of an individual as a function of the dominant racial character of his/her place of residence and the community of those with whom s/he associated. (Posel, 2001: 60, my underlining).

Lorsque le gouvernement attribuait des logements mal isolés, sans latrines ni eau courante aux ‘Bantous’, il tissait une relation de causalité entre la race des individus et le type de logement qui leur convenait. Posel montre que le raisonnement était reproduit dans l’autre sens : la race pouvait être déduite des espaces pratiqués au quotidien. La boucle tautologique de cette association entre espace et appartenance raciale reste au fondement des identités citadines aujourd’hui. Elle permet d’expliquer la permanence des cadres racialisés dans la mesure où nul ne peut se débarrasser de sa spatialité ; puisque tout corps occupe un espace, toute personne fait également partie d’une race.

When the government allocated badly insulated housing devoid of latrines or running water to the ‘Bantus’, it created a causal relationship between the race of individuals and the type of housing suitable for them. Posel showed that the reverse reasoning was also reproduced: race could be deducted from the spaces in which people lived on a daily basis. The tautological loop of this association between space and racial membership remains the basis for today’s urban identities. It explains the permanence of racialised frameworks in so far as no one can get rid of one’s spatiality; since everyone occupies a space, everyone is also part of a race.

Faire du Cap un archétype d’injustice spatiale, ce n’est donc pas seulement pointer les inégalités matérielles qui caractérisent l’agglomération mais affirmer que l’injustice s’inscrit au cœur du jeu des représentations citadines. Pour reprendre le vocabulaire d’Henri Lefebvre, un espace produit revêt en effet trois dimensions complémentaires. L’espace pratiqué au quotidien renvoie à l’espace perçu. L’urbanisation du Cap se fonde sur le cloisonnement de cet espace perçu de sorte que les pratiques de ‘Noirs Africains’ n’interfèrent pas avec celles des ‘Blancs’. Les ‘Colorés’, à mi-chemin de cette hiérarchie, ont été regroupés dans des townships qui ont servi de zones tampons entre ‘Blancs’ et ‘Noirs’. Mais la production d’un tel espace ségrégué a également affecté l’espace conçu et l’espace vécu des citadins. Suivant Henri Lefebvre, l’espace conçu correspond aux représentations de l’espace, en particulier les représentations urbanistiques véhiculées par les gestionnaires et les politiciens depuis des siècles. L’espace vécu quant à lui renvoie aux symboles et aux valeurs intériorisées par les habitants, c’est-à-dire à leurs espaces de représentation.

As such, making of Cape Town an archetype of spatial injustice is not just pointing to material inequalities as characteristic features of urban areas, but asserting that injustice is part of urban representations. Using Henri Lefebvre’s vocabulary, a produced space takes on three complementary dimensions. The space in which people live daily refers to the perceived space. Cape Town’s urbanisation is founded on the compartmentalisation of that perceived space, in such a way that the practices of ‘black Africans’ do not interfere with those of the ‘Whites’. The ‘Coloureds’, half-way through this hierarchy, were grouped together in townships which were used as buffer zones between ‘Whites’ and ‘Blacks’. But the production of such a segregated space also had an impact on the conceived and lived space of urbanites. According to Henri Lefebvre, the conceived space corresponds to spatial representations, particularly town-planning representations which have been conveyed by managers and politicians for centuries. As to the lived space, it refers to symbols and values internalised by residents, i.e. their representational spaces.

Comment rendre compte de la relation dialectique qui lie les espaces perçus, conçus et vécus ? L’histoire de la ségrégation au Cap a conduit à la formalisation de normes collectives particulièrement strictes concernant les espaces perçus assignés à chaque groupe racial. Mais comment ces représentations nourrissent-elles les espaces intimement vécus par les uns et les autres ? Pour apporter des éléments de réponse, cet article repose sur une immersion ethnographique de deux ans au Cap. Les relations personnelles établies sur le terrain seront restituées sous la forme d’entretiens filmés. Trois citadins seront les personnages principaux de ces courtes vidéos. Leurs récits donnent à entendre, mais également à voir et, espérons-le, à ressentir, les éléments-clés de leur relation à la ville. Il devient alors possible de passer de la description de l’espace tel qu’il est conçu dans les documents d’urbanisme à une analyse de la ville comme un espace de représentations (vécu) mis en acte dans les pratiques des citadins (perçu).

How should one account for the dialectical relation linking perceived, conceived and lived spaces? Cape Town’s history of segregation resulted in the formalisation of particularly strict collective standards, concerning the perceived spaces allocated to each racial group. How do these representations fill the spaces in which people lived intimately? In attempting to answer this question, the article relied on a two-year ethnographic immersion programme in Cape Town. Personal relations established on the field will be published in the form of filmed interviews featuring three Capetonians. Their stories will make viewers see, listen and, hopefully, feel the key elements of their relation to the city. It will then be possible to go from the description of space as it is conceived in town-planning documents, to an analysis of the city as a space of representations (lived) acted out in the practices of urbanites (perceived).

2. Fuites nostalgiques : du souvenir personnel à la mémoire collective

2. Nostalgic Escapes: from Personal Recollections to Collective Memory

Dans les vidéos qui suivent, Rose, déjà présentée en introduction est rejointe par son mari Lucas. Leurs souvenirs d’enfance nourrissent une nostalgie profonde au filtre de laquelle leur situation présente semble une chute sociale inéluctable. Le récit d’Eugene est empreint au contraire d’un espoir religieux. Né au centre-ville en 1973, il est arrivé à Heideveld avec ses parents au début des années 1980 et est rapidement entré dans un gang de rue, les Junky Funky Kids (JFK). Les séjours en prison ont assuré sa professionnalisation dans le milieu de la drogue. Blessé à la tête et hospitalisé pendant six mois alors que les JFK étaient décimés, il a finalement « renoncé au monde » selon la rhétorique évangéliste qui régente désormais sa vie. Une génération sépare Eugene de Lucas et Rose. Lui n’a pas connu le Cap avant l’apartheid. Il habite chez sa mère dans une chambre transformée en appartement familial pour sa femme et ses deux enfants. Une frontière raciale se dresse également entre le jeune homme ‘coloré’ et le couple ‘africain’, et même si chacun critique cette catégorisation, les préjugés contre ‘l’autre groupe’ restent forts des deux côtés. Mais en associant ces trois voix citadines par le truchement du montage vidéo, les expériences individuelles sont transformées en récits transmis à celui qui ne les a pas directement vécues. Elles remplissent une fonction mémorielle abstraite où se mêlent en permanence le passé et le présent, l’ici et l’ailleurs, devenant des créations utopiques qui permettent aux habitants des townships d’exprimer leur positionnement citadin actuel. Comment donnent-ils sens aux expériences de violence et d’oppression ? Comment rendent-ils intelligibles, à eux-mêmes et à autrui, les paradoxes de leur quotidien ? L’idée de « lignes de fuite » utilisée par Deleuze (1977) aide à exprimer la fluidité des discours qu’un individu peut tenir sur lui-même.

