Introduction

Introduction

Cet article analyse la violence socio-environnementale qui marque le déploiement spatial du capital en Amérique latine, en s’appuyant sur une étude du territoire et des corps à San Salvador, une agglomération en milieu rural de la province d’Entre Ríos (Argentine). « Capitale argentine » de la production de riz, la ville s’est développée par son inscription dans une chaîne agro-industrielle qui lie l’espace urbain à la campagne. C’est cette dialectique entre l’urbain et le rural qui m’intéresse ici, telle qu’elle se décline dans un modèle de production extractiviste, l’environnement jouant un rôle clé dans cette relation ville-campagne.

This article explores the socio-environmental violence implicit in the spatial mode through which capital is structured in the Latin American region by looking at the transformation of territory and bodies in San Salvador, a rural city located in the province of Entre Ríos (Argentina). Known as the “Argentinian capital” of rice production, the city expanded thanks to the articulation of the agro-industrial chain, linking the town with the countryside. In the article, I explore the rural-urban dialectic, under the parameters of the extractive model of production, emphasizing the role of the environment in the relation between the rural and the city.

Cet article reprend le concept de métamorphose proposé par Henri Lefebvre (1989) en l’appliquant au cas de pueblo fumigado[1]. Je me démarque ici des théories qui insistent sur l’érosion des différences entre l’urbain et le rural – une métamorphose planétaire – ou sur l’expansion d’un milieu urbain privé de son extérieur (Brenner, 2018) pour aborder ce concept comme un processus toxico-biologique où le rural devient le lieu de l’organisation de la ville (Santos, 1994). Afin de remettre en question le grand récit de l’urbanisation totalisante (Walker, 2015, p. 186), et de donner une place à « l’extérieur » non urbain comme au rapport conflictuel à l’urbain, je propose, dans cet article, l’étude d’une ville rurale, fondée sur le lieu, à travers laquelle j’examine la désolidarisation à l’œuvre entre le rural (au sens de l’habiter) et l’agricole, où la population locale est écartée du modèle de production agro-industriel sans pour autant échapper à ses répercussions toxiques.

The article returns to Henri Lefebvre’s metamorphosis (1989), applying it to the case of a pueblo fumigado[1]. Departing from theories which emphasize the erosion of urban and rural difference—a planetary metamorphosis—or the advancement of an urban without an outside (Brenner, 2018), I explore the concept of metamorphosis as a toxic-biological process where the rural becomes the locus of organization for the city (Santos, 1994). With the intention of challenging a narrative of totalizing urbanization (Walker, 2015, p. 186) and giving space to the non-urban “outside” as well as its conflictual relation with the urban, I present a place-based study of a rural-city where I explore the uncoupling relation between the rural (as inhabitancy) and the agricultural, where the local population becomes disentangled from the agribusiness production model, but remains entangled in its toxic extensions.

Afin de prendre en compte les multiples transformations du rural, je reviends d’abord sur la littérature consacrée à la campagne mondialisée ou global countryside (Woods, 2007), en m’appuyant sur des travaux portant plus particulièrement sur les évolutions propres aux villes rurales industrielles (Teubal, 2001 ; Gras et Hernandez, 2013 ; Cimadevilla et Carniglia, 2009 ; Albaladejo, 2009, etc.) du Sud global. À la lumière de ces travaux, je problématise l’hypothèse de Christophe Albaladejo (2009) selon laquelle l’agroville est caractérisée par des modes de vie de plus en plus dissociés du modèle productif. Toutefois, du point de vue environnemental, ceux-ci sont à mon sens liés par le même environnement toxique.

In order to acknowledge the multiple transformations of the rural, I return to the literature of the global countryside (Woods, 2007), drawing on work that looks at specific developments in industrial rural-cities (Teubal, 2001; Gras and Hernandez, 2013; Cimadevilla and Carniglia, 2009; Albaladejo, 2009; etc.) in the Global South. Reflecting on this work, I problematize the premise proposed by Christophe Albaladejo (2009) that under the agrocity, modes of living become dissociated from the productive model. However, from an environmental perspective, I understand that both are still tied together through the toxic environment.

Je cherche ensuite à démontrer que cette complexe situation socio-environnementale est indissociable de l’héritage colonial du développement de la ville rurale, en analysant son déploiement spatial dans la campagne argentine ainsi que sa forme émergente d’agroville associée au mode de développement extractiviste (Gras et Hernandez, 2013). Enfin, faire de la dimension socio-environnementale un agent actif de cette dialectique permet d’étudier comment la transformation de l’environnement régule les dynamiques d’habitation (Machado, 2015) et constitue une forme spécifique de vie rurale moderne liée à des géographies extractivistes.

I explain this socio-environmental entanglement as part of the colonial legacy of the development of the rural-city, discussing its spatial formation in Argentina’s countryside, as well as its emerging form as an agrocity associated with the extractive mode of development (Gras and Hernandez, 2013). Finally, by including the socio-environmental dimension as an active agent in this dialectic, I aim to show how the transformation of the environment functions regulating the dynamics of inhabitancy (Machado, 2015) and constituting a specific form of modern rural living tied to extractive geographies.

Cet article souligne la manière dont, à l’aune de l’extractivisme, la dialectique entre l’urbain et le rural, au lieu d’aller vers un modèle d’urbanisation planétaire (Brenner, 2018), génère un nouvel agencement spatial colonial marqué par la création de « zones de sacrifice » (Svampa, 2008) dans la refonte des espaces ruraux dans la mondialisation (Woods, 2007 ; Santos, 1994). Ainsi, ces « villes rurales », ou plus précisément ces agrovilles, deviennent des points cruciaux dans lesquels la transformation radicale de l’environnement rural se fait patente, manifestant l’imbrication de l’humain et du non-humain dans le capitalisme extractiviste. Dans cette dialectique, comme l’écrit Milton Santos, « la ville locale cesse d’être une ville dans la campagne et devient la ville de la campagne » (ibid., p. 52 ; italiques de l’autrice).

The article explores how through an extractive lens, the dialectic between the rural and the urban, rather than progressing into a model of planetary urbanization (Brenner, 2018), creates a new colonial spatial disposition, with the formation of “sacrifice zones” (Svampa, 2008) in the remaking of rural places under globalization (Woods, 2007; Santos, 1994). In this way, rural cities, specifically agrocities, become critical points for exposing the radical transformation of the rural environment in the entanglement of the human and the non-human under extractive capitalism. In this dialectic, as Milton Santos defines it, “the local city ceases to be the city in the countryside and becomes the city of the countryside” (ibid., p. 52, italics added by the author).

On souligne l’apport de Maristella Svampa qui analyse cette formation spatiale comme « radicalisation de l’injustice environnementale » (2014). La notion de justice environnementale « constitue pour l’Amérique latine l’antécédent le plus direct, en termes conceptuels et politiques, pour la justice spatiale » (Salamanca et Astudillo, 2016, p. 27). Au cours des trente dernières années, des populations en lutte au sein de conflits environnementaux associés à des projets extractivistes ont construit une critique radicale de ces formes de développement, cherchant à étendre les limites de ce qui peut être revendiqué comme droit (droit à la nature et dette écologique, par exemple), tout en contestant la notion même du développement.

Of relevance to this article, is how Maristella Svampa frames this spatial formation in terms of a “radicalisation of environmental injustice” (2014). The notion of environmental justice “constitutes for Latin America the most direct antecedent in conceptual and political terms for spatial justice” (Salamanca and Astudillo, 2016, p. 27). In the last thirty years, communities struggling with the emergence of new environmental conflicts associated with extractive projects have provided a radical criticism of the extractive matrix of development, aiming to expand the boundaries of what can be claimed as a right (the rights of nature and ecological debt, for example) while also disputing the meaning of development.

Au regard des enjeux du présent numéro thématique de Justice spatiale | Spatiale Justice, cet article montre qu’il est essentiel de considérer l’agentivité violente de la nature comme l’une des conséquences du mode extractif de production – lequel a non seulement un impact structurel sur les lieux et les relations, mais également sur les corps et les territoires. Ainsi, ce texte éclaire les impacts disciplinaires à la fois sociaux et spatiaux de la transformation de l’environnement à mesure que les villes sont converties en des zones de sacrifice – lieux où la mort est prévisible.

Considering the focus of this special issue of Justice spatiale | Spatiale Justice, the article shows that we need to consider the violent agency of nature as one result of the extractive mode of production that has a structural impact on places and relations as well as on bodies and territories. As such, the analysis reflects on the transformation of the environment and its disciplinary social and spatial implications as towns are converted into sacrifice zones, places where death is expected.

