La justice environnementale est devenue un paradigme incontournable dans les procédures d’aménagement du territoire et de planification aux Etats-Unis (Taylor, 2001). Son cadre d’analyse se référait principalement, à ses débuts, aux impacts disproportionnés des infrastructures polluantes (sites d’enfouissement, usines, autoroutes, etc.) sur les communautés pauvres et/ou appartenant à des minorités ethniques. Il s’étend aujourd’hui à de nombreuses sphères de l’action publique et privée (dès lors que cette dernière nécessite le consentement des pouvoirs publics).

In the United States, Environmental Justice (EJ) has become a major paradigm for regional development and planning (Taylor, 2001). In the beginning, the framework for analysis essentially pointed at the disproportionate impact of polluting infrastructures, such as landfill sites for industrial waste, factories and highways in poor or ethnic minority communities. Today, this framework covers a number of areas who resort to public or private policies (if they need the assent of public authorities).

La contestation des pratiques conduisant à la concentration des problèmes environnementaux dans les communautés les plus fragiles a induit, dans un premier temps, activistes et chercheurs à objectiver leurs observations (Bullard, 1990 ; Cole et Foster, 2001), à mettre au point des grilles d’analyse permettant d’associer les enjeux environnementaux aux enjeux de justice sociale et de ségrégation raciale, ces derniers ayant été traditionnellement exclus des questions environnementales (Theys, 2007). Puis, au fur et à mesure que le mouvement a pris de l’ampleur et une fois qu’il a été inscrit à l’agenda fédéral (à travers notamment l’Executive Order 12898 du président Clinton du 11 février 1994), d’autres défis ont dû être relevés. En particulier, ceux liés aux solutions à apporter.

Contention against the ways which have resulted in the increase of environmental problems in the most sensitive communities, first led community activists and researchers to resort to objective observations (Bullard, 1990; Cole and Foster, 2001). They created grids which link the environmental, social justice and racial segregation stakes: the latter not having been taken into account in the field of environmental issues up to then (Theys, 2007). Then, as the movement gained momentum and was put on the federal agenda, namely through President Clinton’s Executive Order 12898 of February 11, 1994, new challenges had to be met, essentially having to do with solutions to be found.

La recherche de compromis par le biais de l’octroi de contreparties ne date, en matière d’urbanisme et plus particulièrement d’implantation de grands équipements[1], ni d’aujourd’hui ni de l’émergence de la justice environnementale. Elle est au cœur même des pratiques, tant des maîtres d’ouvrage (entreprises publiques ou privées ou collectivité publique) que des gouvernements locaux et nationaux. Toutefois ces discussions sont souvent bilatérales, restreintes au pourvoyeur du permis et des autorisations et à la structure demandeuse. Elles ne traitent que des aspects directement en relation avec l’infrastructure et non des questions de qualité de vie.

Compromise through compensation is not new nor a consequence of the birth of EJ in the field of urban planning and especially for regional facilities of considerable scope.[1]It is of common practice among developers, whether they work for public, or private companies, or for the local public authorities or the state or federal governments. Agreement is frequently bilateral and generally limited to the party supplying the permit and the authorizations and the applicant party. The discussions deal with aspects directly related to the infrastructure and not at all the quality of life.

Par ailleurs des techniques telles que linkage zoning[2], inclusionary zoning[3], les development agreements[4] ont déjà tenté de lier les projets privés d’équipement avec la fourniture de services complémentaires. Ces dispositifs ne peuvent s’imposer aux grands projets qui exigent un processus de validation et d’acceptation impliquant l’Etat fédéré et l’Etat fédéral. De fait les villes n’ont pas compétence à imposer à un maître d’ouvrage public fédéral leurs décisions.

The application of techniques such as linkage zoning[2],inclusionary zoning, [3] and development agreements[4] have been tried out previously in order to link private projects for amenities with complementary services. This legislation cannot be applied to the greater projects which have to go through a process of validation by the Federated States and the Federal Government. In fact, cities have no right to impose their decisions to public Federal developers.

D’autres formes de régulation locale non prises en charge par les pouvoirs publics ont par conséquent été expérimentées, dont la négociation de community benefits agreement (CBA) (1).

That is why other types of local regulation, which are not dependent on local authorities, have been tried out and among these the community benefits agreement (CBA) (1).

Toutefois les militants de l’urbanité socio-environnementale sont confrontés à des systèmes politiques et administratifs parfois peu disposés à envisager cette redistribution et cette reconnaissance des individus et communautés. A Detroit, à l’occasion d’un projet de plateforme multimodale (Detroit Intermodal Freight Terminal - DIFT) et d’un autre de construction d’un nouveau pont rejoignant les villes de Windsor et Detroit (Detroit River International Crossing - DRIC), les associations d’aide sociale, de justice environnementale, de préservation de l’environnement ont décidé, du côté américain, d’unir leurs efforts pour obtenir du maître d’ouvrage public (Michigan Department of Transportation - MDOT) des mesures de compensation (2).

However, activists pushing for socio-environmental town-planning are confronted with political and administrative authorities who are sometimes unwilling to consider redistribution and the recognition of individuals or communities. For example, in Detroit, those involved in the plans for a multimodal platform (the Detroit Intermodal Freight Terminal – DIFT) and the construction of a new bridge linking Windsor and Detroit (Detroit River International Crossing -–DRIC), associations providing welfare, EJ, and environmental protection have decided to unite their efforts in order to obtain compensatory measures from the public developers (Michigan Department of Transportation) (2).

Il semble que l’expérimentation démocratique locale, qui passe par le registre informel puis contractuel, ne résolve pas les inégalités fondamentales contenues dans les dispositifs réglementaires et renforcées par des pratiques bien établies (3). C’est du moins ce que notre étude de terrain, qui a été menée en juillet 2008 et qui s’est appuyée sur l’exploitation d’articles de la presse locale et d’entretiens semi-directifs auprès des aménageurs, des associations et des représentants de l’administration fédérale et de l’Etat nous permet de conclure.

Experimenting in local democracy, proceeding from the informal level to a more formal contract, does not solve the fundamental disparities existing in regulations and that are enforced by well established practices (3). This is what the fieldwork we completed in July 2008 shows. We came to this conclusion thanks to our study based on articles published in the local press, and interviews with local planners, members of local grassroots associations, and State and Federal administration representatives.

1. Community benefits et justice environnementale aux Etats-Unis

1. Community benefits and Environmental Justice in the United States

1.1 Justice environnementale : redistribution et procédure aux Etats-Unis

1.1. Environmental Justice: reallocation and procedures in the United States

La législation fédérale et des états obligent les maîtres d’ouvrage dans leurs projets d’infrastructure aux Etats-Unis à prendre en compte la question de la justice environnementale d’abord d’un point de vue procédural et, dans une certaine mesure, d’un point de vue redistributif. En effet, les équipements polluants ou à risque ne doivent pas, a priori, être concentrés sur des zones socio-économiquement dégradées où vivent des populations vulnérables. Dans les études d’impact, un chapitre est consacré aux répercussions en termes de justice environnementale : la structuration socio-démographique du territoire (pourcentage des mères célibataires, de personnes concernées appartenant à des minorités ou ayant de faibles revenus, taux de chômage, etc.) est étudiée et prise en compte.

In the United States, Federal and State legislation make it mandatory for developers in charge of infrastructural projects, to take EJ into account: firstly at the procedural level and secondly and to a certain extent in the area of reallocation. Facilities that will or may entail pollution should not be densely concentrated in socially and economically run-down areas, where vulnerable people live. In the impact studies, a chapter is devoted to the repercussions on EJ in the area of the social and demographic territorial structure (the percentage of single mothers, the people affected belonging to minorities or with a low level of income, or affected by unemployment) which are analyzed and taken into account.

Toutefois, au-delà des mesures traditionnelles d’atténuation des impacts, il n’est pas prévu, notamment pour les projets de modernisation ou d’extension d’infrastructures, d’interventions particulières pour pallier une situation déjà présente d’injustice environnementale. D’où la revendication de certaines coalitions d’action – s’opposant au projet ou contestant le processus de décision – que les promoteurs, les maîtres d’ouvrage et les exploitants fassent preuve d’une implication sociale et écologique plus fortes.

However, beyond the traditional measures of assistance to help alleviate these negative elements, nothing has been planned for and particularly as far as modernization and the extension of the projects is concerned. No stopgap measures have been taken, in order to deal with existing environmental injustice. Thus one can understand the demands of some of the activist coalitions, opposed to the project, challenging the way decisions are taken. They want the property developers, the developers and those who run these facilities to be more involved socially and ecologically.

En fait la mise à l’agenda et l’institutionnalisation dans les années 1990 de la justice environnementale ont avant tout pris en compte la dimension procédurale des iniquités environnementales. Cela s’est traduit par l’implication de populations reconnues comme des communautés de justice environnementale dans des espaces de concertation dédiés.

In fact with EJ and its institutionalization at the top of the agenda, in the 1990s, we note that what came to the foreground was the procedural dimension of environmental injustice. This became obvious through forums of discussion, to which inhabitants belonging to acknowledged EJ communities, were committed.