In the following videos, Rose, who has already been introduced, is joined by her husband Lucas. Their childhood memories are so nostalgic that their current situation appears like an unavoidable social downfall. On the other hand, Eugene’s story is tinged with religious hope. He was born in the city bowl in 1973 and arrived in Heideveld with his parents at the beginning of the 1980s. It was not long before he joined a street gang, the Junky Funky Kids (JFK). His spells in prison ensured his professionalisation on the drug scene. Wounded on the head and hospitalised for six months while the other members of JFK were all killed, he decided to “renounce the world” according to the Evangelical Rhetoric which today governs his life. One generation separates Eugene from Lucas and Rose. Eugene did not know Cape Town before apartheid. He currently lives at his mother’s house in a room which was transformed into a family apartment for his wife and two children. A racial boundary exists also between this young ‘Coloured’ man and the ‘African’ couple, and even if this categorisation is highly criticised, prejudices against ‘the other group’ remain strong on both sides. Thanks to video editing, I was able to transform three individual experiences into stories that could be communicated to those who did not experience them directly. They fulfil an abstract memory function where the here and there, the past and present are constantly being mixed, becoming utopian creations which enable township residents to express their current urban positioning. How do they make sense of their experience of violence and oppression? How do they make the paradoxes of everyday life intelligible for themselves and others? The notion of “escape routes” as used by Deleuze (1977) helps individuals to express a discourse with more fluidity.

(…) j'essaie d'expliquer que les choses, les gens, sont composés de lignes très diverses, et qu'ils ne savent pas nécessairement sur quelle ligne d'eux-mêmes ils sont, ni où faire passer la ligne qu'ils sont en train de tracer : bref il y a toute une géographie dans les gens, avec des lignes dures, des lignes souples, des lignes de fuite, etc. (Deleuze, Parnet, 1977 : 16)

(…) I’m trying to explain that things and people follow very different routes, and that they do not necessarily know which route they’re on, or where the route they’re busy tracing should be going: in short, there is a whole geography going on in people, with strict routes, changeable routes, escape routes etc. (Deleuze, Parnet, 1977: 16)

L’idée de « lignes de fuite » s’oppose à celle de segment et donc de bornage. Il ne s’agit pas de définir des directions claires, mais de parler des échappées que le discours scientifique a bien du mal à saisir. En racontant leur parcours, Lucas, Rose et Eugene naviguent entre plusieurs époques et plusieurs espaces qui constituent alors une « géographie à l’intérieur des gens ». Lorsque Rose parle de Simonstown – un lieu réel qui existe encore à l’heure actuelle, elle parle aussi de son enfance – un temps révolu. Dans ce processus, le lieu réel disparaît derrière des souvenirs maintes fois reconstruits du lieu passé. Simonstown devient un lieu de fiction, utopique. Et les évènements qui y ont effectivement eu lieu à un moment précis ne sont jamais autre chose qu’un point de comparaison par rapport à la vie actuelle, à la vie d’adulte. Eugene le reconnaît lui-même : lorsqu’il me raconte son adolescence dans les Junky Funky Kids, il n’a pas l’impression de parler de sa propre vie. En suggérant que des mécanismes de mise à distance à la fois temporelle et spatiale interviennent dans la reterritorialisation nécessaire des citadins au jour le jour, je ne prétends pas savoir mieux que Rose, Lucas ou Eugene ce qui constitue leur citadinité, mais je suggère des formes de mise en ordre possibles qui reposent sur la transformation des déménagements forcés en mythe fondateur à partir duquel des horizons utopiques se dessinent.

The notion of “escape routes” contrasts with that of segment and, therefore, demarcation. The idea is not to define clear directions, but to speak about escapes which are generally difficult for the scientific discourse to grasp. By talking about their lives, Lucas, Rose and Eugene navigate between several eras and spaces which are like “maps inside people”. When Rose speaks about Simonstown, a real place which still exists today, she also speaks about her childhood, a bygone era. In this process, the real place disappears behind memories of a past place evoked many times. Simonstown has become a place of fiction, a utopian place. The events that did take place there at a specific time, are never anything else but a point of comparison with their current life, their adult life. Eugene actually admits this: when he talks about his adolescence as a member of the Junky Funky Kids, he does not feel like he is talking about his own life. By suggesting that temporal and spatial distancing mechanisms intervene in the necessary reterritorialisation of urbanites on a daily basis, I do not pretend to know better than Rose, Lucas or Eugene what constitutes their urban citizenship, but I suggest possible structuring forms which rely on transforming forced removals into a founding myth giving rise to utopian horizons.

La fuite nostalgique : Transformer le déracinement passé en force pour le futur

Nostalgic Escape: Transforming Past Forced Uprooting for the Future

Vidéo 1 Trauma : Le déracinement comme expérience fondatrice

Video 1 Trauma: Uprooting as Founding Experience

Dans la vidéo 1 ont été sélectionnés les passages où Rose, Lucas et Eugene racontent leur déménagement au moment où le gouvernement a déplacé des centaines de milliers de Capetoniens pour réaliser le plan ségrégué prévu par le Group Areas Act : le centre-ville où vivait Eugene, les quartiers péri-centraux comme Athlone où résidait Lucas ainsi que les noyaux villageois des périphéries comme Simonstown, d’où est originaire Rose, ont été décrétés « zones réservées aux ‘Blancs’ », tous les habitants ‘colorés’ ou ‘noirs’ ont été expulsés et relogés dans les townships (voir Carte 1). Ces déménagements forcés ont commencé dans les années 1950 et se sont prolongés jusqu’au milieu des années 1980, traumatisant ceux qui en étaient victimes et nourrissant un véritable mythe fondateur. Ce traumatisme est devenu un thème majeur de la géographie sud-africaine critique à partir de l’ouvrage de John Western (1981) dans lequel le géographe reconstitue les itinéraires de familles entières forcées à quitter leur logement de Mowbray pour s’installer dans les townships de Manenberg ou Hanover Park.

In the first video, I selected passages where Rose, Lucas and Eugene talk about their removal when the government displaced hundreds of thousands of Capetonians, to carry out the segregation plan provided for by the Group Areas Act: areas like the city bowl where Eugene lived, the peri-central suburbs like Athlone where Lucas lived, as well as the small towns of the peripheries like Simonstown where Rose comes from, were decreed reserved for ‘Whites’”, and all ‘Coloured’ or ‘Black’ residents were evicted and relocated in townships (see Map 1). These forced removals began in the 1950s and went on until the mid-1980s, traumatising their victims and contributing to the creation of a real founding myth. This traumatism became a major theme of critical South African geography, as found in John Western’s publication (1981) in which he pieces together the itineraries of entire families forced to leave their houses in Mowbray, to settle in the townships of Manenberg or Hanover Park.