Cadre théorique

Theoretical framework

Dans une perspective décoloniale, je considère le modèle de développement extractiviste tourné vers l’exportation (Gudynas, 2009 ; Svampa, 2012 ; Martin, 2021) comme une forme de violence coloniale à la fois sociale, écologique et politique qui s’exerce à la croisée de l’urbain et du rural, particulièrement dans la refonte de villes ancrées dans le rural comme San Salvador. Dans ce mode de développement, le contrôle et la domination sur la nation sur la nature, et l’extraction des ressources induisent, d’une part, des profits colossaux pour les producteurs et une forte expansion urbaine, et, de l’autre, la transformation de la ville en poids mort environnemental, un endroit où les formes locales de vie, de reproduction sociale et de durabilité environnementale cessent d’être pertinentes dans la production de l’espace et l’aménagement du territoire.

Informed by a decolonial perspective, I address the export-oriented extractive model of development (Gudynas, 2009; Svampa 2012; Martin, 2021) by conceptualizing it as a form of colonial violence that extends across social, ecological, and political aspects in the dialectics of rural and urban life, particularly insofar as it reshapes rural cities, such as San Salvador. Under this mode of development, the control, domination and extraction of resources result, on one hand, in huge profits for producers and in city expansion; while, on the other, they transform the city into an environmental liability, where local forms of living, social reproduction and environmental sustainability become irrelevant to the production of space and territorial planning.

J’applique ici la notion de violence environnementale de Rob Nixon (2011) au contexte des transformations des villes rurales, afin d’aborder les taux élevés de mortalité et la dégradation de la santé des habitants sous l’angle du déplacement. Bien qu’à San Salvador la population soit peu marquée par la mobilité et les départs, il ne s’en agit pas moins d’un cas de violence né du déplacement. Pour Nixon, c’est une forme de violence qui agit hors de vue, une forme de destruction à pas lents, fragmentée dans le temps et l’espace. Elle devient une violence d’usure qui n’est jamais reconnue comme telle (ibid., p. 2). La violence environnementale peut être comprise comme une forme de « déplacement sans mobilité », un « déplacement stationnaire » (ibid., p. 19 et p. 42), ce n’est pas un conflit armé ou une catastrophe naturelle qui force les habitants à partir, mais la pollution qui, comme le montre cet article, érode peu à peu l’état des villes et leur viabilité pour en faire des lieux hostiles engendrant des maladies ou, en fin de compte, la mort.

I bring Rob Nixon’s notion of environmental violence (2011) to the context of rural cities’ transformations, explaining high rates of death and the degrading of people’s health in terms of displacement. While the case of San Salvador shows us people neither moving nor leaving the city, it remains a case of displaced violence. As Nixon explains, this is a form of violence that occurs out of sight, a case of delayed destruction that is dispersed in time and space. It develops as a violence of attrition that is not recognized as violence at all (ibid., p. 2). Environmental violence can be understood as a form of “displacement without mobility” or “stationary displacement” (ibid., p. 19; p. 42), where it is not an armed conflict or natural disaster that forces villagers to move, but, as I explore in this article, pollution that gradually erodes the conditions and sustainability of cities, converting them into hostile places causing illness or, eventually, death.

En outre, je cherche à instaurer un dialogue entre la violence environnementale de Nixon et la notion de métamorphose toxique pour interroger la façon dont cette forme de violence s’inscrit dans l’expérience quotidienne des habitants. Dans les pueblos fumigados, la métamorphose du quotidien est imperceptible, elle opère à la manière d’un processus lent et silencieux qui se propage dans l’air, l’eau et le sol, dans les organismes vivants. La dialectique entre l’urbain et le rural, en incluant les corps affaiblis et contaminés qui habitent la ville polluée, acquiert un sens nouveau.

Furthermore, I put Nixon’s environmental violence in dialogue with toxic metamorphosis to explore how this form of violence is incorporated in people’s quotidian experience. In pueblos fumigados, the metamorphosis of everyday life goes unnoticed, operating as a quiet and slow biological process that occurs in the air, land and water as well as in living bodies. In this way, the dialectics between the urban and the rural acquire new meaning, incorporating the degraded and contaminated bodies that inhabit the polluted town.

Méthodologie

Methodology

Ce travail de recherche repose sur une méthode qualitative et une approche ethnographique, dans laquelle j’historicise le rapport entre la ville et l’espace rural en m’intéressant à la manière dont évoluent les dynamiques de proximité et de distance selon les différents modes de production. À cette fin, j’ai passé trois mois (en 2021) dans la région de la ville de San Salvador, située dans la zone extra-pampéenne d’Argentine (région de Mésopotamie).

The research used a qualitative method with an ethnographic approach where I historicize the relationship between the city and the rural, focusing on the changing dynamics of proximity and distance along different modes of production. During the course of this research, I spent three months (2021) in the area of the city of San Salvador, located in the extra-Pampean zone of Argentina (Mesopotamian region).

San Salvador correspond au modèle des villes rurales de la province d’Entre Ríos et de la plupart des villes prospères du centre géographique du pays. La place principale de la commune, la fierté de la ville, en marque le centre : elle est propre, pimpante, bien éclairée. Tous les événements publics s’y déroulent ; les habitants en font chaque jour le tour en voiture afin de voir et d’être vus par tout le monde en ville.

San Salvador replicates the model of rural towns in the province of Entre Ríos and most well-off towns in the geographical center of the country. The town square is the pride of the city and marks its center—it is clean, tidy, and well illuminated. All public events take place there and people drive their cars around it daily to see and be seen by everyone in the town.

Dans la vie de tous les jours, les habitants sont habitués à vivre à côté des rizeries[2] et d’épousseter leurs habits après les avoir étendus dehors à sécher. Pour la plupart d’entre eux, les particules en suspension dans l’air et la contamination de l’eau ou du sol ne constituent pas un sujet d’inquiétude. Bien que personne ne boive l’eau du robinet, la population de San Salvador ne considère pas l’environnement local comme dangereux. C’est paradoxalement grâce à la COVID-19 que de nombreuses personnes ont découvert que le port du masque améliorait sensiblement leur respiration. Les habitants qui expriment ouvertement leur intérêt pour l’écologie et l’environnement sont perçus avec méfiance : ils sont qualifiés de « gauchistes » ou de « gens de la ville » qui ne comprennent rien à la vie rurale et à au mode de production agricole. Or la plupart de mes enquêtés ont mentionné connaître quelqu’un, qui, lors des dix dernières années, a eu un cancer ou en est mort, lorsqu’ils n’ont pas eux-mêmes été touchés par la maladie. Au cours de mon travail de terrain, j’ai conduit quatorze entretiens avec différents acteurs clés de la ville – producteurs ruraux, propriétaires de rizeries, ouvriers, riverains exposés à la pollution, propriétaires terriens et militants écologistes. Je les ai interrogés sur leurs perceptions de la pollution au quotidien et sur les éventuels changements intervenus dans leurs habitudes ou attitudes à la suite du rapport sur l’environnement et la santé (démontrant la gravité de la pollution à San Salvador) paru en 2016. L’un des objectifs de ma recherche était de produire une carte collective des espaces, secteurs ou trajets évités, mais au dire des enquêtées, la ville était dans un « grand nuage » et il n’était pas possible de faire de distinctions significatives entre quartiers ou zones de la ville (et de ses alentours).

In everyday life, people are used to living next to mills[2] and to cleaning the dust off their clothes after hanging them out to dry. Most people are not concerned about the dust in the air or the contamination of water or land. While people do not drink tap water, no one considers the environment of San Salvador to be dangerous. Ironically, during the pandemic, many people discovered that using a mask greatly improved their breathing. People who are openly concerned by ecology and the environment are perceived with distrust and framed as “leftists” or “urbans”—people who do not understand rural living and the agricultural mode of production. However, most of the people interviewed knew or had lost someone due to cancer in the last 10 years, or they were sick themselves. During the fieldwork, I carried out 14 interviews with different relevant actors from the city—rural producers, mill-owners, workers, people affected by pollution, landowners and environmental activists—during which I asked them about their perceptions of living with pollution and if there were any changes to their habits and attitudes following the results of an environmental and health report (which offered evidence of the contamination in San Salvador) published in June 2016. One of the aims of my research project was to develop a collective map of avoided zones, areas, paths and walks, but people said that it was all “a big cloud” and that marked distinctions could not be made between neighborhoods or zones in the city (and beyond).