Mais cela n’a répondu qu’aux questions de forme, et non aux problématiques de fond, dont celle du cumul sur un même territoire des inégalités sociales et environnementales. Si la législation et les réglementations existantes se rapportent davantage à la justice procédurale (intégration de nouveaux publics dans les processus de décision), d’autres modalités locales correspondent plutôt à une volonté redistributive et à une quête d’égalité substantielle[5]. Le recours à la compensation est une des modalités de ces expérimentations locales, souvent peu formelles et qui n’engagent pas les agences fédérales sur l’ensemble du territoire américain.

Yet this only corresponds to the form and not to the basic issues, such as the cumulating of social and environmental inequality in one single area. If the prevailing legislation and regulations pertain more to procedural justice (the integrating of new groups of people in decision making), other local modes deal mostly with the will to reallocate and to seek substantial equality[5]. Compensation is one of the modes in local experimenting, and often not a formal framework which federal agencies are committed to throughout the American territory.

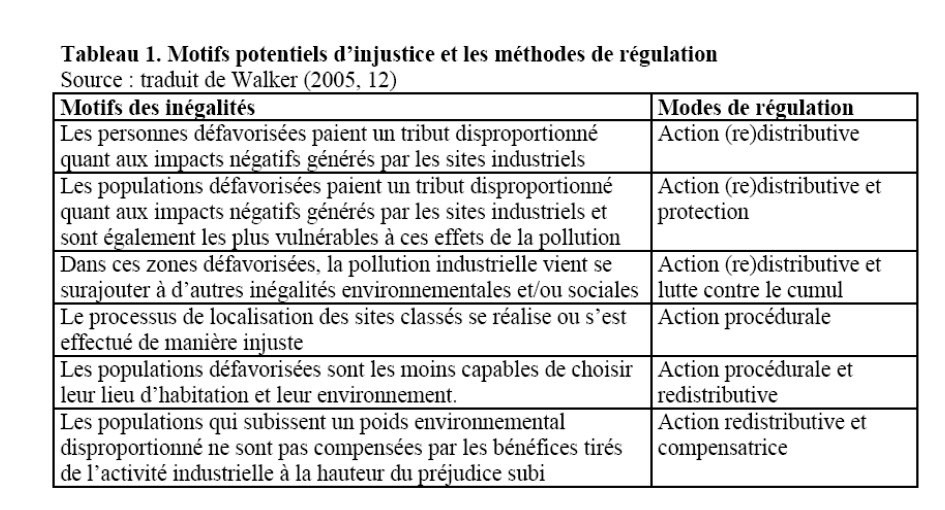

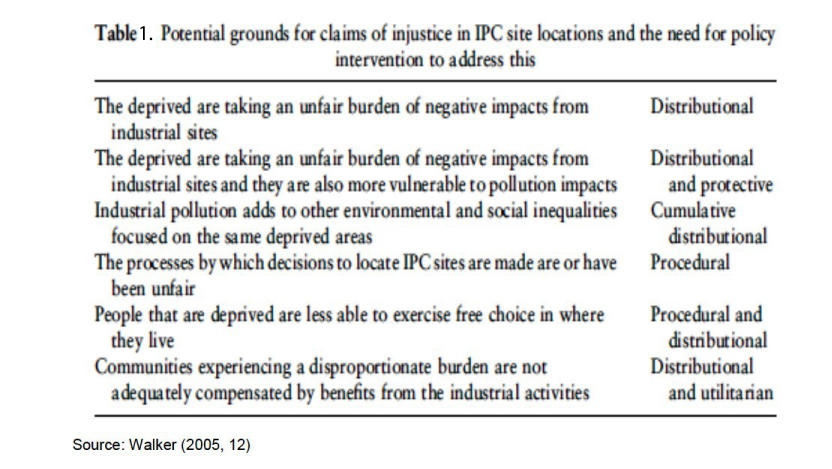

Le tableau suivant, même s’il est issu de la recherche universitaire britannique, démontre que la complexité des inégalités environnementales demande des interventions qui ne peuvent s’arrêter à une action procédurale.

The following table, resulting from the work done by British university researchers, shows how the complexity of environmental inequality makes outside intervention necessary and cannot be dealt with by a simple procedure.

Un même territoire peut se trouver à la croisée de plusieurs motifs d’inégalité ; il demande donc une (ré)action régulatrice de plusieurs ordres. Les community benefits agreements, ne résultent pas de l’application d’une législation spécifique, mais d’une co-construction locale. A ce titre ils tentent de donner une réponse plurielle et contextuelle. L’instrument compensatoire socio-environnemental reflète sous cette forme l’évolution des rapports de pouvoir entre acteurs sur un territoire. Le recours de plus en plus systématique à la contractualisation des relations territoriales permet d’éviter les bras de fer judiciaires.

One territorial area may cumulate many factors leading to inequality. Therefore that area will need several different types of regulatory elements in order to deal with the problems. The community benefits agreements (CBA) do not result from the application of specific legislation, but rather from local collaboration through a multifaceted system response to the question. In this respect the use of these agreements provides many possible and contextualized answers to the problems. The socio-environmental subsidy tool highlights the change in the power relationship between the different parties involved on the territory. Negotiating more and more systematically in the area of territorial problems has improved the situation and we can note fewer legal trials of strength these days.

Apparu en Californie, le recours au CBA ne concernait au départ que des maîtres d’ouvrage privés. Afin de faciliter l’acceptation de la modernisation de l’aéroport international de Los Angeles, la ville de Los Angeles qui en est gestionnaire en a consenti un. Peu à peu cette forme transactionnelle s’est diffusée, illustrant une forme renouvelée de l’action publique/privée (Lascoumes et al., 2005).

CBA was initially set up in California and at the outset involved private developers. In order to help facilitate the modernisation of the Los Angeles International Airport, the city (who manages the airport), accepted this type of solution. This type of transaction became popular and was adopted as an innovative public/private type of policy (Lascoumes et al, 2005).

1.2 Les community benefits agreements : un outil de compensation « multi-transactionnel » (Blanc, 1992)

1.2. The Community Benefits Agreement: a “multi-transactional” tool (Blanc, 1992)

Négociés depuis le début des années 2000, les CBA, héritiers des good neighbor agreements (accords de bon voisinage) participent de l’effort d’internalisation des coûts sociaux en contribuant à une meilleure équité dans la répartition des effets positifs et négatifs d’un équipement (Gobert, 2008).

Resulting from the negotiations that took place at the turn of this century (in the early 2000), the CBA is heir to the Good Neighbor Agreements and part of an effort to confine social costs in participating in better equity and the sharing of both bad and good effects of an impacting facility (Gobert, 2008).

Les CBA reposent sur quelques principes essentiels : inclusiveness (principe procédural : intégration de la société civile et négociation) et accountability (principe de résultat : responsabilité et mise en œuvre) (Gross, 2008). Inauguré dans la ville de Los Angeles, ce modèle d’empowerment, de négociation et de compensation (Baxamusa, 2008) a rapidement essaimé dans tout le pays. Il est présenté comme un processus gagnant-gagnant, car des bénéfices sont octroyés à la fois au pôle de la riveraineté[6] – associations, collectivités locales - (en matière d’emplois, de formation, de logement, d’espaces publics, d’environnement) et aux développeurs[7] (soutien politique, amélioration de l’image publique et possibilité d’éviter les recours judiciaires) (Gross et al., 2005 ; Annie Casey Foundation, 2008).

The structure of CBAs is based on some very essential principles. On one hand, inclusiveness which is a procedural principle having to do with Civil Society and negotiating procedures, on the other hand accountability which is based on the principle of obtaining results and implies responsibility and implementation (Gross, 2008). This empowerment model for negotiating and compensating was inaugurated in Los Angeles (Baxamusa, 2008), and quickly spread to the rest of the country. It is considered as a win-win process as the benefits are granted to the local resident groups[6] – the associations and the local public authority – for employment, professional training, housing, public parks and amenities and the environment, and to the developers who get political backing, improve their public image and will possibly avoid lawsuits (Gross et al, 2005; the Annie Casey Foundation, 2008).

La vision de l’environnement qui y est développée ne se limite pas à une appréhension strictement écologique et ne se restreint pas à la protection des milieux. Les solutions proposées sont par conséquent plurielles, jouant sur plusieurs registres de la vie urbaine : habitat, relations de travail (notamment salaires minimums, traitement égal des salariés syndiqués et de ceux qui ne le sont pas), transport (amélioration de la desserte pour les riverains), qualité de la vie (création de parcs, diminution des nuisances...). Toutefois elles sont fondées sur un principe de substituabilité limitée ; il n’est pas possible, en effet, de compenser une altération à un écosystème par une aide financière destinée à la réhabilitation d’un centre communautaire.

The development of an environmental concept in this approach is not restricted to its strictly ecological apprehension, nor limited to the protection of the environment. Therefore the proposed solutions are numerous and deal with many levels of urban life including the habitat, people’s working conditions (especially relative to minimum wages and the guarantee that the wages paid to union and non union staff members are identical), transportation (improvement of the local residents’ network) and finally the quality of life (such as the development of parks and the reduction of all types of pollution). The solutions are based on a principle of limited replacement. For example, it is impossible to compensate for the deterioration of an ecosystem by offering financial aid to be attributed to the restoration of a community center.