Au-delà du récit factuel des itinéraires des uns et des autres, les vidéos transmettent également les hésitations, voire les contradictions inhérentes à tout récit de vie. A un premier niveau de lecture, les trois témoignages insistent sur les déclassements sociaux brutaux liés au déménagement forcé. Lucas met l’accent sur la dégradation des conditions matérielles du fait de quitter une maison de sept pièces pour un logement minuscule. Rose évoque le petit bétail de ses parents qui ne pouvait pas être installé à Gugulethu. Lucas et Rose décrivent donc plus qu’un changement de maison. Leur environnement entier a basculé. Pour ces enfants habitués à un groupe social uni, les townships représentaient des no man’s land austères où chacun était livré à lui-même. Même pour Rose qui a fait partie des quelques milliers de familles ‘privilégiées’ qui ont bénéficié d’un logement en dur dès les années 1960, les réalités matérielles de cette nouvelle vie ont entamé le sens de la dignité personnelle. Elle évoque en particulier avec force détails l’équipement sanitaire des matchbox houses où les toilettes étaient un simple trou ‘à la turque’, situé au fond de la cour et souvent partagé par plusieurs familles. Rose le dit elle-même, à quinze ans, elle n’avait pas encore réalisé la nature du régime de son pays, mais la matérialisation de l’idéologie raciste dans ces maisons d’apartheid a été une confrontation directe à l’injustice.

Beyond the factual account of the interviewees’ itinerary, the videos also communicate moments of hesitation and even contradiction inherent to any life story. A first level of reading shows that the three testimonies insist on the fact that the forced removals brought a brutal drop in social status. Lucas emphasised the degradation of material conditions due to the fact that he had to leave a seven-room house for a small accommodation. Rose evoked her parents’ small cattle that could not be accommodated in Gugulethu. As such, Lucas and Rose described more than a change of residence. Their whole environment changed dramatically. For them, as children, who were used to a unified social group, the township represented an austere no man’s land where they were left to their own devices. Even for Rose who was part of a few thousands of ‘privileged’ families who benefitted from a permanent house from the 1960s already, the material realities of this new life harmed her dignity. She evokes in detail the sanitary installations of the matchbox houses in particular, where toilets consisted of a simple long drop situated in the back yard, and which often had to be shared with several families. While Rose admits that, at fifteen, she still had not grasped the nature of the South African regime, the materialisation of racist apartheid ideology as found in the government’s matchbox houses, brought her face to face with injustice.

Dans le détail pourtant, certains épisodes discordent timidement et invitent à plus de nuances. Lucas par exemple, qui résume d’abord son parcours au passage d’un sept- à un trois-pièces, explique en fait qu’il a d’abord habité une baraque à Nyanga pendant une dizaine d’années. Entre son expulsion d’Athlone et son installation dans une maison en dur, il a donc connu le bidonville, et y a tissé, malgré tout, de nouveaux liens. Les rompre a constitué un nouveau déchirement, même s’il s’agissait alors d’accéder à de meilleures conditions de vie dans une maison en dur. Les déménagements forcés ne sont donc pas une rupture circonscrite séparant la vie d’avant dans les grandes maisons des quartiers mixtes et la vie des townships, dans les petites maisons sous-équipées. Il existe des situations intermédiaires, des parcours accidentés qui incluent des séjours dans les suburbs (en particulier pour ceux employés comme domestiques), dans les bidonvilles (comme c’est le cas pour Lucas), ou encore en dehors du Cap (beaucoup d’enfants ‘africains’ nés en ville ont été confiés à leur famille élargie dans les bantoustans les plus proches ; les enfants ‘colorés’ étaient souvent envoyés dans les fermes aux alentours du Cap). Dans certains itinéraires enfin, le déménagement dans les lotissements de l’apartheid a représenté une véritable amélioration des conditions de vie. C’est le cas d’Eugene. Il ne parle pas de son déménagement à Heideveld comme d’une expulsion raciste mais avant tout comme d’une trajectoire collective qu’il n’y a pas lieu de remettre en question. « Les maisons de Bo Kaap ont été vendues, les gens sont partis à Heideveld. » A propos de sa maison de Bo Kaap, il peine à en reconstituer le nombre d’occupants. Il parle de chambres occupées par des familles entières et de conditions d’hygiène déplorables. Il cite le robinet unique placé dans la cour qui servait alors autant de cuisine que de salle de bain. Ce que Rose reproche au township, Eugene le déplore à propos de Bo Kaap. Mais comme Rose, il décrit le vide des Cape Flats, les immeubles plantés ça et là, comme insensibles à l’idée même de tissu urbain. Pour lui, l’installation à Heideveld fut une condamnation sociale : une fois « dans le ghetto », il n’avait pas d’autre option que d’entrer dans un gang.

Yet, on closer examination, certain episodes are in slight conflict and call for more details. Lucas for instance, who at first talked about moving from a seven- to a three-room house, explains that, in fact, he first lived in a shack in Nyanga for about ten years. Between his eviction from Athlone and his settlement in a permanent house, he experienced life in an informal settlement and, in spite of everything, had forged new relationships there. Breaking these ties constituted for him a new heartrending experience, even if it meant accessing better life conditions in a permanent house. As such, a forced removal is not a defined break, separating one’s former life in a large house in mixed suburbs from one’s new life in a township, in a small under-equipped house. There are intermediate situations with obstacle courses including time spent in the suburbs (those employed as domestic workers in particular), in informal settlements (as was the case for Lucas), or still outside Cape Town (many ‘African’ children born in the city were sent to extended families in the closest Bantustans; ‘Coloured’ children were often sent to farms around Cape Town). Finally, for some, moving into apartheid lots did represent a real life condition improvement. This was the case of Eugene who does not talk about his move to Heideveld as a racist eviction but, above all, as a collective path that does not need to be called into question. “The houses in Bo Kaap were sold, people went to Heideveld.” Concerning his Bo Kaap house, he struggled to remember the number of people who lived in it. He spoke of bedrooms occupied by entire families and of deplorable hygienic conditions. He mentioned the unique tap placed in the yard that served as a kitchen as well as a bathroom. What Rose resents about townships, Eugene resents about Bo Kaap. However, like Rose, he describes the emptiness of the Cape Flats and the fact that buildings were stuck here and there, without taking the urban fabric into consideration. For him, settling in Heideveld was being condemned socially: once “in the ghetto”, he had no other option but to become a gang member.