Figure 1 : image nocturne de l’une des rizeries situées à San Salvador © Julian Paltenghi (avril 2020)

Figure 1: A nocturnal image of one of the mills located inside San Salvador © Julian Paltenghi (April 2020)

Pourquoi San Salvador ?

Why San Salvador?

Mon intérêt pour San Salvador est né d’une manifestation organisée fin 2013, la plus grande à avoir jamais eu lieu sur place (1 500 manifestants pour 13 000 habitants), afin de pousser la municipalité à prendre des mesures face au taux élevé de pathologies au sein de la population. Selon les données de l’association Todos por Todos [Tous pour tous], un petit groupe structuré de voisins travaillant avec le réseau Red de médicos de pueblos fumigados[3], 249 personnes sont mortes à San Salvador entre 2009 et 2013, dont 108 de cancer[4] (ANRED, 2015). Après plusieurs demandes de l’association, la municipalité a accepté de réaliser une étude environnementale et épidémiologique pour déterminer les sources de dégradation de la santé de la population locale. Les craintes des riverains portaient principalement sur le nuage de poussière causé par les rizeries implantées dans la ville et par l’activité agro-industrielle qui ne cesse de s’étendre tout autour.

My interest in this town emerges from its largest ever protest by the end of 2013 (1,500 people in a town of 13,000) that was organized to demand a response from the municipality for the high rate of disease occurring in the city. According to information from the organization “Todos por Todos” (All for All)—a small group of organized neighbors, which worked together with the network “Red de médicos de pueblos fumigados”[3]—249 people died in San Salvador from 2009 to 2013, with 108 of those being victims of cancer[4] (ANRED, 2015). After several requests from this organization, the municipality agreed to conduct an environmental and epidemiological study to determine the sources of the health degradation impacting the community. The main suspicions of the neighbors pointed to the dust cloud generated by mills spaced out along the city and the expanding agroindustrial activity surrounding the city.

Deux études ont été effectuées en 2014-2015. La première, à visée environnementale, concerne la concentration de pesticides observée à partir de prélèvements environnementaux ; elle a été coordonnée par la faculté des Sciences exactes de l’université de La Plata sous la direction de Damian Marino. La seconde est une enquête épidémiologique, réalisée conjointement par la faculté des Sciences médicales et le département de Santé socio-environnementale de l’Université nationale del Rosario. Deux rapports en émanent : une analyse du profil de morbi-mortalité de la population (UNR, 2016) et un rapport environnemental (UNLP, 2016).

The two studies were conducted during 2014-2015. One was an environmental study of the concentration of pesticides in environmental samples (coordinated by the Faculty of Exact Sciences at the Universidad de La Plata and directed by Damian Marino), and the other was an epidemiological survey of morbimortality (organized by the Faculty of Medical Sciences from the Universidad Nacional del Rosario, Department of Socioenvironmental Health of the University of Rosario). Two reports were provided: a Profile of Morbidity and Mortality of the Population (UNR, 2016) and an Environmental Report (UNLP, 2016).

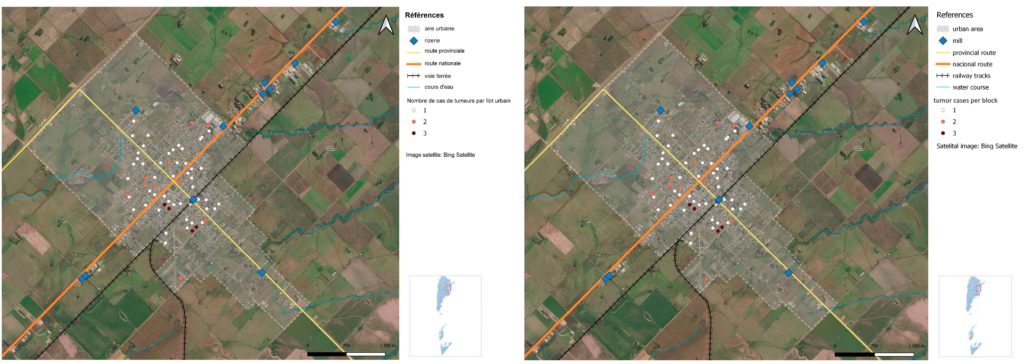

Le rapport environnemental (UNLP, 2016) note la présence historique de trente et un pesticides actuellement en usage en agriculture dans l’ensemble des échantillons testés (eau, air et sol). L’étude épidémiologique sur la morbi-mortalité démontre quant à elle que la principale cause de mortalité au cours des quinze dernières années est le cancer, et plus particulièrement le cancer du poumon (UNR, 2016, p. 17). Si les affections les plus courantes sont les maladies cardiovasculaires (selon les tendances générales de la région), elles sont suivies de près par les pathologies respiratoires et allergiques (ibid., p. 13). En matière de distribution spatiale, on dénombre 84 cas de cancer diagnostiqués entre 2000 et 2014 dans 80 ménages (ibid., p. 17). La figure 2 permet de visualiser l’échelle de la ville et de son environnement rural, et situe les cas de cancer et la répartition des rizeries.

The Environmental Report (UNLP, 2016) determined the historical presence of 31 pesticides of use and of current agricultural relevance to all the environmental matrixes tested (water, air and soil). The epidemiological survey on morbidity and mortality revealed that the main cause of death in San Salvador over the last 15 years is cancer, specifically, lung cancer (UNR, 2016, p. 17). The most common chronic disease was cardiovascular (following the general tendency of the region), but this was followed by respiratory and allergic pathologies (ibid., p. 13). In terms of geospatial distribution, it was noted that in 80 households there were 84 cases of cancer diagnosed between 2000 and 2014 (ibid., p. 17). The figure 2 is a map that gives a picture of the scale of the city and its location in a rural area. It combines the distribution of tumor cases, and the distribution of the mills within the urban area.

Figure 2 : Cas de tumeurs, emplacement des rizeries et aire urbaine. Ville de San Salvador, province d’Entre Ríos, Argentine. Conception : Maria Fernanda Zaccaría, données communiquées par le rapport sur le profil de morbi-mortalité de San Salvador, Entre Ríos (UNR, 2016) et les habitants Nestor Luis Sarli et Richard Miguel Angel (2011)

Figure 2: Tumor cases, mills location and urban area. San Salvador city, Entre Ríos province, Argentina. Elaboration by Lic. Maria Fernanda Zaccaría, data provided from Morbidity and mortality profile report of San Salvador, Entre Ríos (UNR, 2016) and neighbors Nestor Luis Sarli and Richard Miguel Angel (2011)

Pour résumer, les études ont réussi à résoudre les principaux obstacles auxquels font face les communautés rurales en quête de justice environnementale : obtenir des données empiriques sur la corrélation entre la hausse des pathologies et la dégradation et la toxicité de l’environnement. Or, après que les résultats des deux études ont été rendus publics, la situation n’a pratiquement pas évolué. En dépit de leur portée, ils n’ont eu aucune incidence sur le modèle agro-industriel[5] ni sur les modes de vie des habitants. Les preuves matérielles apportées ont eu peu d’effet, sinon l’application de régulations déjà établies, assorties de quelques nouvelles mesures proposées par la municipalité[6]. Parallèlement, de nombreuses personnes connues pour s’être impliquées dans la mobilisation ont subi des conséquences négatives. Pour les gens interrogés ayant pris part à la manifestation, rien n’a changé : les habitants sont revenus à leur vie de tous les jours.

In sum, the studies managed to resolve the main limitation of rural communities demanding environmental justice: to obtain empirical evidence of the correlation between the increase of disease and the degradation and toxicity of the environment. Nevertheless, after the results of the studies were made public, very little changed. The forcefulness of the studies’ results had no impact on the agribusiness model[5], nor the lifestyle of local inhabitants. The hard evidence provided achieved little more than enforcing regulations that had already been established along with a few new responses from the municipality.[6] Simultaneously, many of the people known to be involved in the campaigning were negatively impacted. As interviewees involved in the protest noted, after the social upheaval dissipated, nothing changed and people returned to their daily routine.