C’est à l’occasion de la demande d’autorisation du projet et souvent de l’étude d’impact environnementale (EIE) - qui recense les impacts écologiques mais également, dans une certaine mesure, les effets économiques et sociaux - qu’un tel accord peut être négocié. La démarche est souvent incrémentale ; développeurs, collectivités locales et pôle civique se situent dans une démarche de négociation constructive (integrative bargaining) qui passe préalablement par la formulation d’un diagnostic commun. Celui-ci prend la forme d’un Community impact report (étude des incidences communautaires) ou d’une Social impact study (étude d’impact social) dans les cas les plus formels.

Such an agreement may be negotiated for the request of the authorization of a project and for reports on the environmental impact assessment (EIA) listing the ecological consequences – and to a certain extent – the economic and social effects of the given project. The procedure is often an incremental one: the developers[7], the local public authorities, the civic groups all participate in constructive negotiations (integrative bargaining), which is initially formulated in a collective diagnosis. The framework is either a Community Impact Study or more formally a Social Impact Study.

Aux impacts et aux besoins diagnostiqués répondent des mesures spécifiques. Dans la négociation sont discutées non seulement les effets directs de l’infrastructure (déjà traités dans l’évaluation d’impact), mais aussi le cumul des difficultés subies par les populations. A ce titre on peut parler de négociations multi-transactionnelles, dans la mesure où la palette des sujets pouvant être abordés, pendant la période de négociations, est large. Ces transactions se font très souvent, dans le cas des CBA, dans une seule arène (dispositif ad hoc de réunions qui se succèdent ou dans le cadre de l’évaluation d’impacts du projet) ; il en résulte donc un document commun, et non une addition de protocoles découlant de différents processus.

Specific measures are adapted according to the needs or the various impacts found in the diagnosis. Not only are the direct effects of the infrastructure (previously analyzed in the EIA), but the total sum of difficulties the population underwent discussed. We can therefore call these multi-transactional negotiations, due to the variety of topics brought up. The CBA settlements usually take place in a single location (ad hoc discussions set up where meetings are held and the impact of the projects evaluated). To conclude, there will be a single document and not a collection of protocols resulting from the various processes.

Les CBA constituent des « accords supra-réglementaires ». Ceci pour au moins trois raisons. La première est qu’ils font rarement partie intégrante du document final de l’évaluation d’impact (Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) ou Record of decision (ROD)). D’ailleurs leur intégration dans le ROD présente quelques désavantages, car elle n’implique que l’agence gouvernementale, et non les membres du « pôle civique ». Ceux-ci ne peuvent donc pas recourir à la justice en cas de non respect des concessions. Il leur est également plus difficile de contrôler la mise en place effective des mesures (Larsen, 2009).

CBAs belong to the category of “supra regulatory agreements” for at least three reasons. First of all, they are rarely part of the final impact evaluation document called Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) or Record of Decision (ROD). Integrating the ROD entails several disadvantages, since only the members of the government agency are involved, but none of the members of the civics hub are deciders. They are thus unable to go to court in the case of failure to respect any concessions made. It is also more difficult for them to check the implementation of the measures taken (Larsen, 2009).

En second lieu, ces accords multilatéraux suppléent en quelque sorte aux lacunes de l’évaluation d’impact : prise en compte d’impacts « oubliés », des savoirs locaux, manque de participation... Ils interviennent souvent hors des arènes officielles de concertation (prévues soit dans l’EIE, soit par les gestionnaires de l’infrastructure).

Second of all, these multilateral agreements make up for the gaps that can be found in the impact evaluation and take the “neglected” impacts, the local know-how and lack of participation into account. They are frequently settled outside of the official consultation channels which are either provided for by the EIE or the authorities managing the infrastructure.

Pour finir, ces accords viennent en complément des législations existantes. Par exemple quand il n’existe pas, dans les juridictions où se négocient des CBA, de réglementation sur le salaire minimum (living wage provision) ou que certains corps de métiers ne sont pas couverts par lesdites réglementations, les coalitions en formalisent souvent la demande. C’est également une manière de combler la baisse des aides fédérales envers les villes et leurs programmes de réhabilitation, de logements : en effet l’initiative Strengthening America’s communities sous l’administration Bush s’est soldée par une baisse importante des aides pour le développement économique local, notamment le Community Development Block Grant (Le Roy, Purinton, 2005).

To conclude, we may note that these agreements are complementary elements to existing legislation. For example, when people with minimum wage (living wage provisions) or some professional categories are not covered by regulations in the courts of law in which the CBAs are negotiated, then the coalitions will often formally take action. It is also a way of compensating for the cuts in federal aid for housing rehabilitation programs. We can indeed point to the “Strengthening America’s Communities” initiative under the Bush administration, which ended in a considerable decrease in aid for local economic development and particularly in the case of the “Community Development Block Grant” (Le Roy, Purinton, 2005).

L’ensemble de ces éléments expliquent l’attrait de ces contrats sociaux locaux auprès de la société civile aux Etats-Unis, et plus particulièrement à Detroit, même si leur recours n’est pas encadré législativement et que peu retours jurisprudentiels permettent de lever les incertitudes juridiques (Salkin, 2008).

All of these points explain why local social contracts, which are negotiated with Civil Society throughout the United States, but especially in Detroit, appear to be so attractive, even if this course of action has no legal framework and few decisions taken in court coming to nothing lead to the lifting of legal uncertainty (Salkin, 2008).

2. Detroit, « the shrinking city » : un « enfer urbain » en voie de réhabilitation ?

2. Detroit, “the shrinking city”: an “urban hell” undergoing restoration?

« Pauvre, ségrégée, délabrée, Detroit a été, depuis la fin du programme des Empowerment Zones[8] en 2004, totalement abandonnée » (Popelard, 2009). L’aire métropolitaine de Detroit souffre d’une image très dégradée : elle est la ville de la déprise industrielle (Je Jo, 2002), de la relégation sociale et environnementale. Elle est souvent présentée comme un enfer urbain, “a cautionary tale for urban planners, for social workers, for the rest of us. Everything that is happening elsewhere because of the economy started here a long time ago. It’s like a Petri dish of all the things that have gone wrong.” (Carr, 2009) Elle semble en outre gangrénée par la corruption.

“Poor, run down, segregated Detroit ever since the end of the Empowerment Zones[8] program has been totally abandoned” (Popelard, 2009). Its image is debased and it is considered the city of industrial loss (Je Jo, 2002), of social and environmental relegation. It is often shown as an urban inferno, its downtown almost empty: “a cautionary tale for urban planners, for social workers, for the rest of us. Everything that is happening elsewhere because of the economy started here a long time ago. It’s like a Petri dish of all the things that have gone wrong” (Carr, 2009). In addition, corruption appears to be poisoning the city.

Elle fait partie des villes rétrécies (shrinking cities) qui suscitent depuis la fin des années 90 l’intérêt des chercheurs, non seulement pour comprendre les mécanismes de désertification urbaine, de baisse démographique, mais aussi pour élaborer des outils originaux afin d’y remédier. En ce qui concerne les Etats-Unis, le déclin urbain de la Rust Belt est dû à la fois à la désindustrialisation massive et à la suburbanisation. A Detroit, cette évolution est particulièrement évidente (Digaetano, 1999) : les difficultés économiques rencontrées par les trois grands constructeurs automobiles, l’abandon du centre-ville, se conjuguent à l’étalement de la ville et à un renforcement de la ségrégation sociale et raciale des banlieues. Fortement touchée par la désindustrialisation, l’automatisation des processus industriels, de nombreux emplois ont disparu dans les années 60 à Detroit et beaucoup de résidents ont quitté la ville, laissant des maisons et des magasins vides.

Detroit is among the “the shrinking cities” that have given rise ever since the end of the 1990s to researchers interest, not only helping to understand the mechanisms of urban depopulation and decreasing demography, but also to create new remedial tools. As far as the United States is concerned, urban attrition in the Rust Belt has been caused by massive de-industrialization on one hand, and suburban development on the other. This trend is particularly obvious in Detroit (Digaetano, 1999): as the economic hardships of the three major automobile manufacturers, the deserting of the downtown area in conjunction with the spreading of the city and the rise in social and racial suburban segregation show. Because it was greatly affected by de-industrialization and the automation of industry, many jobs disappeared in Detroit in the 1960s, and so a number of local residents left town, leaving their homes and stores empty.

A l’instar de Leipzig, Detroit est une « ville perforée » (Florentin, 2008) présentant quelques ilots d’activités et des banlieues plus ou moins bien intégréesau reste de la métropole. Ce déclin a de nombreuses conséquences en termes de diminution des capacités fiscales des villes concernées, de maintien ou non de services publics (réseau de distribution d’eau, d’électricité, desserte en transports) (Zepf, Scherrer, 2008)… Cependant le rétrécissement des villes (en Allemagne de l’Est, en Russie, aux Etats-Unis) n’est pas vécu comme insurmontable : il donne l’occasion aux collectivités publiques locales, aux autorités régionales de revoir leur conception de la ville, de la réaménager de manière plus durable, d’expérimenter de nouvelles formes de gouvernance et de nouveaux outils d’intervention (Florentin et al., 2009), faisant fi du paradigme de croissance.