Finalement, au-delà de leur expérience personnelle, les récits de Rose, Lucas ou Eugene tissent la trame d’un récit collectif qui met l’accent sur le déracinement plutôt que sur les nuances des épisodes successifs qui ont permis, bon an mal an, une adaptation, voire une appréciation positive de certains changements. Ils reconstruisent a posteriori le traumatisme collectif. Plus encore, ils ont eux-mêmes intégré la dimension spectaculaire de leur expérience, élaborant ce que je propose d’appeler des citadinités « martyres »[5]. C’est ce que montre en particulier la vidéo 2 qui insiste sur la distance que les citadins établissent avec leur propre vécu. L’idée de « martyr » rend compte du statut accordé à la souffrance dans les récits citadins : non seulement elle est acceptée, mais elle est même parfois revendiquée.

In the end, beyond their personal experience, the accounts of Rose, Lucas or Eugene are a collective story which accentuates uprooting rather than the differences found in the successive episodes which, year in year out, led to their adapting to certain changes or even appreciating them. They rebuilt the collective trauma a posteriori. In fact, they included of their own accord the spectacular dimension of their experience, elaborating what I propose to call “martyred”[5] urban citizenship. This is what the second video shows in particular, insisting on the distance urbanites establish with their own lived experience. The idea of “martyr” accounts for the status given to suffering in the stories of urbanites: not only is it accepted but sometimes also claimed.

Vidéo 2 : « It’s also nice to experience a little bit of suffering », récits de citadinités « martyres »

Video 2: “It’s also nice to experience a little bit of suffering”, stories of “martyred” urban citizenship

Dans cette seconde vidéo, certaines tournures narratives dépassent le vécu personnel et reproduisent des anecdotes et des remarques élaborées par d’autres. Ainsi lorsque Lucas récite la parabole du voyageur traité selon les canons de l’ubuntu[6] ou lorsque Eugene évoque la démission parentale qui l’a mené à la délinquance, l’intertextualité de leur discours apparaît. C’est cette élaboration d’une histoire collective fondée sur le traumatisme qui caractérise le principe dystopique du récit des déménagements forcés, devenus le symbole abstrait de l’injustice. D’un côté, Lucas emprunte à un discours général de réconciliation en reprenant l’idée d’ubuntu qui était au cœur de la rhétorique utilisée par l’archevêque Desmond Tutu lors des travaux de la commission Vérité et Réconciliation[7]. De l’autre, Eugene répète les clichés paternalistes du gouvernement de l’apartheid lorsqu’il évoque la démission parentale et l’alcoolisme généralisé. Ce n’est donc pas le contenu, plus ou moins progressiste des discours empruntés qui est en jeu, mais avant tout l’opération par laquelle des bribes de phrases toutes faites viennent appuyer la narration de l’expérience personnelle. Ce serait donc la mise en récit qui contribuerait au passage de « la multiplicité des souvenirs de l’expérience à l’unicité d’une mémoire dite "collective" » (Lavabre, 2007 : § 17). Dans tous les cas, l’idée du traumatisme collectif est intériorisée, voire revendiquée comme preuve d’une certaine authenticité citadine. Murray et al. proposent ainsi de faire de la victime des déménagements forcés « la figure emblématique des citadins du Cap »[8] (Murray et al., 2008 : 14).

In the second video, some of the stories go beyond personal experience as they recount anecdotes and remarks made by others. As such, when Lucas recites the parable of the traveller who is welcomed in true ubuntu[6] fashion, or when Eugene evokes the abdication of parental responsibility which led him to do crime, there is intertextuality. It is the elaboration of a collective history founded on trauma which characterises the dystopian principle of stories about forced removals, which have become the abstract symbol of injustice. On the one hand, Lucas borrows from a general discourse of reconciliation by reusing the ubuntu concept which was central to Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s rhetoric during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission[7]. On the other hand, Eugene repeats the paternalistic clichés of the apartheid government when he evokes the abdication of parental responsibility and generalised alcoholism. It is not so much the more or less progressive content of borrowed discourses which is at stake, but the operation through which pieces of ready-made sentences come to support the narration of their personal experience. The way the story is put together could be what contributes to the passage from “the multiplicity of experience memories to the uniqueness of a so-called ‘collective’ memory” (Lavabre, 2007: § 17). In all cases, the idea of collective traumatism is internalised or even claimed as evidence of a certain urban authenticity. As such, Murray et al. propose to make of the victim of a forced removal “the symbolic urban figure of Cape Town”[8] (Murray et al., 2008: 14).

L’exemple du Cap permet donc d’approfondir la notion d’injustice spatiale en montrant comment le racisme informe tout le processus de production de l’espace et pas seulement le cadre matériel de la ville. Pour ce qui est de l’espace conçu, les normes urbanistiques renforcent les préjugés autant qu’elles s’en inspirent. En ce qui concerne l’espace vécu, les souffrances vécues au niveau individuel nourrissent le récit d’un traumatisme collectif, qui sert lui-même de trame à la mise en mots des itinéraires personnels. L’espace perçu quant à lui est sans cesse reproduit par des pratiques spatiales conditionnées par les codes raciaux. La discussion porte alors sur la possibilité de surmonter la description des injustices spatiales et d’imaginer de nouvelles façons de penser l’espace. Dans leur ouvrage collectif sur les imaginaires du Cap après l’apartheid, Sean Field et al. attribuent une valeur thérapeutique au « mythe » populaire : « Les mythes culturels populaires remplissent des fonctions diverses, tant positives que négatives, mais le plus notable est qu’ils fournissent aux gens le vocabulaire et les croyances pour comprendre et relever la foule de défis qui traversent la ville. » (Field, et al., 2007 : 11). A considérer le récit du traumatisme lié au déménagement forcé comme un mythe fondateur des citadinités, il est alors possible d’ouvrir de nouvelles perspectives à la production de l’espace urbain en s’appuyant sur les « lignes de fuite » des imaginaires citadins depuis la fin de l’apartheid.

The example of Cape Town makes it possible to examine the notion of spatial injustice in more detail, by showing how racism informs the entire space production process and not only the material framework of the city. Concerning conceived space, town-planning standards reinforce and draw inspiration from prejudices. Concerning the lived space, the suffering experienced at individual level contributes to the story of a collective trauma, which in turn serves as framework for putting personal itineraries into words. As to perceived space, it is constantly reproduced by spatial practices conditioned by racial codes. The discussion is about the possibility of overcoming the description of the forms of spatial injustice, and imagining new ways of looking at space. In their collective work on Cape Town’s post-apartheid imagined worlds, Sean Field et al. give popular myths a therapeutic value: “Popular cultural myths fulfil various functions, positive as well as negative, but of note is the fact that they give people the vocabulary and beliefs to understand and take up the myriad of challenges found in the city.” (Field et al., 2007: 11). When considering trauma accounts linked to forced removals as a founding myth of urban citizenship, it is then possible to open new perspectives for the production of urban space by relying on the “escape routes” of urban imagination since the end of apartheid.