Les racines de la ville de San Salvador : proximité spatiale et immobilité

The roots of the city of San Salvador: spatial proximity and immobility

Après la parution de l’étude socio-environnementale (UNLP, 2016), la rizerie la plus emblématique de la ville, symbole d’industrialisation et de prospérité, a occupé une place plus ambivalente. L’image du champignon de poussière sans cesse croissant, incarnation même de la productivité, a commencé soudain à se heurter à l’image de la poussière comme agent principal de la pollution de la ville et de ses habitants :

With the results of the socio-environmental study (UNLP, 2016), the iconic mill, an image of industrialization and prosperity, started to occupy a more ambivalent position. The image of the growing dust mushroom as a sign of productivity started to clash with imagery of the dust as the main agent of contamination in the town and of its people:

« Et comme ça faisait partie du folklore, la poussière, le paysage, à partir de là les gens ont commencé à se rendre compte, à manifester, à exiger qu’il y ait moins de poussière. » (militante locale)

“And as it was part of the folklore, the dust, the landscape and from there people began to become aware and people began to protest and demand that this dust be reduced.” (local activist)

Dans une ville fondée pour fournir des produits agricoles, la relation de production est au cœur du sens commun. L’identification de la ville sansalvadoreña à son rôle dans la production rizicole est telle qu’elle a obtenu le titre de capitale nationale du riz en 1951, lors de la première célébration organisée par la ville. Mais les changements dans le mode de production ont matériellement affecté les représentations et la perception de l’innocuité des rizeries. Un développement lié à des objectifs de fonctionnalité et d’aménagement socioterritorial révèle aujourd’hui une complexité insoupçonnée il y a encore quinze ans. La relation vertueuse de productivité entre usine et ville, qui visait à accroître la proximité, de façon à ce que les ouvriers vivent à côté de leur lieu de travail, pour éviter les retards et préserver leur énergie (qu’ils marchent ou prennent les transports en commun), s’est en fait inversée, révélant un impact important sur l’environnement et la santé publique. La poussière devient une trace visible venue des champs, transformée en ville et elle fait partie du paysage local.

For a city founded as a provider of agricultural products, the productive relation is organizer of common sense. Such is the identification between the sansalvadoreña city and its role in production that it earned the title of the national capital of rice in 1951, with the first celebration organized by the city. But, since then, the changes in the mode of production have led to the material side of this representation affecting perceptions of the mills’ innocuousness. What was developed under the premise of functionality and socio-territorial planning is today revealing a complexity not considered until 15 years ago. The virtuous relationship of productivity between the mill and the city that had aimed to increase proximity to the mills, so that workers could be as close as possible to their workplace, avoiding unnecessary delays and wasted energy (in the form of long walks or use of public transport) has been inverted, revealing the significant impact on the environment and public health. The dust becomes a traceable element from the fields which is processed in the city and becomes part of the local landscape.

« C’est devenu visible, qu’elle [la poussière] a toujours été la vedette de la ville. Autour des rizeries, on a trouvé des pesticides, dans l’air, dans l’eau, partout. » (militant local et biologiste)

“it became visible, what [the dust] was always the vedette [star] of the city. All around the mills were found pesticides, in the air, in the water and all that.” (local activist and biologist)

La proximité géographique des rizeries, des sites de stockage et de l’activité agricole qui entourent la ville témoigne de l’imbrication de ces deux espaces dans la vie économique, sociale et politique de San Salvador. Comme le décrit un militant local :

This spatial proximity between the mills, the deposits and the agricultural activity surrounding the city reveals the imbrication of both in organizing the economic, social and political life of the city of San Salvador. This was described by a local activist:

« c’est une ville qui est considérée comme un prestataire de services agricoles, ce n’est pas comme Concordia qui a un fleuve […], une architecture, un port, des espaces naturels, un barrage […], qui en gros a une histoire. San Salvador est une ville qui est née pour fournir des services agricoles. On a construit une voie ferrée, une usine, et on a commencé à exporter. Point barre. » (militant local et biologiste)

“It is a city that is considered a provider of agricultural services, it is not like Concordia that has the river […] that has architecture, a port, nature, a dam […] basically which has history. San Salvador was born as a city providing agricultural services. It built a railway and started to have a mill and began to export. Full stop.” (local activist and biologist)

Cette citation met en évidence la richesse des caractéristiques ainsi que du passé attribués aux autres villes de la région, et souligne ainsi la sujétion totale du contexte local au capital dans la structuration de l’espace et des rapports socio-économiques. Privée des particularités géographiques et de l’importance politique dont jouissent les autres villes de la province, San Salvador définit principalement son identité au regard de sa production :

This quote emphasizes the richness of characteristics and histories attributed to other cities in the area, thereby highlighting the local context of full subjection to capital in the structuring of space and socio-economic relations. Lacking any other physical feature or political relevance (to keep in mind) in comparison to other towns or cities in the province, the identity of the city is mostly connected to its production:

« […] les habitants de San Salvador défendent l’identité rizicole de leur territoire, mais à quel prix ? Nous sommes là aussi, nous avons décidé d’être là et nous avons décidé d’y rester, et ce n’est pas sans conséquences. » (employé municipal)

“[…] the people in San Salvador defend their place of rice identity, what is the cost? But we are also here, we decided to be here and we decided to stay here and it has certain consequences.” (municipal worker)

Dans la partie suivante, j’analyse la dialectique rural-urbain qui se joue dans le cadre du développement extractif, en me concentrant sur la « ville rurale » comme espace crucial d’organisation de l’économie extractiviste.

In the following section, I analyze the rural-urban dialectics at play under the extractive matrix of development, focusing on the rural-city as a critical space in organizing the extractive economy.

Les villes rurales du Sud global : la modernisation des espaces ruraux

Rural cities in the Global South: the modernization of rural spaces

San Salvador est une ville née du processus de modernisation des géographies postcoloniales, fondé sur la violence coloniale et la constitution de la propriété privée. L’expansion du chemin de fer et l’ouverture de routes desservant la ville, l’urbanisation des communes avoisinantes et l’arrivée des usines ou des rizeries – comme c’est le cas ici – forment la trame d’un récit bien connu qui, à la fin du XIXe siècle et au début du XXe siècle, est devenu un modèle de développement rural en Amérique du Sud. Le rapport des Sansalvadoreños à la terre est à la fois utilitaire et affectif. C’est une ressource destinée à produire de la richesse, mais aussi un lieu d’habitat et un type de relation inscrit dans le binôme économie-écologie – le non-humain, un « autre » transformé par la production, l’exploitation et l’accumulation (Moore, 2010). Les mutations actuelles du monde rural dans la région, à mesure qu’elles progressent au XXIe siècle et s’inscrivent dans le cadre existant de la reprimarisation des économies de la périphérie, peuvent, à mes yeux, être appréhendées dans le contexte plus large de la « campagne mondialisée », c’est-à-dire :

San Salvador is a town born out of the modernizing process of postcolonial geographies, grounded in colonial violence and the formation of private property. The expansion of the railroad and the opening of routes to the city, the urbanization of townships and the arrivals of factories or mills (as is the case with San Salvador) are a classic tale, becoming a model for rural development in South America at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. The relationship of the Sansalvadoreños with land is utilitarian and affectionate. It is a resource meant to provide wealth as well as a home, one type of relationship set up in the economy-ecology binominal—the non-human, an alien transformed through production, exploitation and accumulation (Moore, 2010). Advancing into the 21st century and under the current trend of reprimarization of peripheral economies, I frame the contemporary rural transformation in the region within the larger context of the “global countryside”:

« Un milieu rural traversé de réseaux multiples, évolutifs, emmêlés et dynamiques qui relie le rural au rural et le rural à l’urbain, mais avec une plus grande intensité des processus de mondialisation et des interconnexions mondiales dans certaines localités rurales que dans d’autres, dont découle une répartition différentielle du pouvoir, des opportunités et de la richesse dans l’espace rural. » (Woods, 2007, p. 491)

“A rural realm constituted by multiple, shifting, tangled and dynamic networks, connecting rural to rural and rural to urban, but with greater intensities of globalization processes and of global interconnections in some rural localities than in others, and thus with a differential distribution of power, opportunity and wealth across rural space.” (Woods, 2007, p. 491)