Like Leipzig, Detroit is a “pierced city” (ville perforée (Florentin, 2008)) with pockets of economic activity and suburban areas that are more or less well integrated. The decline has led to the decrease in tax money and thus the selective cutting of public amenities (such as the water distribution, the electricity and urban transportation networks) (Zepf, Scherrer, 2008). Yet, the shrinking of cities in East Germany, in Russia and in the United States do not appear to be insurmountable and have led local public authorities and regional authorities to review their conception of town planning in a more sustainable way and to experiment with new ways of governance and new tools of intervention (Florentin et al, 2009), flouting the growth paradigm.

De même, il existe de multiples tentatives pour régénérer et transformer Detroit et lui donner une autre fonction que celle de carrefour routier, de centre de fret à laquelle les deux projets étudiés la cantonnent. Cette revendication a pris la forme de la négociation de CBA, les associations voulant appliquer le modèle d’origine californienne. Mais le transfert des bonnes pratiques se heurte à une configuration socio-politique locale différente, moins disposée à consentir un accord formel.

In the same way, there have been many attempts to revive and transform Detroit and to turn it into a place other than a road hub or a freight transportation hub which city planning had limited its function to. This demand led to a negotiating process via CBA, as member associations wanted the California model to be applied to Detroit. However, transferring good practices faces a different local social and political set-up, with members less willing to comply with formal agreement.

2.1 DRIC et DIFT : deux projets d’infrastructure sur une zone économiquement et socialement déprimée

2.1. DRIC and DIFT: two infrastructural projects set up in an economically and socially depressed area

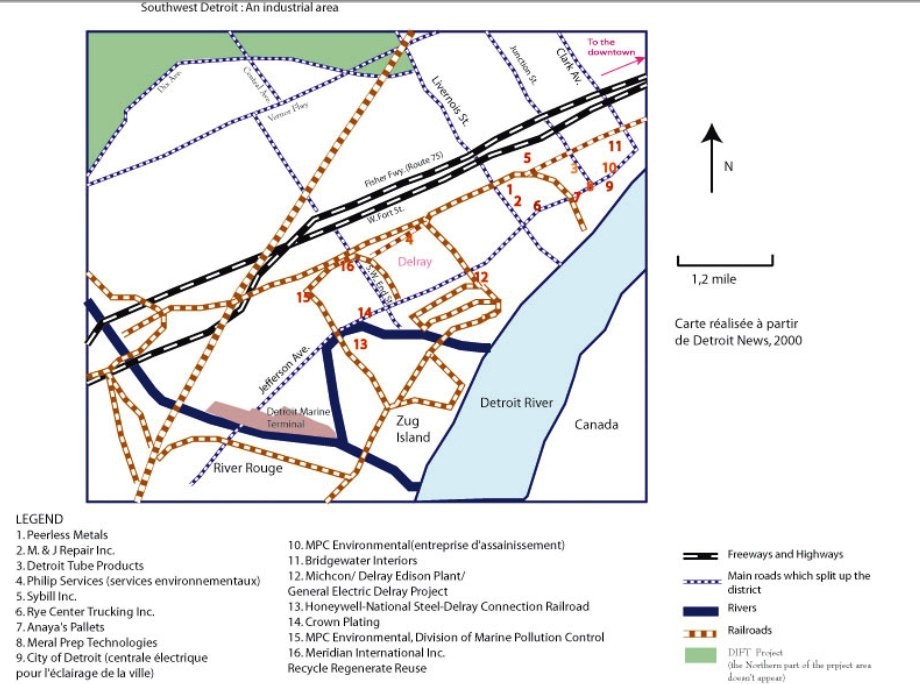

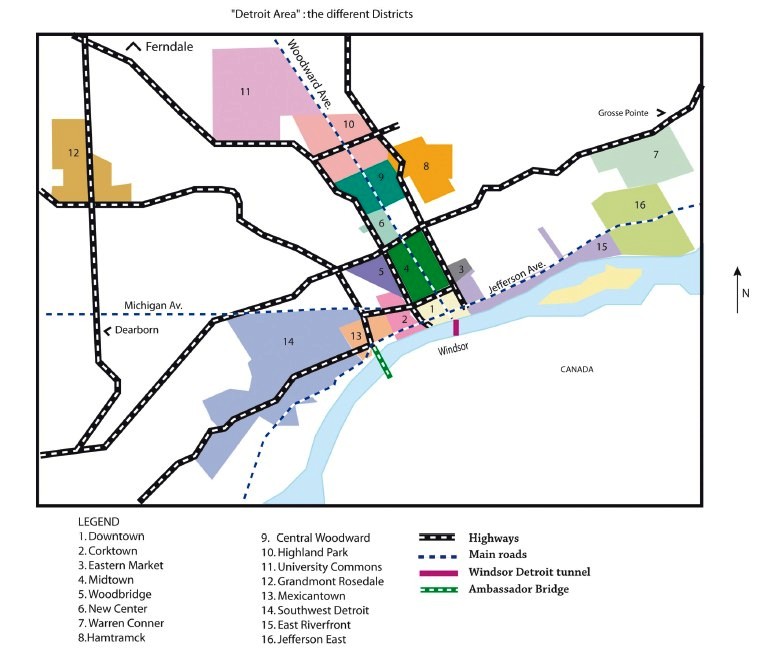

Southwest Detroit[9] (carte 1) dans lequel se situe Delray (voir les deux cartes ci-jointes) est un quartier de la ville de Detroit particulièrement défavorisé, présentant une grande diversité ethnique : des descendants d’immigrés hongrois, polonais, des Afro-Américains, des hispanophones installés de longue date (communauté mexicaine) ainsi qu’une importante communauté arabe. (Downey, 2005)

Southwest Detroit[9] (map n° 1) where Delray is located (see the two adjoining maps) is one of the most disadvantaged neighborhoods of the city, with great ethnic diversity and descendants of Hungarian, Polish, African-American and Spanish speaking Latin American origin (the latter are mostly of Mexican extraction and have been in the country for a very long time) and a large Arabic community as well (Downey, 2005).

Le paysage urbain compte de multiples friches urbaines et industrielles conférant une impression de vacance, de délaissement politique, qui conduit à des comportements illégaux (décharge illégale)[10]. “Housing property values in the area are extremely low: property values in the neighborhood average under $25,000 US (according to the U.S. 2000 Census) and in some cases are under $10,000. Housing demand is also low.” (University of Michigan, 2007).

The urban landscape comprises a number of urban and industrial wastelands, giving the impression that the area is vacant and, of political neglect. Because of this there is a trend towards illegal behavior which is exemplified by the use of illegal dumps[10]. “Housing property values in the area are extremely low: property values in the neighborhood average under $25, 000 US (according to the 2000 US census) and in some cases amount to even less than $10, 000. Housing demand is also low” (University of Michigan, 2007).

Il s’agit d’une des zones les plus fortement polluées de l’agglomération de Detroit ; elle concentre de nombreuses usines encore en activité et constitue un carrefour routier très emprunté qui fait la liaison avec le Canada (carte 2). Pour autant, dans cette partie de l’aire urbaine de Detroit, il existe une tradition de résistance face aux décisions prises par les autorités publiques.

The area is one of the most polluted in all of greater Detroit, in which a number of factories that are still running can be found, as well as a road network hub linking the area to Canada (map n°2). People here have traditionally expressed and resisted the decisions taken by public authorities.

L’usine de retraitement des eaux usées a été par exemple l’objet de contestations ; d’autres exploitants ont été poursuivis pour les nuisances et émissions malodorantes[11] de leur usine. Cet activisme n’est pas seulement le reflet d’une « juridiciarisation » des rapports de force aux Etats-Unis. Ce militantisme illustre plutôt la capacité de résilience de certaines communautés face à un environnement altéré.

They protested against the plant reprocessing waste-water. Factory directors were taken to court because of the pollution and the foul[11] emanations issuing forth from their plants. This type of activism does not only reflect how much legal procedures affect the balance of power in struggles such as these throughout the USA. This kind of activism illustrates how resilient some communities are in the face of the deteriorated environment they live in.

D’ailleurs les rapports industrie/promoteurs et pôle de la riveraineté ne passent pas toujours par la confrontation judiciaire.

However, the relationships existing between industry, property developers and the local residents do not always lead to court conflict.

Avant même la mise en discussion du DRIC et du DIFT, les communautés de Southwest Detroit s’étaient efforcées, dès les années 90, à plusieurs reprises, de sensibiliser les pouvoirs publics au besoin de rénovation urbaine :

As early as the 1990s and prior to launching a debate on DRIC and DIFT, the Southwest Detroit communities tried repeatedly to sensitize the public authorities to the need of renovating the urban structure:

“to get the railroads, to clean up the viaducts, stop clogging up the catch basins, etc., but no action has been taken. The movement towards intermodal traffic and the inevitable expansion of the freight transportation industry creates an opportunity for the immediate affected communities to leverage benefits from the State of Michigan.”

“…to get the railroads, to clean up the viaducts, stop clogging up the catch basins etc, but no action has been taken. The movement towards intermodal traffic and the inevitable expansion of the freight transportation industry creates an opportunity for the immediately affected communities to leverage benefits from the State of Michigan.”