Construction d’un mythe fondateur partagé

Creating a Shared Founding Myth

La première ligne qui caractérise les expériences citadines du Cap aujourd’hui est liée à une fuite temporelle dans l’idéalisation nostalgique de la ville avant l’apartheid. Les voyageurs du dix-huitième siècle avaient surnommé Le Cap « la taverne des océans ». Ce mythe du cosmopolitisme originel a ressurgi dans le romantisme des quartiers populaires des années 1950. Sophiatown à Johannesburg ou District Six au Cap sont devenus les emblèmes d’un âge d’or de la citadinité en Afrique du Sud, brutalement balayé par l’apartheid. Au Cap, le musée de District Six illustre comment les déménagements forcés nourrissent désormais un véritable mythe fondateur.

The first characterisation of urban experience in Cape Town today is linked to a temporal escape into the nostalgic idealisation of the city before apartheid. During the 18th Century, travellers nicknamed Cape Town “the Tavern of the Oceans”. This myth of original cosmopolitanism resurfaced in the romanticism of popular areas during the 1950s. Sophiatown in Johannesburg or District Six in Cape Town became symbolic of a golden urban citizenship age in South Africa, which was brutally swept away by apartheid. In Cape Town today, the District Six Museum illustrates how forced removals contribute to the founding myth.

Le musée est né de la mobilisation des anciens résidents après leur expulsion du quartier de District Six. Dans les années 1980, les bulldozers de l’apartheid avaient dégagé un vaste terrain au sud du centre-ville, aujourd’hui rebaptisé Zonnebloem. Mais un comité de soutien a œuvré à préserver la mémoire de District Six. En 1994, une exposition a été organisée dans une église abandonnée pour célébrer la vie du quartier avant sa destruction. À partir de photographies et d’objets prêtés ou donnés par les habitants, cette exposition avait un but à la fois culturel et scientifique (informer le public, local et international), politique (faire pression pour la restitution des terrains grâce aux lois de réconciliation), voire thérapeutique (offrir un espace d’expression aux anciens résidents, notamment en soutenant l’écriture d’autobiographies ou en formant des guides de musée). Dans la forme comme dans le contenu, l’exposition a eu tant de succès qu’elle a fini par devenir la collection permanente d’un musée aujourd’hui reconnu dans le monde entier pour son rôle dans la construction d’une nouvelle société[9]. L’ancienne église méthodiste, située à la bordure du centre ville et à l’entrée de ce qui fut District Six, est devenue un lieu de mémoire qui participe à la sacralisation du « symbole perdu de l’urbanité capetonienne » (Houssay-Holzschuch, 2010 : 113). Aujourd’hui, la référence à District Six évoque donc à la fois l’ancien quartier péricentral disparu et le musée de la réconciliation valorisant les souvenirs individuels pour construire une mémoire collective. Cette capacité à matérialiser l’absence et à convoquer le passé dans le présent est revendiquée par les initiateurs du musée eux-mêmes. Leur brochure cite Valmont Layne, le directeur : « Je pense que nous avons besoin de construire une communauté qui réponde à l’idée de District Six. Et je dis "l’idée" à dessein parce que nous ne sommes pas en train de reconstruire District Six. Nous prenons l’idée de District Six et nous l’appliquons à de nouvelles circonstances. Il faut donc de l’innovation autant que de la réflexion sur le passé. »

The Museum arose from the mobilisation of former residents after their eviction from the suburb of District Six. During the 1980s, the bulldozers of apartheid cleared a vast land south of the city centre, which was later renamed Zonnebloem. But a support committee worked towards preserving the memory of District Six. In 1994, an exhibition was organised in an abandoned church to celebrate life in the suburb before its destruction. Based on photographs and objects lent or donated by residents, the objective of the exhibition was cultural as well as scientific (i.e. to inform the local and international public), political (i.e. to put pressure on the government to return these lands to their original owners thanks to reconciliation laws), and even therapeutic (i.e. to offer a space for expression to former residents, particularly by supporting the publication of autobiographies or training museum guides). In form and content, the initial exhibition was so well received that it ended up becoming permanently part of the District Six Museum collection, which today is acknowledged worldwide for its role in building a new society[9]. The former Methodist church, which is situated on the border of the city centre and at the beginning of what would have been District Six, has become a place of memory involved in making “the lost symbol of Capetonian urban citizenship” sacred (Houssay-Holzschuch, 2010: 113). Today, the reference to District Six evokes the old pericentral suburb which disappeared and the museum of reconciliation which enhances individual memories to build a collective memory. This capacity to materialise what is absent and to invoke the past into the present, is claimed by the actual Museum initiators. Their brochure quotes Museum Director Valmont Layne: “I think that we need to build a community that can satisfy the District Six concept. And I used « concept » on purpose to mean that we are not rebuilding District Six. We take the District Six concept and we apply it to new circumstances. In this light, we need innovation as much as reflecting back on the past.”

Le musée du District Six est donc l’exemple d’un véritable géo-symbole[10] capable de porter à la fois plusieurs types de discours, servant diverses causes et représentant divers publics. Cette perméabilité est certainement la clé de sa réussite. Le musée n’est pas une vitrine immuable mais une véritable performance, c’est-à-dire une expérience individuelle lors de laquelle le mythe fondateur attaché à District Six est réalisé du fait même d’être énoncé. Cette matérialisation du mythe est au cœur du lien établi par Joël Bonnemaison entre mythe et territoire :

The District Six Museum illustrates a real geosymbol[10] which can underlie several types of discourses at the same time, serving various causes and representing various publics. This permeability is certainly key to its success. The Museum is not an unchanging showcase but a real performance, i.e. an individual experience during which the founding myth attached to District Six is materialised by the very mention of it. Myth materialisation is central to the link Joël Bonnemaison establishes between myth and territory:

(…) la lecture d’un mythe n’est pas seulement littéraire ou structurale : elle devient aussi spatiale. La géographie des lieux visités par le héros civilisateur, le saint ou le gourou, les itinéraires qu’il a parcourus, les endroits où il a révélé sa puissance magique, tissent une structure spatiale symbolique qui met en forme et crée le territoire. Cette géographie sacrée donne au "mythe fondateur" sa pesanteur : elle l’incarne dans une terre et le révèle en tant que geste créateur de société. (Bonnemaison, 1981 : 254)

(…) reading a myth is not just literary or structural, it is also spatial. The mapping of places visited by the civilising hero, the saint or the guru, the paths he followed, the places where he revealed his magical power, create a symbolic spatial structure which shapes and creates the territory. This sacred mapping gives weight to the « founding myth », incarnating it in a territory and revealing it as a gesture creating society. (Bonnemaison, 1981: 254)

L’expérience du musée de District Six est donc l’équivalent de cette « lecture spatiale » du mythe fondateur, si l’on accepte quelques adaptations. Le contenu même du mythe, au lieu d’être une genèse territoriale est le récit d’une déterritorialisation. Les itinéraires qui « mette[nt] en forme et crée[nt] le territoire » sont moins des pèlerinages (bien que l’on puisse considérer les promenades organisées dans les ruines du District Six comme tels) que des expulsions. Enfin le musée fait du lieu du mythe une mise en scène du mythe lui-même. Autant d’ambiguïtés qui aident à comprendre la notion d’utopie.