Mais afin de contextualiser la métamorphose de San Salvador, je dois d’abord revenir aux développements conceptuels menés sur les villes rurales de la région. Le concept de ville rurale, dans le Sud global, a été élaboré à partir de plusieurs approches auxquelles correspondent diverses appellations comme « agroville » (« agrociudad » en espagnol, Albaladejo, 2009), « rurbain[7] » (« rururbanidad » en espagnol, Cimadevilla et Carniglia, 2009) ou « nouvelles ruralités » (Teubal, 2001). Ce que ces différents développements conceptuels et théoriques mettent au jour, c’est la transformation du rapport entre l’urbain et le rural, et plus précisément, la modernisation des territoires ruraux. Tous ces termes ont pour dénominateur commun de renvoyer à une transformation spatiale, sociale, matérielle et symbolique, connectée au mode de production agricole. S’ils ne s’opposent pas les uns aux autres, ils s’attachent cependant à des aspects différents de cette transformation. Appliqué à la « périphérie du monde » (Cimadevilla et Carniglia, 2009, p. 5), le concept de rurbain propose tout d’abord de mettre en évidence les dynamiques rurales à l’œuvre dans les espaces urbains, déjouant ainsi théoriquement l’affirmation d’Henri Lefebvre sur l’urbanisation de la vie sociale. Les processus de rurbanisation (c’est-à-dire de ruralisation de la ville) sont donc mobilisés pour explorer les marges et la marginalité de la modernité, en prêtant attention aux acteurs que l’on a exclus de la vie rurale – par exemple les paysans devenus acteurs du recyclage urbain utilisant leurs chevaux comme véhicules à traction animale pour leurs circuits de collecte (ibid., p. 11-13). Le concept de nouvelle ruralité (Teubal, 2001) souligne par ailleurs l’expansion verticale et horizontale dans la création d’espaces contrôlés par de grandes sociétés dans le rural, vecteur de l’intégration de ce dernier dans l’émergence du système agro-alimentaire mondialisé. Il s’agit désormais, suivant Miguel Teubal, d’une « agriculture sans agriculteurs », façonnée par l’usage des nouvelles technologies associées à la production généralisée de cultures transgéniques et à l’exclusion massive des agriculteurs et paysans hors de la sphère agricole (Giarraca et Teubal, 2009, p. 157). Enfin, la notion d’agroville, inventée par le géographe Christophe Albaladejo, désigne les villes qui fournissent des services essentiels à la modernisation de la campagne, par exemple des intrants agricoles, une assistance technique ou des services bancaires, etc.

But in order to situate the metamorphosis of San Salvador, I return to the conceptual developments of rural-cities developed in the region. The concept of rural cities in the Global South has been elaborated by several perspectives and has been given diverse names such as “agrocity” (in Spanish: “agrociudad”, my translation; Albaladejo, 2009), “rurban”[7] (in Spanish: “rururbanidad”; Cimadevilla and Carniglia, 2009), or “new ruralities” (Teubal, 2001). What these different theoretical and conceptual developments highlight is the transformation between the urban and the rural and, more specifically, the increasing modernization of rural spaces. As a common denominator, all of these concepts refer to a spatial, social, material and symbolic transformation, all intersected by the agricultural mode of production. While the terms are not in opposition to one another, they focus on different aspects of this transformation. On one hand, the concept of rurban developed for the “world periphery” (Cimadevilla and Carniglia, 2009, p. 5) proposes to unveil rural processes that take place in urban spaces theoretically defying Lefebvrian claims about the urbanization of social life. Thus, processes of rurbanization, (i.e., processes of ruralization of the city) are discussed to explore the margins and the marginality of modernity, looking at the expelled actors of rural life—peasants, for example, that become urban recyclers using horses as animal-powered vehicles for their searching circuits (ibid., p. 11-13). The concept of new rurality (Teubal, 2001), on the other hand, emphasizes vertical and horizontal expansion in the creation of corporate spaces in the rural sphere as part of its integration into the emerging global agri-food system. Miguel Teubal describes it as a new “agriculture without farmers” shaped by the use of new technologies associated with the widespread production of transgenic crops and the massive expulsion of farmers and peasants from agriculture (Giarraca and Teubal, 2009, p. 157). Finally, geographer Christophe Albaladejo coins the term “agrocity”, as cities that provide the fundamental services for the modernization of the countryside, such as agricultural inputs, technical advice and banking services, etc.

« Ce sont également des centres où un nouveau mode de vie “moderne” est consommé et inventé […]. Ces campagnes, à partir du moment où elles sont essentiellement définies par l’activité agricole et plus encore par la dimension “production” de cette activité, vont être plus communément désignées sous le nom “el campo”. » (Albaladejo, 2013, p. 10)

“They are also centers of consumption and invention of a new ‘modern’ way of life […] This countryside, from the moment when it becomes essentially defined by the agricultural activity and even more by the ‘production’ dimension of this activity, will be more commonly called by the word ‘el campo’.” (Albaladejo, 2013, p. 10)

Dans cette nouvelle organisation spatiale du rural, « el campo » (ainsi nommé pour définir la terre comme une ressource naturelle, et non comme le fondement matériel de la reproduction sociale) s’impose comme un terme central pour définir le rural par sa fonction productive, à la différence de la période coloniale où l’estancia[8] était au centre de la vie sociale : « [il] n’y a plus de campagne, il n’y a plus d’espaces ruraux, il y a “un campo”, il y a des villages, et il y a des villes ![9] » (Albaladejo, 2013, p. 11; italiques de l’autrice). Ce que met en évidence le modèle de l’agroville, c’est un processus de séparation entre des modes de vie et des modes de production.

In this new spatial organization of the rural, “el campo” (named as such to frame land as a natural resource—but not the material basis for social reproduction) stands out as a key term to define the rural through its productive function, in contrast to the postcolonial period where the estancia[8] was central to social life: “There is no more countryside, there are no more rural spaces, there is el ‘campo’ and there are towns and cities!”[9] (Albaladejo, 2013, p. 11, my italic). What is highlighted in the agrocity model is a process of separation between forms of living and the mode of production.

Carla Gras et Valeria Hernandez (2013) reprennent la notion d’agroville d’Albadejo pour l’aborder sous l’angle du mode de production extractiviste. Elles font remonter les débuts de cette période aux années 1990, caractérisées par les politiques d’ajustement structurel et la libéralisation du marché. Dans le secteur agricole, l’Argentine s’ouvre entièrement aux avancées biotechnologiques lorsque le soja transgénique est autorisé en 1996. Dans leur ouvrage, El agro como negocio, Gras et Hernandez explorent le développement territorial de l’agro-industrie, soulignant la dissociation entre vie urbaine et réseau de production :

Carla Gras and Valeria Hernandez (2013) update Albaladejo’s agrocities under the extractivist mode of production. They inaugurate this period in the 1990s, with the policies of structural adjustment and the liberalization of the market. Specific to the agricultural sector in 1996, Argentina fully embraced emerging biotechnological improvements with the approval of the transgenic soybean. In their book, El agro como negocio, Gras and Hernandez explore the territorial development of the agribusiness, highlighting the dissociation between urban life and the productive network:

« Les dynamiques de fragmentation par le bas et de concentration par le haut, de même que la désolidarisation entre l’activité de production et les logiques propres aux différents piliers du modèle agro-industriel (financier, technologique et fiduciaire) favorisent et perpétuent en effet la dissociation susmentionnée. La principale conséquence, c’est un divorce entre l’insertion productive des acteurs dans le tissu agricole et le mode de sociabilité tel qu’il s’est construit dans les villes rurales. » (Gras et Hernandez, 2013, p. 51).

“In effect, both the dynamics of fragmentation from below and concentration from above, as well as that of the decoupling between productive activity and the intrinsic logics of various pillars of the agribusiness model (financial, technological, fiduciary) promote and perpetuate the aforementioned dissociation. The main consequence is the divorce between the productive insertion of the actors in the agricultural fabric and the mode of sociability built in rural towns.” (Gras and Hernandez, 2013, p. 51)

Le modèle agro-industriel se manifeste ainsi sur le territoire sous la forme d’une mise à distance, par un double processus : d’une part, à travers une différenciation de l’agricole et du rural local et, de l’autre, par une distinction de l’urbain et du productif. En effet, l’agricole est traité comme un champ de production, un site d’extraction de valeur ; celui-ci finit par être mis à l’écart de la « ville rurale » et de l’espace de socialisation qu’elle constitue. Par ailleurs, le réseau urbain et la vie urbaine du secteur de l’agrobusiness sont également dissociés du système de production.

Thus, the territorial expression of the agribusiness model presents a distancing, expressed in a double process: first, through a differentiation between the agricultural and the local rural, and second, with the separation of the urban from the productive. On one hand, the agricultural is treated as a production field and a site of value extraction; this becomes distanced from “the rural town”, which is the space of socialization. On the other hand, the urban network and the urban living of the agribusiness sector are also dissociated from the production system.