Des accords avaient déjà été passés avec certaines entreprises octroyant des bénéfices aux communautés riveraines. Ainsi Synagro, qui traite les eaux usées dans une infrastructure située sur la Jefferson Avenue, a conclu en 2007 un Community Benefits Memorandum of Understanding (soutien financier à des projets locaux sur Delray, amélioration de l’information à destination des riverains, clauses sur l’accès à l’emploi, sur la réduction des émissions…) avec des organisations religieuses, environnementales et de voisinage.

Agreements had been reached between some of the companies, granting benefits to local communities. Thus Synagro, a company dealing with purifying waste water in an infrastructure located on Jefferson Avenue, settled for a Community Benefits Memorandum of Understanding in 2007 (they allocated funds for local projects in Delray, agreed to improve the circulation of information for the local inhabitants, created chapters dealing with enhancement of employment, and the reduction of emissions). They collaborated with local, religious and environmental groups.

C’est donc dans un contexte combinant opposition et recherche de dialogue entre aménageurs et société civile que les projets DIFT et le DRIC sont apparus. Ces deux projets de transport présentent plusieurs caractéristiques communes : ils sont proches géographiquement et ils impliquent à peu près le même réseau d’acteurs au niveau municipal, régional et national (voir cartes). D’ailleurs ils ont tous deux les mêmes maîtres d’ouvrage principal le MDOT, ainsi que la Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), les collectivités locales n’étant que des réceptacles qui soutiennent ou non les projets fédéraux et étatiques et qui ne bénéficient que d’une faible marge de manœuvre.

It is within this context of opposing views on one hand, and seeking a dialog between the planners and civil society on the other that the DIFT and DRIC projects appeared. Both of the transportation projects had several characteristics in common: they are located close by geographically and involve the same network of participants at the town, regional and national levels (refer to the maps). In fact they both have the same main developers: the MDOT and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). The town council organizations on the receiving end are only liable to support the federal or state level projects or reject them, and have very little leverage.

Dans leurs discours et les entretiens que nous avons effectués, les promoteurs ont toujours souhaité séparer les deux projets malgré les liens soulignés par la société civile (voir figure 1). Toutefois peu à peu des discussions ont été amorcées pour corréler les deux, au moins pour prendre en compte les impacts cumulés, en termes de pollution atmosphérique et de congestion routière.

In their speeches and in the interviews we gave, the promoters always wanted to make a distinction between the two projects, contrary to Civil Society, which underlined the strong links between them (see illustration n° 1). However, after some time, discussions made a link between both projects and took the impact of air pollution and traffic congestion into account.

Le MDOT, s’est cependant refusé à signer un CBA ; il préfère intégrer dans le ROD les différentes mesures d’atténuation et en discuter au cours de l’élaboration de l’étude d’impact.

Yet the MDOT refused to sign a CBA, preferring to integrate various mitigation measures in the ROD and discuss the matter when elaborating an impact paper.

"The FHWA and MDOT will partner with the City of Detroit and other federal, state and local agencies and cities to develop concepts by which enhancements can be made to Delray as it becomes the “Host Community” for the DRIC project.” (Project Mitigation Summary Green Sheet in FEIS 2008)

“The FHWA and MDOT will partner with the City of Detroit and other federal, state and local agencies and cities to develop concepts by which enhancements can be made to Delray as it becomes the “Host Community for the DRIC project” (Project Mitigation Summary Green Sheet in FEIS 2008).

Il considère que les arènes formelles qu’il a mises en place satisfont aux exigences de participation des populations concernées. Ainsi ont été organisés des comités techniques d’une part et des réunions avec la population d’autre part, notamment pour choisir le lieu d’ancrage du pont. Des ateliers ont eu pour objectif non seulement de réfléchir à la forme et à l’esthétiquedu futur pont entre le Canada et les Etats-Unis, mais surtout à l’aménagement de la place où convergeront les voies routières et où un centre douanier sera construit.

They consider the formal places where debates are held, good enough to satisfy the demands of the affected population. Thus technical committees on one hand, and assemblies organized with the local residents on the other, were arranged to decide on the location for the anchoring of the new bridge. Workshops were not only set up aiming at taking the design for the future connection between Canada and the United States into consideration, but their participants moreover decided where the road network should converge and where a customs center was to be built.

De même, des Local advisory committees (comités de suivi locaux) comprenant des élus, des représentants d’association ou de groupes d’intérêt se tiennent mensuellement. Y sont discutés la concrétisation des demandes de la coalition, l’avancée des travaux, les points litigieux. Des réunions communes ont également lieu avec le Local Agency Group (comités de pilotage) qui rassemble, lui, les acteurs institutionnels (ville de Detroit, les écoles publiques, la Michigan State Housing Development Authority, la ville de Dearborn, etc.).

In the same way, the Local advisory committees including town councillors, members of associations or of interest groups gather once a month. Their agenda deals with the implementation of the coalition’s demands, the state of works-in-progress and questions of litigation. Other assemblies are held in conjunction with the Local Agency Group (the steering committee) comprising institutional members (from the City of Detroit, the local public schools, the Michigan State Housing Development Authority and the City of Dearborn, etc).

Mais étant donné que le MDOT est compétent avant tout sur les questions de transport, il agit donc davantage comme intercesseur mettant en réseau les acteurs que comme ‘actant’. Comment expliquer cette relative retenue de maître d’ouvrage et son non engagement dans l’implémentation d’une forme de CBA ? Faut-il y voir seulement un échec de la société civile à devenir « incontournable » dans le processus de décision?

But, as the MDOT essentially has the authority to deal with transportation issues, their members act as intercessors helping those involved to become fully-fledged committed actors. How can one explain the relative restraint on behalf of developers and their refusal to become committed in implementing some form of CBA? Can this only be considered as the failure for Civil Society to be part of the decisional process?

2.2 La structuration du pôle civique. Aléa et échec provisoire de la coalition contre le DIFT

2.2. Structuring of the civics area. Uncertainties and temporary failure of the coalition opposed to DIFT

Le DIFT[12] a été justifié selon le MDOT et la FWHA par le besoin de satisfaire l’accroissement du trafic et donc d’agrandir les capacités de transbordement des marchandises de la route vers le rail. L’agglomération de Detroit comprend déjà quatre terminaux intermodaux. Il s’agissait pour les agences gouvernementales de définir une stratégie locale équilibrée en concentrant les flux et en accélérant le traitement des marchandises.

According to MDOT and FWHA, DIFT[12] was vindicated by the need to deal with the increase in traffic and to expand transhipment capacity from road to rail. Greater Detroit already has four intermodal terminals. The aim for the government agencies is to define a local strategy in order to provide a well regulated flow of goods and to speed up the processing of the goods.

Pourtant selon certaines recherches, les bénéfices économiques ne sont pas immédiatement évidents pour la zone. “Freight prosperity in Detroit is dependent on the prosperity of industrial production. Most freight facilities do not attract high-value production facilities; rather they tend to attract lower-value freight service, such as truck parking lots and container yards.” (Bailey, 2001, 4)

However, according to some elements of research, the expected economic benefits will not be immediately noticed in the area. “Freight prosperity in Detroit is dependent on the prosperity of industrial production. Most freight facilities do not attract high-value production facilities; rather they tend to attract lower-value freight service, such as truck parking lots and container yards” (Bailey, 2001, 4).

En outre, Southwest Detroit et le sud est de Dearborn[13]sont des localités très bruyantes : les camions ne cessent de passer, des flots de poussière envahissent les rues, les trottoirs sont quasiment inexistants ou malaisés à emprunter, les routes peu entretenues sont défoncées. Le projet pourrait, si des mesures d’accompagnement sont acceptées, être une opportunité pour revaloriser le quartier et ses alentours. Mais de fait, celui-ci subit déjà de nombreuses nuisances qui ne sont peu ou pas atténuées par des mesures de mitigation ou de compensation. La modernisation et l’extension d’un centre de fret vont augmenter ces inconvénients, la pollution atmosphérique, le passage des poids-lourds.

In addition, Southwest Detroit and Southeast Dearborn[13] are very noisy areas: trucks keep passing through, dust covers the streets, the sidewalks are practically inexistent or not easy to walk along. Maintenance of the streets is almost inexistent and the streets are full of potholes. If the accompanying measures were accepted, the project could provide the opportunity to upgrade the neighborhood and its surroundings. In fact, the area already suffers from many sources of pollution which are hardly lessened by mitigation or compensation measures. The modernization and expansion of a freight hub will increase the inconveniences, the air pollution and heavy truck thoroughfare.

Le projet DIFT a donc suscité moult oppositions. En juillet 2002 le conseil municipal de Detroit a adopté une motion considérant le projet comme non nécessaire. Des résolutions en 2003 et 2005 sont venues confirmer ce point de vue : « the Detroit city Council opposes the continued decimation and destruction of the communities of southwest Detroit through the speculative effects of various public and private issues » (intégrant également la condamnation du DRIC) et ont critiqué l’absence de réelle étude d’impact sur les conséquences sanitaires.

That is why DIFT resulted in so much opposition. In July 2002, the Detroit town council passed a vote considering the project unnecessary. The resolutions of 2003 and 2005 substantiated this point of view: “The Detroit City Council opposes the continued decimation and destruction of the communities of southwest Detroit through the speculative effects of various public and private issues”. They also condemned DRIC and criticized the lack of a reliable study on the impact and subsequent sanitary consequences.