As such, the experience of the District Six Museum is equivalent to the “spatial reading” of the founding myth, on accepting a few adaptations. The actual content of the myth, instead of being a territorial genesis, is the story of a deterritorialisation. Itineraries which “shape and create the territory” are not so much pilgrimages (although the organised tours in the ruins of District Six could be perceived as such) as evictions. In the end, the Museum makes of the mythical place a staging of the actual myth; as many ambiguities which help us to understand the notion of utopia.

L’utopie est caractérisée par une double étymologie, comme le soulignait Thomas More dès l’en-tête de l’édition de 1518 de son ouvrage éponyme qui a marqué l’entrée du terme dans la langue courante. Le mot utopie est formé sur la racine grecque topos, le lieu, auquel est ajouté un préfixe de négation, oú- en grec. Ou-topos désigne donc ce qui n’a pas de lieu, ce qui ne se trouve nulle part. Mais More fait remarquer qu’une fois transformé en u-, le préfixe peut renvoyer à l’adverbe eu, qui signifie « bien » ou « justement ». Il orthographie alors « utopie » sous la forme Eutopia en suggérant qu’il s’agit là non plus seulement d’un lieu fictionnel mais également du « lieu du Bien », du « lieu de justice ».

Utopia is characterised by a double etymology, as highlighted by Thomas More in the header of the 1518 edition of his work of the same name which marked the entry of the word in everyday language. The word ‘utopia’ is made up of the Greek root topos which means “place”, prefixed with the Greek negation oú. As such, ou-topos refers to “what does not take place”, “that which is found nowhere”. More points out that, once transformed in u-, the prefix can also refer to the adverb eu which means “good” ou “fairly”. He spelled ‘utopia’ as Eutopia, suggesting that this is no longer about a fictional place only, but also about “a place of Good”, “a place of justice”.

Idéalisation du lieu disparu, incarnation du mythe fondateur, célébration du passé pour imaginer le futur, District Six est donc un exemple du potentiel utopique de la mémoire mise en scène par la muséographie. Or, un musée n’est pas seulement un discours, c’est également une entreprise ancrée dans la conjecture économique et surtout politique d’un territoire. Le discours de réconciliation porté par les fondateurs du musée ne peut pas être tout à fait compris s’il n’est pas relié au contexte plus général de la construction nationale sud-africaine depuis 1994.

District Six as the idealisation of the vanished place, the incarnation of the founding myth or the celebration of the past to imagine the future, is an example of the utopian potential of memory staged by the museography. Yet, a museum is not a discourse only; it is also an undertaking which is rooted in the economic and especially political conjecture of a territory. The reconciliation discourse of the Museum founders cannot be quite understood unless it is linked to the more general context of South African nation building since 1994.

Le musée de District Six affirme poser les bases d’une société à venir. Le mythe fondateur du déracinement imposé par l’apartheid a une fonction cathartique. L’injustice spatiale, une fois dénoncée, peut être dépassée et les Capetoniens du vingt-et-unième siècle seront capables de retrouver un cosmopolitisme d’autant plus stable et serein qu’ils auront tiré les leçons de leur passé. Ce discours de réconciliation est omniprésent aujourd’hui en Afrique du Sud dans des expressions telles que « la Nouvelle Afrique du Sud » ou « la Nation arc-en-ciel ». L’élection de Mandela aurait ouvert une nouvelle ère, profondément anti-raciste et humaniste. Il faut pourtant dépasser ces grandes déclarations et prendre la mesure des multiples inflexions politiques qui sous-tendent ladite « transformation » sud-africaine. Les statistiques démentent l’avènement d’une société plus égalitaire. Au début des années 2010, le thème de la désillusion dépasse celui du miracle dans les discours tant populaire que sociologiques (Gibson, 2011).

The District Six Museum declares that it is putting down the foundations of tomorrow’s society. Indeed the founding myth of uprooting imposed by apartheid had a cathartic function. Spatial injustice once denounced can be transcended, and 21st Century Capetonians will be able to find a cosmopolitism all the more stable and serene since they will learn from their past. This reconciliation discourse is omnipresent in South Africa today, in expressions such as “the New South Africa” or “the Rainbow Nation”. While Mandela’s election opened up a new highly anti-racist and humanitarian era, we need to move beyond these grand declarations and adopt the multiple political inflexions which underlie the so-called South African “transformation”. Statistics refute the advent of a more egalitarian society. At the beginning of the 2010s, disillusion has been stronger than miracles in the popular as well as sociological discourses (Gibson, 2011).

La période post-apartheid a été marquée par une relation duale à la mémoire. D’un côté, le processus de réconciliation, de construction nationale et d’abolition de la séparation raciale a initié une rupture définitive avec le passé. De l’autre, une forme de ressentiment exprime la reconnaissance douloureuse et plus ambivalente de combien le passé est encore profondément présent à travers le racisme, les inégalités et les préjugés. (Fassin, 2007 : 312)

The post-apartheid period was marked by a dual relation to memory. On the one hand, the process of reconciliation, nation building and abolition of racial separation initiated a definitive break with the past. On the other hand, a form of resentment expresses the painful and more ambivalent acknowledgement of how the past is still deeply present through racism, inequalities and prejudices. (Fassin, 2007: 312)

Dans un article non publié à ce jour, Philippe Gervais-Lambony et Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch soulignent ainsi que « le passé ne renvoie plus seulement au passé de l’apartheid et du pré-apartheid, mais également aux premiers temps du post-apartheid » (Gervais-Lambony et Houssay-Holzschuch, sans éditeur : 13). Les discours se multiplient, qui expriment une certaine nostalgie de la vie sous l’apartheid, et surtout une nostalgie « pour les espoirs et les enthousiasmes des années 1990 » (ibid.). Le « miracle » sud-africain s’effrite donc et le monde utopique promis au lendemain des élections de 1994 peine désormais à contenir l’impatience de la majorité qui constate, jour après jour, la reproduction, non seulement des inégalités, mais aussi des humiliations qui avaient été pour un temps rangées parmi les souvenirs d’un temps heureusement révolu.