L’« agroville » comme zone de sacrifice : distante, mais proche

The agrocity as a sacrifice zone: distant but close

Dans le cas de San Salvador, la désolidarisation implicite qui accompagne la constitution de l’agroville s’est traduite par un processus simultané de dépaysannisation, caractérisé par la disparition rapide des ouvriers agricoles et de leur savoir-faire dans les champs (Villulla et al., 2019), ainsi que par l’accroissement de la population urbaine, et donc des services. Cette dynamique a débuté dans les années 1950, avec l’arrivée de services et de la maintenance des engins agricoles (pour les rizeries et les infrastructures de stockage), s’est poursuivie avec l’essor des moyens de production destinés à l’agro-industrie (pesticides, transformateurs, matériel agricole, etc.) puis, à partir des années 1990, avec l’apparition de nouvelles formes de consommation, des cafés, des épiceries, des kiosques, et des centres de réparation et de vente de matériel technique, des écoles et des lycées, à proximité des établissements tertiaires. La ville s’est développée ainsi, se tournant davantage vers les services.

In the case of San Salvador, the decoupling implicit in the formation of the agrocity is expressed through a simultaneous process of depeasantization, characterized by the rapid loss in the fields of craft-based manual laborers (Villulla et al., 2019) as well as an increase in the urban population, associated with the increased presence of services. This started with the service and maintenance of rural machinery (for the mills and storage infrastructure) in the 1950s, followed by inputs for the agroindustry (pesticides, transformers, agricultural implements, etc.), and later by the appearance of new forms of consumption, with bars, cafes and kiosks, as well as technology shops, schools and high schools in proximity to tertiary institutions in the 1990s. The city expanded, becoming more service-oriented.

Mais contrairement à la fragmentation croissante du rural et de l’urbain annoncée par le modèle de l’agroville, le passage « del campo » aux principes de l’agro-industrie témoigne d’une continuité, plutôt que d’une démarcation manifeste, entre la ville et la campagne. La proximité géographique des rizeries par rapport à la ville et à la production agricole s’avère être non seulement une organisation spatiale obsolète pour l’agroville (et donc pour la dissociation qu’elle institue entre le productif et le spatial), mais aussi le cadre idoine pour la mise en place d’une zone de sacrifice. Cette forme d’organisation spatiale associe l’agroville aux champs agricoles du fait de son impact environnemental, dont la conséquence est un double processus, étroitement entremêlé, de destruction du territoire et de destruction du vivant (Svampa, 2014, p. 86). Dans le cas de San Salvador, cette prédisposition sacrificielle constitue un effet collatéral de l’expansion du modèle agro-industriel auquel est confrontée la population en raison de la pollution de l’air, du sol et de l’eau, laquelle est rendue manifeste par la présence des rizeries, mais aussi par les liens quotidiens qu’elle entretient avec l’agro-industrie.

But in contrast to the increasing fragmentation between the rural and the city proposed by the agrocity model, from an environmental perspective, the reorientation of “el campo” towards the principles of agribusiness started to expose a continuation, rather than the apparent demarcation between the city and the rural. The physical closeness of the mills to the city, as well as to agricultural production, appears not only as an obsolete sociospatial organization for the agrocity (and its productive and social dissociation), but as the optimal set-up for the formation of a sacrifice zone. This form of spatial organization connects the agrocity to the agricultural fields through its environmental liabilities, which implies a double and concatenated process of the destruction of territory and the destruction of life (Svampa, 2014, p. 86). In the case of San Salvador, this sacrificial disposition is established as a collateral effect of the agribusiness development model to which the population is exposed through the pollution of air, land and water, most visibly due to its proximity to the mills, but also through the daily closeness of its links to the agribusiness.

Avec l’essor du modèle agro-industriel, le corps humain se trouve ainsi exclu de la participation, pourtant indispensable, à la production agricole (urbaine ou rurale), sans pour autant cesser d’en subir les effets, et sans doute plus encore qu’avant. Une grande partie, voire la majorité des habitants de San Salvador, même en ayant un rôle indirect ou passif dans la production agro-industrielle, fait partie des victimes potentielles de cette dernière. Les corps et les territoires meurtris sont assimilés au prix à payer pour le développement, comme le décrit un habitant :

Through the development of the agribusiness model, people’s bodies are withdrawn from critical participation in agricultural production (whether urban or rural), yet they are still affected as much or more than before. Many, if not most, of the inhabitants of San Salvador, while having a deferred or passive role in agribusiness production, are potential victims of its presence. Diseased bodies and territories are assimilated as the cost of development, as described by an inhabitant:

« On va mettre la rizerie à côté des maisons ! Aujourd’hui, la plupart des rizeries sont sur le territoire urbain même, à côté de nos maisons, ce qui engendre un risque très élevé, et je pense que les gens… quand on prend l’habitude, quand on vit dans cette situation violente, les gens du coin ont tendance à minimiser. » (employé municipal)

“We are going to put the mill next to the house! Today, most of the mills are within the urban common land next to your house, that generates a very high social risk, and I think that people… When you get used to it, you live with this violent situation, the local people minimize it.” (municipal worker)

L’agroville est un format selon lequel le rapport entre l’urbain et le rural est, sur le plan de la production, de la symbolique et de l’habiter, plus divisé que jamais. D’une part, la ville est de plus en plus liée au secteur tertiaire et développe des rythmes urbains notamment par une augmentation de la cadence ou du nombre d’heures de travail, tout en se dégageant de ses caractéristiques rurales (avec la suppression des temps de pause et de sieste). D’autre part, le rural se manifeste de plus en plus sous la forme exclusive d’un lieu de production, sans relation sociale ou affective à la terre. Mais dans les deux cas, la modernisation de l’agroville et du monde rural n’a jamais mieux été appréhendée qu’au prisme de sa violence intrinsèque.

Following the format of the agrocity, the relationship between the urban and the rural is productively, symbolically and in terms of inhabitancy more separated than ever before. On the one hand, the city is becoming more connected to the service sector and developing urban rhythms, by increasing for example labor intensity and working hours, while becoming increasingly disconnected from its rural components (with the elimination of the work break or napping time). On the other side, the rural becomes more clearly expressed as an exclusive site of production with no social or affective bonds to the land. In both instances, however, the modernization of the agrocity and the rural has never been better understood than through its inherent violence.

Surtout, la poussière et la ceinture agricole de la ville sont plus que des « symboles de violence » ; elles appartiennent en effet à un environnement pollué tangible qui fonctionne comme un moyen d’ordonnancement spatial. Le rôle disciplinaire que joue l’extractivisme dans la topographie des villes rurales opère un lent déplacement des habitants, en portant à la fois atteinte à leur santé (maladies, problèmes de fertilité, décès) et à leurs possibilités en matière de reproduction sociale.

Specifically, the dust and the agricultural enclosure of the city, more than “symbols” of violence, are effectively part of a tangible polluted environment that operates as a means of spatial ordering. The disciplinary role of extractivism in the topography of rural cities operates as a slow displacement of local people by affecting people’s health (i.e., diseases, reproductive issues and deaths) and their possibilities for social reproduction.

Dans la partie suivante, je souhaite revenir sur l’histoire de San Salvador en utilisant une approche postcoloniale pour montrer comment l’empreinte violente du colonialisme, qui a marqué la fondation de la ville, réapparaît au sein de la matrice extractive du développement.

In what it follows, I want to return to the history of San Salvador using a postcolonial framing to show how the violent colonial footprint that founded the city reemerges under the extractive matrix of development.

L’extractivisme et la dialectique rural-urbain : des champs périphériques

Extractivism and the rural-urban dialectics: peripheral fields

San Salvador est fondée à l’époque coloniale, pendant la création des colonies agricoles de l’Entre Ríos[10], par le colonel Malarín ; elle est alors censée contribuer au soutien de la politique d’accueil des immigrants. Le colonel, issu de la bourgeoisie portègne, était un conseiller important du général Roca[11]. Il a été chargé de la gestion stratégique de la population autochtone à l’époque où l’armée menait une campagne de conquête dans le sud des Pampas et en Patagonie. Nommé attaché militaire en 1877, il est envoyé aux États-Unis et en France. Lors de ces deux voyages, il a pour mission d’étudier la manière dont ces deux États assurent l’établissement de leurs frontières intérieures et administrent leurs relations respectives aux autochtones et aux colonies. Pour le directeur du Musée du riz de San Salvador, cette facette du fondateur de la ville offre une perspective particulière sur l’état d’esprit de ses habitants.