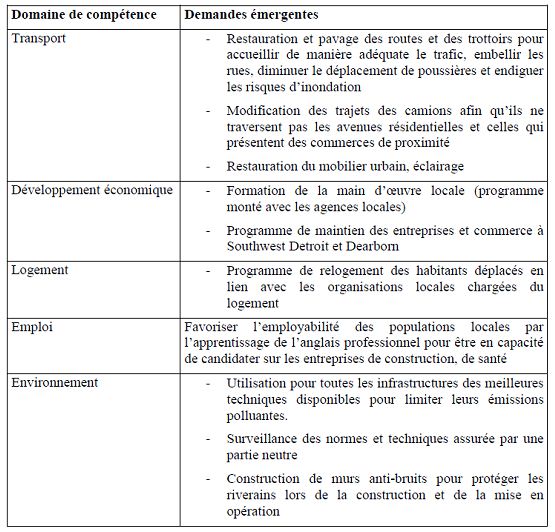

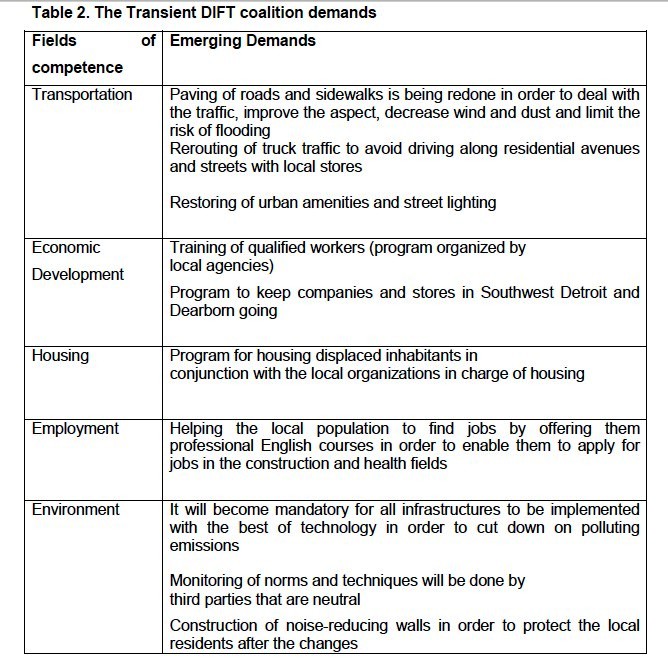

Par ailleurs plusieurs groupes représentant les différentes communautés de riverains ont fondé une coalition (Communities for a better rail alternative) : Southwest Detroit Environmental Vision (une association qui encourage le développement durable), ACCESS (Arab Community Center for Economic & Social Services), Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, Sierra Club – Detroit, Southwest Detroit Business Association, des représentants de l’Etat du Michigan, Ecology center… Ils ont formalisé des demandes dans un mémorandum listant les priorités environnementales (tableau 2).

Moreover, several other groups representing other communities of local residents created a coalition (Communities for a better rail alternative): Southwest Detroit Environmental Vision (an association promoting sustainable development), ACCESS (Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services), Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, Sierra Club-Detroit, Southwest Detroit Business Association, Michigan State representatives, Ecology Center. They formalised their demands in a memorandum listing their environmental priorities (Table 2).

Cependant la coalition a éclaté entre, d’une part, ceux qui soutenaient le projet mais souhaitaient que leurs propositions soient intégrées par le MDOT et, d’autre part, ACCESS et la ville de Dearborn, qui privilégiaient le statu quo (c’est-à-dire la non réalisation du projet). La tension ne s’est pas créée entre les « anti-développement » et les « pro-développement », ainsi que les maîtres d’ouvrage caricaturent parfois la situation. Ce sont deux appréhensions des rapports de pouvoir qui se sont opposées.

However, the coalition split into two groups. On one hand, there were those who favored the project but wished their proposals to be integrated into MDOT, and on the other, ACCESS and the city of Dearborn supported the status quo and wished for the non application of the project. We cannot claim that tension arose between the “anti-development” and the “pro-development” parties as developers tend to simplify the situation. In fact, we see in this situation two distinct apprehensions and opposing power relationships.

Malgré ces dissensions, un certain nombre de mesures d’atténuation et de valorisation de l’environnement ont été intégrées dans le FEIS. En liaison avec la ville de Detroit, le MDOT a prévu un réaménagement du système routier environnant, une diminution du trafic de camions sur les rues résidentielles, des murs anti-bruit dans certaines zones, et surtout une reconfiguration esthétique (pavage des rues, éclairage, mise à disposition de trottoirs).

In spite of existing disagreements, some mitigating and environmental improvement measures were adopted by FEIS. MDOT has programmed the reorganizing of the local road network, less truck traffic on residential streets, the building of noise reducing walls in certain areas and above all the beautifying of the area (road reparation, building of new sidewalks, street lighting improvement).

En coopération avec la Michigan Economic Development Corporation, la Detroit Economic Growth Corporation, et le Dearborn Department of Economic Development, une étude sur les opportunités de développement économique (commerces et services de proximités) de la zone doit être menée.

A study of economic development opportunities relative to local businesses and public services in the area resulting from collaboration between the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation and the Dearborn Department of Economic Development have yet to be written.

Le MDOT s’est engagé à participer au financement des efforts du SEMCOG (Southern Michigan Council of governments) pour établir un plan d’action contre les particules fines. Le MDOT remplacera par exemple ses équipements de manutention des conteneurs par des appareils, fonctionnant non plus au diesel seul, mais électriques ou hybrides.

MDOT has promised its commitment in financing SEMCOG’s efforts (Southern Michigan’s Council of Governments) to start a campaign to deal with small particles. For example, MDOT has decided to replace devices for container handling currently run by diesel energy which would be run by electrical or hybrid devices instead.

Nous remarquons cependant que ces avancées restent dans le cadre de ce qui se fait usuellement en termes de mitigation.

However, these advances remain within the limits of those ordinarily found in the mitigation process.

2.3 Les avancées timides et incrémentales de la DRIC Community Benefits Coalition

2.3. The DRIC Community Benefits Coalition’s tentative and incremental advances

Le DRIC, projet binational, permettrait quant à lui de pallier le manque de passages routiers pour traverser la rivière Detroit. Selon une étude sur l’impact économique de la frontière Detroit/Windsor, le corridor Montreal-Toronto-Windsor-Detroit-Chicago est l’une des voies de transports les plus denses et les plus interconnectées en Amérique du Nord. Les capacités actuelles, celles couplées du tunnel et de l’Ambassador Bridge[14] (géré par un opérateur privé, réunissant la Detroit International Bridge Company (DIBC) et la Canadian Transit Company), sont limitées et ne peuvent répondre à l’accroissement des échanges.

The DRIC binational project would compensate for the lack of roads crossing over the Detroit River. According to a report related to the economic impact at the Detroit-Windsor border, the Montreal-Toronto-Windsor-Detroit-Chicago corridor is one of the densest transportation throughways and places of interconnection in all of North America. The current capacity of the combined tunnel and the Ambassador Bridge[14] run by a private operator and linking the Detroit International Bridge Company (DIBC) and the Canadian Transit Company has reached the limit and the infrastructure would be unable to undergo a further increase in traffic.

Une coalition d’associations et de représentants politiques a vu le jour. La DRIC Community Benefits Coalition (CBC)[15], réunit sensiblement les mêmes acteurs que pour le DIFT, dont le Delray community Council (DCC), mais se veut plus intégrée et plus réactive. Elle a décidé de soutenir le projet sous certaines conditions :

A coalition of associations and political representatives has come into being. The DRIC Community Benefits Coalition (CBC)[15] comprises approximately the same members as the DIFT Coalition and namely the Delray Community Council (DCC) but claims to be better integrated and more resourceful. They decided to support the project under certain circumstances:

“While a new border crossing will have serious detrimental effect on a fragile community, it can also act as a catalyst for redevelopment”.

“While a new border crossing will have a serious detrimental effect on a fragile community, it can also act as a catalyst for redevelopment.”

“We also believe the best way for this to occur is the formulation of a legally binding community benefits agreement between the residents, local organizations, the State of Michigan, and the Federal Highway Administration. Such an agreement would legally guarantee that the explicit and implicit promises made to the host neighborhoods would be fulfilled. This would also insure that there would be economic reciprocity between the international border crossing entity and businesses, non-profit agencies, and community members in the impact area.” (Community Benefits Coalition, 28 avril 2008, Commentaire du DEIS DRIC)

« We also believe the best way for this to occur is the formation of a legal binding community benefits agreement between the residents, local organizations, the State of Michigan, and the Federal Highway Administration. Such an agreement would legally guarantee that the explicit and implicit promises made to the host neighborhoods would be fulfilled. This would also ensure that there would be economic reciprocity between the international border crossing entity and business, non-profit agencies, and community members in the impact area.” (Community Benefits Coalition, April 28th, 2008, DEIS DRIC commentary)

De fait, parmi les nombreux impacts, le DCC (2009) décompte le déménagement forcé de 257 ménages, l’exposition de populations vulnérables au bruit, un accès plus difficile à certains espaces, la perte de lieux culturels significatifs (dont l’église Saint Paul African Methodist Episcopal)… La critique la plus sévère se situe dans l’appréhension déficiente par le FEIS, dans le FEISFEIS des impacts directs et cumulés sur la santé et l’environnement, de même qu’une mauvaise estimation des retombées sur le commerce local de la suppression de certains itinéraires piétons.