In an unpublished article, Philippe Gervais-Lambony and Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch highlight the fact that “the past no longer only refers to the past of apartheid and pre-apartheid, but also to the beginning of post-apartheid” (Gervais-Lambony and Houssay-Holzschuch, unpublished: 13). We are seeing an increase in the number of discourses on nostalgia about life under apartheid, and more particularly nostalgia “about the hope and enthusiasm of the 1990s” (ibid.). The South African miracle is chipping away and, today, the post-1994 promise of a utopian world can barely contain the impatience of the majority which finds that, day after day, inequalities and the humiliation which for a while had been placed on the shelf of a fortunately bygone era, are being reproduced.

Le Cap offre un exemple de ville où l’injustice a nourri des lignes de fuite temporelle et spatiale qui associent des lieux disparus et leurs reconstitutions symboliques, les souvenirs personnels et la mémoire collective, l’idéalisme intellectuel et les discours institutionnels. Le projet du musée de District Six rappelle que la construction d’un discours général sur ce que pourrait être « la ville juste » ne va pas sans poser de questions éthiques et politiques. Afin de mettre en évidence la délicate position du chercheur qui est confronté à ces discours à plusieurs niveaux, je m’arrêterai sur le personnage d’Eugene. Ses souvenirs mêlant la prison et la conversion montrent comment se construisent de véritables mondes parallèles dans lesquels la vie quotidienne est « remise en ordre ».

Cape Town exemplifies the city where injustice promoted temporal and spatial escape routes, associating bygone places with their symbolic reconstructions, personal memories, collective memory, intellectual idealism and institutional discourses. The District Six Museum project reminds us that building a general discourse on what could be “a fair city” lead to asking ethical and political questions. In order to show the delicate position of researchers confronted with multi-levelled discourses, I will consider Eugene whose mixed memories of prison and conversion show how parallel worlds can be built, and in which daily life is “restored to order”.

3. Fuites hétérotopiques : du gang à l’église, les mondes parallèles d’Eugene

3. Heterotopic Escapes: From Gang to Church, Eugene’s Parallel Worlds

Depuis le début du vingtième siècle, une législation paternaliste a mis en place des services sociaux exclusivement destinés aux ‘Colorés’ qui étaient considérés comme une race « dégénérée » particulièrement sujette à l’alcoolisme et à la perte des valeurs familiales (Adhikari, 2005 ; Jensen, 2008). L’une des conséquences de ces politiques a été un taux d’emprisonnement record chez cette population. Aujourd’hui encore, la prison fait partie des espaces de représentations largement partagés par les habitants des townships ‘colorés’, indépendamment de leur expérience effective de ce lieu. Reprenant les réflexions de Michel Foucault sur les hétérotopies, je montrerai que la prison, berceau des gangs constitue un de ces « lieux hors de tous les lieux » où s’inventent des utopies permettant de restaurer une certaine rationalité pour des individus en rupture avec le monde réel. L’Eglise, et en particulier les formes les plus prosélytes de l’évangélisme protestant devient alors le double chrétien à cette fuite hors du monde, ultime phase du disempowerment des opprimés et contre-modèle de pensée de l’activisme.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, a paternalistic legislation has been implementing social services intended exclusively for ‘Coloureds’ who were considered as a race of “degenerates”, subjected in particular to alcoholism and the loss of family values (Adhikari, 2005; Jensen, 2008). One of the consequences of these policies has been the record imprisonment rate among this population. Today still, prison is part of the representation spaces largely shared by the residents of Coloured townships, independently of their actual experience of prison. Referring to Michel Foucault’s thoughts on heterotopies, I will show that prison, as the cradle of gangs, constitutes one of these “places outside of all places” where utopias are being invented, and make it possible to restore a certain rationality for individuals at odds with the real world. The Church and the most proselytic forms of Protestant Evangelism in particular, offer a very potent means of escaping the world, the ultimate phase of disempowerment of the oppressed and a counter-model of activist thought.

Le rôle des hétérotopies : « je recommence à me reconstituer là où je suis » (Foucault, 1984)

The Role of Heterotopias: “I begin again […] to reconstitute myself there where I am.” (Foucault, 1984)

Il y a également, et ceci probablement dans toute culture, dans toute civilisation, des lieux réels, des lieux effectifs, des lieux qui sont dessinés dans l'institution même de la société, et qui sont des sortes de contre-emplacements, sortes d'utopies effectivement réalisées dans lesquelles les emplacements réels, tous les autres emplacements réels que l'on peut trouver à l'intérieur de la culture sont à la fois représentés, contestés et inversés, des sortes de lieux qui sont hors de tous les lieux, bien que pourtant ils soient effectivement localisables. Ces lieux, parce qu'ils sont absolument autres que tous les emplacements qu'ils reflètent et dont ils parlent, je les appellerai, par opposition aux utopies, les hétérotopies (Foucault, 1994 [texte original de 1967, première publication 1984] : 47)

There are also, probably in every culture, in every civilization, real places – places that do exist and that are formed in the very founding of society – which are something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. Places of this kind are outside of all places, even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality. Because these places are absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about, I shall call them, by way of contrast to utopias, heterotopias. (Foucault, 1994 [original text from 1967, first publication 1984]: 47 – Translated by Jay Miskowiec)

Avec le terme d’ « hétérotopie » Foucault rend possible l’existence de lieux à la fois « absolument réels et absolument irréels » dont les exemples clés vont de la prison, lieu emblématique de la pensée foucaldienne, aux plus surprenants saunas scandinaves, en passant par les bibliothèques et les musées, ce qui n’est évidemment pas sans faire écho au présent exposé concernant District Six. Foucault explique le principe de l’hétérotopie à travers la métaphore du miroir.

With the word “heterotopia”, Foucault makes the existence of places “absolutely real” and at the same time “absolutely unreal” possible, with key examples going from the prison which is symbolic of Foucauldian thought, to the more surprising Scandinavian saunas, via libraries and museums, which is obviously not without echoing this article as far as District Six is concerned. Foucault explained the principle of heterotopia through the mirror metaphor.