The founding of San Salvador occurred during the colonization and creation of agricultural colonies of Entre Ríos.[10] Colonel Malarín founded the city to support the policy of welcoming immigrants. Malarín belonged to the porteño bourgeoisie and was an important adviser to General Roca.[11] He was responsible for the strategic management of the indigenous population during the military campaign of territorial conquest south of the Pampas and in Patagonia. In 1877, he was appointed military attaché and traveled to the United States and France. For both visits, his objective was to study how the state handled the establishment of its interior frontiers as well as its relations to the natives and colonies respectively. As described by the head of the Rice Museum in San Salvador, this aspect of the founder of the city offers a particular perspective on the sensitivity of the inhabitants of San Salvador.

« San Salvador a été la première ville de la province à être fondée à titre privé. Malarín était un type qui, parce qu’il avait un profil militaire, a eu énormément d’influence pendant la Campaña del Desierto [la Conquête du Désert]. Pour moi, cet événement est fondamental, car c’est aussi ce qui fait notre singularité, le truc de dire “je m’approprie certaines choses, j’ai du pouvoir sur elles” […]. Même si la communauté locale ne le sait pas, ou n’en a pas conscience, c’est resté. Malarín, entre les deux stratégies défendues par Roca – tous les tuer ou pas [les autochtones] – Malarín a dit “non, les soldats ne voudront pas tuer tous les Indiens”. Certains d’entre eux, les bébés, les enfants, ont été “appropriés”. Et Roca, qu’est-ce qu’il a fait après ? Il les a amenés aux propriétaires terriens de Cordoba, Mendoza, Buenos Aires, et certains sont allés à Entre Ríos. Une occasion en or ! Je pense que l’appropriation de ces enfants est à l’origine de ceux qui sont devenus plus tard les “créoles” de la région. » (fonctionnaire municipal)

“San Salvador was the first city established privately in the province. Malarín was a guy that, because of his military character, had a lot of influence in the Campaña del Desierto (Desert military campaign). This event is fundamental for me, because this is also our idiosyncrasy, this thing of: ‘I appropriate, I have power over certain things’ […] Even though the community doesn’t know this or is not conscious of it, it stays. Malarín, out of the two strategies that Roca had to advance with the Campaign to the Desert: killing them all [the natives] or not, Malarín, said ‘no, the soldiers won’t want to kill to all the Indians.’ Some of them, the babies, the little ones were appropriated. What did Roca do with them? He took them to the landowners in Cordoba, Mendoza, Buenos Aires and some of them to Entre Ríos. What a chance! I believe the appropriation of those children was later the basis of those who became the creole in this area.” (municipal worker)

Le même esprit utilitariste et d’appropriation se manifeste chez les habitants de San Salvador dans leur rapport à la nature et au rural. La fable folklorique mise en avant par les habitants et la municipalité est liée à l’arrivée des immigrants et à l’essor de la ville. Or l’histoire matérielle de la fondation de San Salvador a été forgée lors de la transition vers le capitalisme, à un moment où la production de la nature est soumise à l’objectif de maximisation des profits du capital, décorrélée de la mise en place de la propriété privée (Wood, 2002).

This same appropriating and utilitarian spirit from the inhabitants in San Salvador is expressed in the perspective over nature and the rural. The folkloric fable highlighted by the locals and the municipality is associated with migrants’ arrival to the colonies and the growth of the town. However, the material history of the formation of the city of San Salvador was forged during the transition to capitalism, when the production of nature is developed under the premise of maximizing capital gains and departing from the formation of private property (Wood, 2002).

« Ça tient surtout au fait que les habitants de San Salvador s’imaginent que la nature est “el campo”. La nature a une valeur tant que c’est un champ agricole. Il y a un concept local pour les broussailles, une formation végétale d’espèces endémiques qui est perçue comme une “sale étendue de terre”. “Sale” signifie qu’il y a des arbres et tout un écosystème fonctionnel qui n’est pas nivelé pour être mis en production. » (militant local et biologiste)

“Much has to do with the fact that the inhabitants of San Salvador have an idea of nature as ‘el campo’. Nature is worth it as long as it is an agricultural field. There is a concept of the native scrublands as a vegetal formation with native species, which it is read here as a ‘dirty tract of land’. ‘Dirty’ means that it has trees and a whole functioning ecosystem which is not leveled to be put into production.” (local activist and biologist)

La perception de la nature comme matière première à mettre au service de l’agriculture réplique les pratiques et les horizons des colonisateurs du XIXe siècle. Comme l’a mis en évidence Fernando Coronil, la terre est devenue un élément constitutif de la fabrication de la modernité. Selon lui, le rôle de l’espace colonial et de ses ressources constitue un aspect fondamental de la configuration des relations sociales capitalistes (2000, p. 248-249). La terre est ainsi réduite à une simple ressource et à un atout économique. Selon l’épistémè moderne, la terre à l’état naturel est considérée par le producteur comme étant à l’abandon ou en friche. Il s’agit de son point de vue d’un champ matériellement et symboliquement périphérique, quelque chose qui se trouve en dehors des relations productives et extractives. Pour le producteur, la campagne est un champ de production et la nature, une matière brute, un objet de valorisation monétaire (Machado, 2014, p. 240).

The perception of nature as primary input or agricultural service replicates the practices and horizons of the colonizers of the 19th century. As Fernando Coronil highlights, land became a constitutive element in the making of modernity. This account recognizes the role of the colonial space and its resources as a fundamental aspect in the configuration of capitalist social relations (2000, p. 248-249). Land is then reduced to a resource and an economic asset. Following the modern episteme, the natural state of the land is read by the producer as abandoned or wasted land. For them, this is a materially and symbolically peripheral field, something that is outside of productive and extractive relations. For the producer, the countryside is a production field and nature is the raw material, an object of monetary valorization (Machado, 2014, p. 240).

Conclusion : un continuum de violence

Conclusion: a violent continuum

Les luttes socio-environnementales sont parvenues à ébranler la perception dominante selon laquelle il existerait une division entre le rural et la ville, tout en nous permettant d’explorer les autres formes possibles de la dialectique rural-urbain. Selon cette grille de lecture, il ne s’agit pas tant d’une division nette, qui ne cesserait de s’intensifier, entre la ville (lieu de services et de consommation) et le champ biotechnologique extractif (avec ou sans agriculteurs), mais d’un continuum de résidus nocifs lié à l’utilisation du territoire, présent à ces différents niveaux, qui par association finit par former un « environnement toxique » (Davis, 2019).

The socio-environmental response challenges the dominant perception of a separation between the rural and the city while allowing us to explore other forms the rural-urban dialectic can adopt. This lens shows that rather than deepening a neat separation between a service and consumption city and a peasant(less) biotechnological extractive field, a continuum of toxic residue within these different planes concerning the use of the territory ties them together in the formation of a “toxic environment” (Davies, 2019).

Dans le contexte du mode extractiviste de production, la division entre les différents usages du territoire (urbain et rural) perd ainsi son caractère distinctif en mettant en évidence la continuité violente qui les relie l’un à l’autre. La violence se manifeste à travers les corps jetables des habitants qui ne saisissent pas les causes de leur maladie, et qui se rendent complices de la transformation de leur ville en une zone de sacrifice.

Under the extractive mode of production, the separation between the different uses of the territory (urban and rural) loses its distinctiveness by highlighting the violent continuity between the one and the other. The violence is evident in disposable bodies of people who do not know how they became sick, and who accept their complicity in the process of turning their city into a sacrificial zone.

La condition de cette modernité périphérique, structurée par les critères du capitalisme extractiviste, nous montre que l’urbain et le rural ne sont pas déconnectés, mais restent encore très fortement liés entre eux par l’appropriation et l’exploitation de la terre et de la nature. Dans ce sens, l’agroville constitue la principale source d’approvisionnement en marchandises (engrais, produits phytosanitaires…) et en services (sites de stockage, machines…) destinés aux champs agricoles. Comme le soulignent Milton Santos et María Laura Silveira, le modèle de l’agroville constitue une géométrie variable qui tient compte de « la manière dont les différentes agglomérations participent au jeu entre le local et le global » (Santos et Silveira, 2001, p. 281).

The condition of this peripheral modernity, organized through the parameters of extractive capitalism, shows us that urban and the rural are not disconnected, and that rural and city are very much still connected by the appropriation and exploitation of land and nature. In this sense, the agrocity operates as the main provider of products (fertilizers, agrochemicals, etc.) and services (deposits, machinery, etc.) for the agricultural fields. As Santos and Silveira highlight, the agrocity model achieves a variable geometry that considers “the way in which the different agglomerations participate in the game between the local and the global” (Santos and Silveira, 2001, p. 281).