In fact, among the numerous impacts the DCC reported in 2009, they counted 257 families who were moved out of their homes, they found many neighborhoods where people were subjected to high levels of noise and had difficulty in accessing parks or playgrounds, or lost of some their important cultural centers (among them the Saint Paul African Methodist Episcopal church). But the greatest criticism of all was that FEIS was unable to grasp direct and repeated impacts of the project on health conditions, the environment, on local businesses or the removal of some sidewalks for people to get around town.

La commission d’urbanisme de la ville de Detroit, bien que consciente des limites de sa prise de position, a soutenu cette démarche visant à demander des community benefits (bénéfices pour la population). Ceux-ci concernent le cadre de vie (la réduction du bruit, des vibrations, de la pollution lumineuse créée par l’infrastructure une fois opérationnelle) et reflètent l’attachement à une identité locale.

The urban planning commission for the city of Detroit, aware of its own limited position, was in favor of applying for “community benefits”. It all had to do with the environment (noise abatement, vibration, light pollution which the opening of the set-up would entail) and reflects commitment to local identity.

L’un des impacts majeurs sur le tissu social préexistant est le déménagement et le relogement de familles, procédures qui s’avèrent souvent traumatisantes et qui déstructurent les réseaux de sociabilité. La coalition a défendu le principe de “village concept” pour garantir un respect des liens entre les individus et a demandé que les fonds du programme fédéral de stabilisation des voisinages soient affectés à cet objectif.

One of the major impacts on the existing social fabric was the moving out and relocation of families, often a traumatic affair, leading to the deconstruction of social networking. The coalition was favorable to the “village concept” principle in order to ensure links between individuals living there. They requested federal program subsidies for the stabilisation of neighborhoods to be funnelled towards this objective.

Il s’agit également de préserver le patrimoine historique (tels Fort Wayne, de nombreuses églises datant du début du 19e siècle) .Certains objets ou lieux du territoire cristallisent ainsi l’attention en ce qu’ils fondent l’identité d’un territoire, qu’ils sont emblématiques de la relation asymétrique entre le promoteur et le « pôle civique ». C’est le cas du lycée car c’est une manière de dénoncer que les plus vulnérables sont les plus touchés et qu’il faut donc agir.

It is important to preserve historical landmarks such as Fort Wayne and a number of churches built in the early 19th century. Some of the buildings and places, which exemplify territorial identity, are symbolic of asymmetric relationships existing between the property developers and public civic centers. A case in point has to do with the local High School showing that the most vulnerable people are the most affected and so as protesters claim it is essential to react.

“All of the alternative locations for the potential DRIC project will be immediately adjacent to Southwestern High School and thus will significantly impact the current and future student populations. (…) At minimum, traffic routing, noise barriers, and vegetative buffering will be necessary to minimally reduce impacts. Any of the alternatives that provide more distance from traffic on the plaza would be preferred, as these may make differences in the local air quality. (commentaire 29 avril 2008, DEIS DRIC)”

“All of the alternative locations for the potential DRIC project will be immediately adjacent to Southwestern High School and thus will significantly impact the current and future student populations. (…) At minimum traffic routing, noise barriers, and vegetative buffering will be necessary to minimally reduce impacts. Any of the alternatives that provide more distance from traffic on the plaza would be preferred, as these may make differences in the local air quality” (Comments made on April 29th 2008, DEIS, DRIC).”

Les aspects de redistribution économique ont également été développés (création d’emplois et de formations ciblées, identification des besoins de la population en termes de services), au même titre que la vigilance à l’égard de l’environnement (demande de financement d’études sur la dispersion des émissions atmosphériques, de prise en compte de la pollution des eaux).

Different aspects of economic reallocation have also been developed (job creation, targeted professional training, identification of the local population’s needs in terms of services) as well as a close watch on the environment (requesting of financing for studies in the area of air pollution and water pollution).

Nonobstant des concessions du MDOT apparemment plus importantes que pour le DIFT, l’aménageur principal reste en retrait. Certains fonds des projets sont dédiés au relogement, mais les parties prenantes locales tentent de trouver des sources de financement complémentaires. Ainsi un des membres de la DRIC CBC, travaille avec la Michigan State Housing Development Authority et d’autres associations à cette tâche.

Despite MDOT’s concessions, which were apparently greater than for DIFT, the main city planner has not been very committed. Part of the funding for the projects have been allocated to new housing for those evicted but the local parties concerned are trying to get additional financial support. Thus one of the DRIC CBC members is collaborating with the Michigan State Housing Development Authority and some other associations in order to accomplish the given task (Bridging Communities, Southwest Solutions/Bagley Housing, and People’s Community Service).

Pour l’emploi, le MDOT joue plutôt le coordonnateur entre la ville de Detroit, le Michigan Departement of Labor and Economic et l’association Bridging Communities (insertion des habitants de Delray dans la construction). D’autres « compensations » sont en cours de négociation, puisque le processus d’évaluation environnementale n’est pas encore achevé.

As far as employment is concerned, the MDOT is playing the role of coordinator between the City of Detroit, the Michigan Department of Labor and Economics and the Bridging Communities Association (for the integration of the inhabitants from Delray in the construction professions). Other compensatory measures are currently being negotiated, as the environmental evaluation process is not yet completed.

En ce sens, la démarche n’est pas un modèle de démocratie délibérative, de co-construction de la décision comme de précédents CBA semblaient l’avoir inauguré. L’agence MDOT a la mainmise du projet et ne veut pas être amenée à concéder plus qu’elle ne le souhaite en termes de contreparties. La concrétisation de la justice environnementale reste donc limitée. Celle-ci dépend certes des compétences qu’aura su développer la société civile, mais aussi de sa capacité à déplacer le débat vers l’accès à un véritable droit à la ville et à promouvoir cette vision vers d’autres entrepreneurs politiques.

The process in this respect is not a democratic deliberative model, with the collaboration of both parties aiming at reaching decisions, as the CBAs had previously initiated. The MDOT agency runs the project and does not want to give more concessions than initially decided as compensation. Therefore, the implementation of EJ is restricted. Everything hinges on the competences the Civil Society has promoted, but also its capacity to move the debate into the arena of true entitlement to the Right to the City and promotes this view for other political actors.

3. L’émergence d’un « droit à ville » respectueux de l’environnement ?

3. The birth of a true “Right to the City” respectful of the environment?

Depuis l’émergence du mouvement de justice environnementale et son institutionnalisation aux Etats-Unis , beaucoup d’universitaires ont investi ce domaine. Beaucoup de critiques ont fusé, notamment parce que certaines recherches péchaient en termes de méthodologie, de prise en compte des échelles et adoptaient un ton volontairement accusatoire. Le cas de Detroit montre que nulle étude ne peut s’abstraire du contexte territorial et historique. Constater une situation d’iniquité à un moment donné ne permet pas de tisser des liens de causalité immédiatement ; plusieurs facteurs explicatifs peuvent se cumuler : le fonctionnement des marchés fonciers et locatifs sur le long terme[16], les politiques d’occupation des sols qui concentrent les industries à un endroit et où se sont installés les employés, le choix délibéré d’un développeur de s’implanter là où il pense que la contestation sera moindre, car peu organisée et bénéficiant de peu de moyens. David Pellow (2004) propose d’ailleurs un cadre d’analyse pour dépasser l’univocité de certaines démonstrations. A son sens, trois dimensions doivent être intégrées : l’histoire (pour dépasser l’évènement ou le résultat nuisible et contesté), l’ensemble des décisions qui ont produit cette inégalité environnementale (ce qui demande de prendre en compte les multiples acteurs y contribuant directement ou indirectement), le cycle de vie (contexte territorial mais aussi social qui permet de comprendre pourquoi, à un moment donné, la distribution des coûts et des bénéfices est considérée comme injuste). Les inégalités environnementales répondent plus fréquemment à des raisons systémiques que strictement contextuelles. Or il semble que sur les deux projets, l’aménageur comme les représentants de la société civile n’aient pu s’entendre sur un diagnostic et des objectifs clairs.

Ever since the EJ movement began and was institutionalized in the United States, a number of university scholars have done research on the subject. Lots of criticism came from all sides especially as some of the research was lacking in methodology, had not taken scales into account and willingly chose to take an accusatory position. The case of Detroit shows that no study may cut itself off from territorial and historical contexts. An iniquitous situation, noted at a specific point, does not allow people to identify causal links immediately. Several explanatory factors can be combined: the real estate market and long term property rentals[16], zoning regulations policies for industrial concentration in areas where the employees have settled, the deliberate choice for developers to build in places where they believe there will be less protesting as people there are not well organized and lack the means to do so. David Pellow (2004) has proposed a framework for analysis to go beyond the univocal dimension of some of the points demonstrated. According to him, it is important to integrate three dimensions to the analysis: the historic aspect (in order to expand the scope beyond the present event itself or its disputed and negative results), to take all the decisions having created environmental inequality (therefore implying that the many actors involved directly or indirectly are taken into account), to look at the life cycle (the territorial and social context helping to understand why at one point costs and benefits are seen to be unfair). Environmental inequality is often the consequence of systemic reasons rather than contextual reasons, strictly speaking. It seems that for both projects the city planners as well as the Civil Society representatives were unable to reach an agreement concerning the diagnosis and set clear objectives.