Le miroir, après tout, c'est une utopie, puisque c'est un lieu sans lieu. Dans le miroir, je me vois là où je ne suis pas, dans un espace irréel qui s'ouvre virtuellement derrière la surface, je suis là-bas, là où je ne suis pas, une sorte d'ombre qui me donne à moi-même ma propre visibilité, qui me permet de me regarder là où je suis absent - utopie du miroir. Mais c'est également une hétérotopie, dans la mesure où le miroir existe réellement, et où il a, sur la place que j'occupe, une sorte d'effet en retour ; c'est à partir du miroir que je me découvre absent à la place où je suis puisque je me vois là-bas. À partir de ce regard qui en quelque sorte se porte sur moi, du fond de cet espace virtuel qui est de l'autre côté de la glace, je reviens vers moi et je recommence à porter mes yeux vers moi-même et à me reconstituer là où je suis ; le miroir fonctionne comme une hétérotopie en ce sens qu'il rend cette place que j'occupe au moment où je me regarde dans la glace, à la fois absolument réelle, en liaison avec tout l'espace qui l'entoure, et absolument irréelle, puisqu'elle est obligée, pour être perçue, de passer par ce point virtuel qui est là-bas. (ibid.)

The mirror is, after all, a utopia, since it is a placeless place. In the mirror, I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface; I am over there, there where I am not, a sort of shadow that gives my own visibility to myself, that enables me to see myself there where I am absent: such is the utopia of the mirror. But it is also a heterotopia in so far as the mirror does exist in reality, where it exerts a sort of counteraction on the position that I occupy. From the standpoint of the mirror I discover my absence from the place where I am since I see myself over there. Starting from this gaze that is, as it were, directed toward me, from the ground of this virtual space that is on the other side of the glass, I come back toward myself; I begin again to direct my eyes toward myself and to reconstitute myself there where I am. The mirror functions as a heterotopia in this respect: it makes this place that I occupy at the moment when I look at myself in the glass at once absolutely real, connected with all the space that surrounds it, and absolutely unreal, since in order to be perceived it has to pass through this virtual point which is over there. (ibid.)

La vidéo qui suit est un exemple de « miroir » posé face à Eugene par le truchement de la caméra. Les souvenirs, souvent allusifs de ses années dans le gang des Junky Funky Kids, racontés à travers la rhétorique évangéliste dans laquelle il donne désormais sens à sa vie illustrent la capacité à « se reconstituer soi même » qui caractérise les hétérotopies.

The following video is an example of a “mirror” placed in front of Eugene via the camera. The memories, often alluding to the years he spent with the Junky Funky Kids, told through the Evangelical rhetoric which today gives meaning to his life, illustrate the capacity to “reconstitute oneself” which is characteristic of heterotopias.

La prison, les gangs : hétérotopie de la violence

Prison and Gangs: Heterotopia of Violence

Vidéo 3 : Eugene, du gang à l’église

Video 3: Eugene – from Gang to Church

Les vétérans racontent invariablement des histoires idéalisées à propos du passé. Ils ne font pas cela simplement pour tourner en dérision ce que la génération actuelle a fait du système des gangs. Ils le font aussi parce que l’emprisonnement est une épreuve humiliante, souvent éprouvante et en construisant le récit de leur vie pour un témoin/chercheur, ils sont inévitablement amenés à restaurer leur dignité. L’interviewé passe sous silence les actes de violence qu’il a commis et omet souvent la violence qui a été commise contre lui. (Steinberg, 2004a : 3)

Veterans invariably tell idealised stories about the past. They do so, not simply to deride what the current generation has done to the Number, but also because imprisonment is a humiliating, often harrowing, experience, and constructing one’s life narrative before a witness/researcher inevitably involves restoring dignity. The interviewee mutes the acts of violence he has committed and often omits the violence committed against him. (Steinberg, 2004a: 3)

La remarque méthodologique faite par Jonny Steinberg en introduction de son étude sur les gangs dans les prisons sud-africaines rappelle que l’exercice même de l’enquête anthropologique est un miroir ouvrant des perspectives à la nostalgie (« histoires idéalisées du passé ») et à l’utopie (« restaurer la dignité »). Ce processus est d’autant plus fort pour un membre de gang (ndota) puisque divulguer les règles et hiérarchies internes de l’organisation est un crime puni par les lois du gang. Il existe en effet une tradition orale complexe venue des groupes errants de bandits qui se sont formés à la fin du dix-neuvième siècle dans la région minière du Witwatersrand (van Onselen, 1982). Parmi ces jeunes hommes déracinés par l’industrialisation brutale de leur environnement, Mzoozepi Mathebula est célèbre sous le nom de Nongoloza. La vie de son armée de hors-la-loi est devenue la base d’une odyssée transmise aujourd’hui encore aux nouvelles recrues des gangs de prison à travers une foule d’actes symboliques qui orchestrent la vie à l’intérieur des cellules. Passages à tabac, viols, attaques à l’arme blanche sur les gardiens ou les membres des gangs rivaux, le code de l’honneur repose sur la capacité à endurer et à accomplir des actes d’une violence extrême pouvant aller jusqu’à la mort, accidentelle lorsqu’elle fait suite à une bagarre, mais parfois également dûment édictée comme sentence par de véritables tribunaux internes au gang. Les gangs reproduisent ainsi la hiérarchie et la violence à laquelle ils sont eux-mêmes soumis à l’intérieur de la prison. Mais cette violence est sublimée par le recours au récit de la vie de Nongoloza, transformé en héros mythologique capable d’exploits surnaturels : il boit du poison en souriant, il se bat jusqu’à avoir du sang à hauteur des chevilles, les balles de fusils ricochent contre sa peau etc.

The methodological remark made by Jonny Steinberg in introducing his research on gangs in South African prisons, is a reminder that anthropological surveys can open up perspectives onto nostalgia (“idealised stories of the past”) and utopia (“restoring dignity”). This process is actually stronger for a gang member (ndota) since revealing a gang’s internal rules and hierarchies is a crime punishable by gang law. There is indeed a complex oral tradition originating from wandering groups of bandits that gathered at the end of the 19th century in the mining region of the Witwatersrand (van Onselen, 1982). Among these young men uprooted by the brutal industrialisation of their environment, Mzoozepi Mathebula was well-known by the name of Nongoloza. The life of his army of outlaws became the basis for an odyssey which is still passed on today to the new prison gang recruits through many symbolic acts orchestrating life inside the prison cells. Beating up, rapes, stabbing wardens or members of rival gangs, the code of honour depends on the capacity to endure and accomplish acts of extreme violence that can lead to accidental death in the case of fights, and sometimes to premeditated death as sentences duly decreed by gang tribunals. As such, gangs reproduce the hierarchy and violence to which they are themselves subjected in prison. Yet this violence is sublimated by resorting to the life story of Nongoloza, who is transformed into a mythological hero able to perform supernatural exploits: he drinks poison while smiling, he fights until he is ankle-deep in blood, gun bullets ricochet off his skin etc.