Remerciements

Acknowledgement

Je dispose de l’accord oral de l’ensemble de mes interlocuteurs pour les publications universitaires. Cette recherche a bénéficié du soutien du Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET). La réalisation de cet article a également été rendue possible grâce à l’aide de la cartographe Fernanda Zaccaria et de la correctrice Dr Christine Emmett.

I have oral consent from all my interviewees for academic publications. The Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) supported this research. This article was made possible thanks to the support of cartographer Fernanda Zaccaria and copyeditor Dr. Christine Emmett.

Pour citer cet article

To quote this article

Duer Mara, 2023, « Le rapport dialectique entre espaces ruraux et urbains. Réflexions critiques sur la modernisation, la colonialité et l’extractivisme au prisme d’une “agroville” en Argentine » [“The dialectics between rural and urban spaces. Critical reflections on modernization, coloniality and extractivism from an agrocity in Argentina”], Justice spatiale | Spatial Justice, 18 (http://www.jssj.org/article/rapport-dialectique-espaces-ruraux-et-urbains/).

Duer Mara, 2023, « Le rapport dialectique entre espaces ruraux et urbains. Réflexions critiques sur la modernisation, la colonialité et l’extractivisme au prisme d’une “agroville” en Argentine » [“The dialectics between rural and urban spaces. Critical reflections on modernization, coloniality and extractivism from an agrocity in Argentina”], Justice spatiale | Spatial Justice, 18 (http://www.jssj.org/article/rapport-dialectique-espaces-ruraux-et-urbains/).

[1] Le terme de « pueblo fumigado » est attribué à tout village, ville rurale ou agglomération localisé à proximité de champs cultivés et exposé au modèle agro-industriel, lequel se caractérise par l’utilisation de semences transgéniques (notamment de soja) et d’intrants issus de l’agrochimie. Ces sites sont principalement situés dans la province de Buenos Aires et les pampas, ainsi qu’en Mésopotamie argentine, et couvrent désormais la moitié, voire plus, du territoire national. Le vocable populaire de « pueblos fumigados » est employé pour dénoncer les problèmes de santé des populations dus aux fumigations dans leurs localités (Grupo de Reflexión Rural, 2009). Il trouve son origine dans un activisme populaire dès 2001.

[1] The term of pueblo fumigado is given to all the rural villages, towns and cities surrounded by agricultural fields and affected by the agribusiness model that relies on transgenic seeds (mainly soybean) and agrochemical inputs. These sites are mostly found in the province of Buenos Aires, the pampas, and the Mesopotamian area, increasingly covering half or more of the national territory. The popular term of “pueblos fumigados” is used to denounce people’s health issues due to the fumigations in their localities (Grupo de Reflexión Rural, 2009). It was born out of grassroot activism on the question as soon as 2001.

[2] Il existe actuellement vingt rizeries en activité à San Salvador. La majorité d’entre elles sont des entreprises indépendantes de taille moyenne, à côté desquelles on trouve trois grands établissements (Ala, Schmukler, Cooperativa Arrocera) appartenant à trois producteurs locaux. San Salvador est connue comme la « capitale argentine » de la production de riz en raison de sa capacité à structurer l’ensemble de la filière agro-industrielle : semis et récoltes, stockage et transformation, commercialisation. La ville concentre environ 75 % de la capacité totale d’industrialisation du riz en Argentine. En 2021, 63 000 hectares de riz ont été produits à Entre Ríos.

[2] There are currently 20 mills operating in San Salvador. The majority of them are middle size independent local companies, and there are three large mills (Ala, Schmukler, Cooperativa Arrocera) also owned by local producers. San Salvador is known as the “Argentinian capital” of rice production given the capacity to articulate the agro-industrial chain—sowing and harvesting, followed by storage, processing, and finally marketing. The city concentrates about 75% of all rice industrialization capacity in Argentina. By 2021 63,000 hectares of rice were produced in Entre Ríos.

[3] Il s’agit d’un réseau de chercheurs et de médecins, travaillant dans le domaine de la santé, qui s’attache aux effets sur l’être humain de la dégradation de l’environnement causée par la production extractive.

[3] A network of scientists and doctors all working in healthcare and concerned by the effects on human health of the degraded environment resulting from extractive production.

[4] Entre 2011 et 2012, presque un décès sur deux était dû au cancer, contre une personne sur cinq pour l’ensemble du pays (Avila et Difilippo, 2016, p. 29).

[4] Between 2011 and 2012, almost one out of every two deaths was the result of cancer, while in the whole country only one out of every five Argentines dies of oncological causes (Avila and Difilippo, 2016, p. 29).

[5] La municipalité, principal garant du modèle de développement extractif au niveau local, s’est engagée à contrôler les poussières toxiques pendant la saison active (ce qui se traduit dans les faits par des mesures concernant les horaires de transformation du riz et une réglementation quant à l’emplacement des infrastructures toxiques).

[5] The municipality, the main custodian of the extractive model of development at the local level, promised to control the toxic dust during the active season (expressed in policies over schedules for processing the rice and regulating the location of toxic infrastructures).

[6] Certaines infrastructures comme les lieux de stockage d’herbicides, les engins agricoles et les transformateurs de puissance, auparavant situés dans les quartiers périphériques de San Salvador (coïncidant avec la frange la plus pauvre de la population), ont été déplacés hors de la ville. Les pulvérisateurs aéroportés ont également été interdits à proximité des écoles des zones rurales. Désormais, conformément aux règlements internationaux, les producteurs ruraux utilisent des herbicides de catégorie de toxicité IV (classés comme très faiblement ou non toxiques).

[6] Infrastructures, such as the deposits with herbicides, rural trucks and power transformers which were placed at the margins of the city (coinciding with the poorest portion of the population) have been removed from the city. Aerial sprayers have also been prohibited in proximity to rural schools. Finally, rural producers now comply with international regulations and use herbicides of toxicity category IV (categorized as slightly toxic or practically non-toxic).

[7] Appellation forgée par le sociologue Charles Galpin, en référence à des lieux qui ne peuvent être définis en tant que ruraux et qui voient se développer des « dispositifs urbains » comme des technologies financières et des modes de production (Cimadevilla et Carniglia, 2009, p. 5).

[7] The term was coined by the sociologist, Charles Galpin, who made reference to places which cannot typically be defined as rural, and which witness the increasing presence of “urban devices”, such as technological and financial technologies and productive routines (Cimadevilla and Carniglia, 2009, p. 5).

[8] L’estancia était au cœur de la vie sociale dans les campagnes de la pampa, l’espace le plus important de regroupement de population dans les campagnes pendant la période postcoloniale. En termes formels, l’estancia n’était pas une ville ni un espace de vie publique, mais « le territoire privé d’un notable, un territoire délimité non pas par une frontière fixe, mais par les mouvements quotidiens du bétail, des chevaux et des mules à partir des points d’eau » (Albaladejo, 2013, p. 5).

[8] The estancia was the nodal point of social life in the countryside of the Pampa, the most relevant space of population grouping in the countryside during the postcolonial period. In formal terms, the estancia was not a town or a space of public life, but “the private territory of a notable, a territory delimited not by a fixed border, but by the daily movements of cattle, horses and mules from the water points” (Albaladejo, 2013, p. 5).

[10] Dans la région d’Entre Ríos, 171 colonies agricoles ont été fondées : 21 par des institutions nationales et provinciales, 12 par la municipalité locale et 138 par des personnes privées.

[10] In Entre Ríos, 171 agricultural colonies were established, 21 of them were initiated by the national and provincial government and 12 by the local municipal government, while 138 were private.

[11] Julio Argentino Roca (1843-1914), élu deux fois président (1880-1886 et 1898-1904), a été le principal artisan de la conquête de la Patagonie, qui – comble de l’ironie – portait le nom de « Conquête du Désert » (1879). Sa principale préoccupation a été d’établir un État moderne, d’étendre sa mainmise sur le territoire et d’affirmer la souveraineté argentine sur le sud du pays, connu sous le nom de « Patagonie ». La Conquête du Désert a été menée dans l’objectif d’occuper les terres, en déplaçant ou en éliminant la population autochtone, considérée à l’époque comme barbare et comme une entrave au progrès.

[11] Julio Argentino Roca (1843-1914) was twice president (1880-1886, 1898-1904) and the leader of the military conquest of Patagonia, ironically called the “Campaign to the Desert” (1879). His main concern was to establish a modern state, expanding control of the territory and affirming Argentinian sovereignty over the south of the country, known as Patagonia. He led the “Campaign of the Desert” with the objective of occupying the land, displacing and eliminating the native population, seen at the time as barbaric and an obstacle to progress.