3.1 L’insuffisance des compensations socio-environnementales pour répondre aux maux urbains

3.1. Lack of social and environmental compensation for the urban damage wrought

Le pôle civique qui, à Detroit, a tenté d’infléchir les deux projets portés par le MDOT, se situe dans une perspective de régénération urbaine, de réhabilitation des quartiers (Bezdek, 2006). Il considère que si des mesures d’accompagnement adéquates ne sont pas réfléchies et implémentées concomitamment à la réalisation de l’équipement, celui-ci, aussi utile soit-il aux échelles régionale et nationale, n’aura aucun impact positif sur son milieu d’accueil et aggravera la situation sociale et environnementale d’un territoire dégradé.

The civic pole tried to modify the objectives settled by the MDOT. Their policy is part of the framework for urban revival and the restoration of neighborhoods (Bezdek, 2006). They consider that if adequate accompanying measures are not well thought through and implemented concomitantly to the achievement of the program, then no matter how useful for the region or nationwide the program is, it will have no positive impact on the receiving end and will worsen the social and environmental condition of an already rundown area.

“Few or no residents are employed by local businesses, which is a break with the historical pattern of the neighborhood. (…) In 2000, of 1168 workers 16 and older in the three census tracts that comprise Delray, zero traveled less than 5 minutes to work, and only 121 (10.4%) traveled between 5 and 9 minutes (U.S. Census 2000). In short, the Delray neighborhood and the local economic infrastructure are not highly integrated, as they once were. Rather, that infrastructure is oriented toward the regional and national economy, especially the transportation network, and is effectively not placespecific.” (Michigan University, 2007)

“Few or no residents are employed by local businesses, which is a break with the historical pattern of the neighborhood ((…) In 2000,of 1168 workers 16 and older in the three census tracks that comprise Delray, zero travelled less than 5 minutes to work, and only 121 (10.4%) travelled between 5 and 9 minutes US census 2000). In short, the Delray neighborhood and the local economic infrastructure are not highly integrated, as they once were. Rather, that infrastructure is oriented toward the regional and national economy, especially the transportation network, and is effectively no place specific” (Michigan University, 2007)

Ainsi les membres de la DRIC CBC ont également demandé à la ville de Detroit que le plan d’occupation des sols de Delray soit intégré au City Master Plan de Detroit afin de travailler à une échelle pertinente sur la revitalisation de la ville. Il s’agirait notamment de trouver des instruments pour l’acquisition et la mise en valeur des commerces et bâtiments vacants, de détruire ceux qui sont dangereux et ne peuvent faire l’objet d’une réhabilitation et de revoir l’utilisation du réseau viaire par les poids lourds.

Thus the members of the DRIC CBC have also requested that the City of Detroit integrate zoning regulations for Delray be integrated in the Detroit City Master Plan, in order to work on a relevant scale to revitalise the city. It would especially be useful to find the appropriate tools in order to purchase and develop businesses and empty buildings and to destroy those that are considered dangerous and not liable to be restored and finally to see how heavy goods trucks could use the road network.

La discussion autour de community benefits se veut créatrice de valeurs, en essayant de concilier les aspects sociaux et environnementaux. Elle cherche à dépasser les fonctions assignées à l’infrastructure (amélioration de l’accessibilité en transport, par exemple) pour mettre en avant une vision territorialisée des enjeux.

The debate regarding community benefits aims at being beneficial, through the reconciliation of social and environmental aspects. It is not simply limited to its infrastructural function (improvement of the local transportation network, for example) but should target a territorial view of what is at stake.

Mais il manque une échelle métropolitaine à laquelle ils pourraient être réfléchis entre acteurs privés et acteurs publics et devenir des politiques urbaines, dont l’objectif serait d’atténuer les disparités de richesse. Celle-là, malgré le SEMCOG[17] et les initiatives réussies de certaines organisations[18], reste peu envisageable en raison des inégalités de richesse entre centre ville et banlieues (Madden, 2003) et des différences politiques et ethniques.

However, what is lacking is a metropolitan scale where the community benefits could be discussed between the private and public forces and become part of an urban policy to alleviate disparities in wealth. This in spite of the successful initiative of SEMCOG[17] and some of the metropolitan organizations[18]does not seem to be conceivable, due to the disparities of wealth between downtown and the suburbs (Madden, 2003) and the different politics and ethnic make-ups in those areas.

La très grande fragmentation de la gouvernance locale et régionale, l’autonomie des pouvoirs locaux (urbains et suburbains) ainsi que les faibles marges manœuvres des gouvernements locaux très endettés, sont un frein à la régionalisation de problématiques qui, traitées à un niveau supérieur, seraient sans doute l’objet de politiques publiques plus efficaces et plus efficientes, car mieux coordonnées, ne sédimentant plus une situation d’inégalités (Jacobs, 2003).

The division in local and regional governance, the autonomy of local urban and suburban politics, and insufficient leeway for the deeply indebted local government: all add to the slowing down of regional planning. Were these questions to be dealt with at a higher level, then no doubt the public policies would be more effective and efficient as they would be better coordinated and would not entail disparity (Jacobs, 2003).

“Metropolitan areas in the Midwest tend to be highly fragmented. There are 231 separate cities, townships, and villages in metro Detroit, each with their own policies and priorities. Municipal responsibilities like transportation, public safety, and economic vibrancy transcend local borders, and tackling structural challenges like deindustrialization and regional disinvestment require collective action. (…) Given the size of inner suburbs-some are as tiny as 1 mile square-the lack of inter-jurisdictional collaboration impedes the already limited capacity of small local governments to meet the challenges they face.” (Kohn, 2005)

“Metropolitan areas in the Midwest tend to be highly fragmented. There are 231 separate cities, townships, and villages in metro Detroit, each with their own policies and priorities. Municipal responsibilities like transportation, public safety, and economic vibrancy transcend local borders, and tackling structural challenges like deindustrialization and regional disinvestment require collective action. (…) Given the size of inner suburbs-some are as tiny as 1 mile square-the lack of inter-jurisdictional collaboration impedes the already limited capacity of small local governments to meet the challenges they face.” (Kohn, 2005)

Or ce n’est pas un aménageur comme le MDOT, représentant de l’état du Michigan, qui peut résorber les difficultés de Southwest Detroit. D’où sa stratégie de se décharger vers d’autres institutions des responsabilités que plusieurs acteurs aimeraient lui faire porter.

It is not up to city planners such as MDOT, representing the State of Michigan, to find some way of resolving Southwest Detroit’s difficulties. Thus its strategy to download the responsibilities, a number of parties would like to see them bear, onto other institutions.

Ce qui oblige à reconnaître que les compensations socio-environnementales ne résolvent pas les déficits institutionnels dans l’aménagement de l’espace urbain et la prise en compte de l’environnement. D’une part, elles ne sont qu’un outil complémentaire à d’autres pour instaurer une certaine justice environnementale. D’autre part, il faut agir sur plusieurs leviers pour atteindre une certaine efficacité.

For this reason, we must admit that social and environmental compensation cannot solve institutional deficits for urban planning and the taking into account of the environment. On one hand, such compensation can be considered as a complementary tool to institute a certain form of EJ. On the other hand, to reach a certain level of efficiency, several levers have to be used.

3.2 Les « community benefits » : un instrument de concrétisation de la citoyenneté environnementale (Dobson, 2005) ?

3.2. Are “Community Benefits” a tool to implement environmental citizenship (Dobson 2005)?

Les situations d’injustice environnementale ne sont pas tant des actes délibérés de racisme de la part des promoteurs ou des exploitants d’infrastructures, que le reflet de l’absence de réelle prise en charge des inégalités environnementales dans toutes leurs dimensions. Dans une ville comme Detroit, les iniquités environnementales sont le fruit à fois d’une ségrégation spatiale continue (consolidation de ghettos), d’un contexte socio-économique déprimé et d’une urbanité ségrégative (Massey, Denton, 1995).

Different environmental injustice cases cannot necessarily be considered as deliberate racist acts on behalf of developers or different project managers. Rather they reflect a lack of policy that would actually deal with environmental inequality at every level. In cities such as Detroit, environmental inequity is the consequence of continual spatial segregation (consolidating of ghettos), the depressed social and economic context and segregative urban structures (Massey, Denton, 1995).

La volonté de négocier des community benefits à l’occasion des projets urbains d’infrastructure participe d’un désir des communautés pauvres ou appartenant à des minorités d’être reconnues comme des interlocuteurs à part entière et les détenteurs d’un savoir local à intégrer dans les décisions. C’est pourquoi certains activistes réclament plus formellement un ‘droit à la ville’ qui octroie aux plus démunis le même accès au débat public que les usagers et les propriétaires de l’espace urbain et la possibilité de débattre d’une réallocation des maux et des biens environnementaux (Marcello, 2008).