Remerciements

Acknowledgements

Les deux auteurs sont chercheurs associés à La Manufacture – HES-SO, à Lausanne et ont bénéficié d'un financement de recherche pour ce projet.

The two authors are associate researchers at La Manufacture – HES-SO in Lausanne and have benefited from a research funding for this project.

Introduction

Introduction

Le 3 mai 2021, l’équipe de recherche du projet Tomason, composée de deux comédien·ne·s, une metteuse en scène, une créatrice sonore, une scénographe et un géographe, s’approche d’un imposant bâtiment à l’architecture moderne, à l’extrémité est du quartier Saint-Gervais, à Genève. Le groupe avance, compact, vers l’entrée, il se retrouve rapidement face à des portes vitrées closes. Derrière elles, on aperçoit encore une billetterie, des affiches de cinéma et le tapis rouge d’un hall. De grandes portes ouvertes laissent entrevoir une immense salle, dont les sièges ont été en partie retirés. L’écran, au fond, est encore visible.

May 3, 2021, the Tomason project research team, consisting of a theatre director, a sound designer and a stage designer (all women), one male geographer and two actors, approach an imposing piece of modern architecture at the eastern end of the Saint-Gervais district in Geneva. The group moves in a phalanx towards the entrance and find itself facing a set of closed glass doors. Behind the doors, a ticket office, movie posters and the red carpet of a hall are still visible. Beyond that there is a glimpse of a huge auditorium, with some of its seats missing. At the back of the hall, the screen is still in place.

Cette immersion collective est la première d’une série de dérives[1] (Debord, 1956), au sein d’un projet de recherche géographique et théâtrale financé par l’école de théâtre La Manufacture, à Lausanne[2], et par le théâtre Saint-Gervais, à Genève[3]. L’équipe, au sein de laquelle ont travaillé ensemble des artistes et un géographe, prépare dans ce cadre une performance artistique à partir d’une enquête inspirée des méthodes des sciences sociales et des concepts de la géographie culturelle.

This group immersion is the first in a series of dérives (Debord, 1956),[1] part of a geographical and theatrical research project funded by La Manufacture theatre school in Lausanne,[2] and by Geneva’s Saint-Gervais theatre.[3] The project team, a collaboration between artists and a geographer, created an artistic performance based on a survey inspired by social science methods and concepts drawn from cultural geography.

Pour l’heure, le groupe d’enquêteur·ice·s constate que les travaux de démantèlement du cinéma Le Plaza ont commencé. C’est le premier vestige dont les habitant·e·s du quartier Saint-Gervais rencontré·e·s dans l’enquête parlent : ce dernier grand cinéma du quartier est doit être démoli pour laisser place à un parking.

So far, the survey group can see that work has started to dismantle the Plaza cinema. This is the first vestige mentioned by inhabitants of Saint-Gervais: the district’s last big movie house is being demolished to make way for a car park.

Saint-Gervais fait partie de ces quartiers de passage, qu’on dirait pensés et construits pour le flux routier. Après une démolition massive de ses infrastructures vétustes dans les années 1930, le quartier est entièrement rebâti à partir des années 1950, son architecture est moderne, ses axes de transport larges et fréquentés.

Saint-Gervais is one of those pass-through districts, seemingly designed and built for traffic flows. After the mass demolition of its ageing infrastructures in the 1930s, work began in the 1950s to rebuild it from the bottom up. Its architecture is modern, its roads wide and busy.

Une interrogation grandit à mesure que l’équipe arpente le quartier, elle concerne l’ensemble des espaces urbains reconstruits dans la seconde moitié du XXe siècle : de quoi se souvient-on quand tout a été rasé, puis reconstruit ?

As the team roams the district, they increasingly wonder about all the urban spaces rebuilt in the second half of the 20th century: what do people remember when everything has been demolished then rebuilt?

Si l’on suit Henri Desbois (s.d.) et Philippe Gervais-Lambony (2017), les traces matérielles de ces changements s’appellent les « tomasons ». Un tomason désigne d’abord la collecte artistique de photographies d’objets urbains ayant perdu leur fonction, mais dont l’espace témoigne d’époques antérieures (Akasegawa, 2009). Philippe Gervais-Lambony qualifie les tomasons de traces « d’un système dont les autres éléments ont été détruits » (2017, § 25). Pour récolter ces tomasons, on les photographie comme des fragments de mémoire, parcelles de nostalgie (Cassin, 2013).

If we follow Henri Desbois (s.d.) and Philippe Gervais-Lambony (2017), the term for these material traces of these lost objects is “tomasons”. It originally referred to the artistic collection of photographs of urban objects that have lost their function but still bear witness to earlier times (Akasegawa, 2009). Philippe Gervais-Lambony describes tomasons as traces “of a system whose other elements have been destroyed” (2017, § 25). They are collected in the form of photographs that act like fragments of memory, parcels of nostalgia (Cassin, 2013).

L’équipe du projet Tomason s’est donc attachée au glanage de ces objets urbains désuets, cherchant à interroger les effets du recours à des concepts de géographie sociale dans le champ artistique. En effet, pour elle, les tomasons révèlent les traces des destructions créatrices urbaines (Veschambre, 2007). Du point de vue théâtral, il s’agit de mettre au jour la valeur de l’oubli dans la pratique de la direction d’acteur·rice : les comédien·ne·s accumulent des observations et des expériences vécues pendant l’enquête et les traduisent sur scène par le seul moyen du récit, par couches, empilées à chaque nouvelle répétition. Cette enquête finalement performée souligne l’apport méthodologique et réflexif de ce croisement disciplinaire.

So in looking for examples of these obsolete urban objects, the Tomason project team sought to explore effects of transposing concepts from social geography to the artistic sphere. They see tomasons as traces of creative destruction at work in the city (Veschambre, 2007). From a theatrical perspective, their aim is to emphasise the value of forgetting in the practice of directing actors: the performers accumulate observations and lived experiences during the survey and transpose them to the stage by narrative alone, accreting layers with each new rehearsal. When finally performed, the study demonstrates the methodological and reflexive value of the combination of disciplines.

Elle cherche d’abord à rendre compte de cette quête de tomasons dans le quartier Saint-Gervais, pour montrer sa portée et ses limites théoriques. Elle propose ensuite d’explorer l’intérêt du recours à des méthodes artistiques pour contourner les limites du concept de tomason. La dernière partie de l’article entend décrire l’intérêt heuristique de la performance artistique lors de la restitution de l’enquête.

This account of the project begins by describing the search for tomasons in the Saint-Gervais district, setting out its scope and theoretical limitations. It then goes on to explore the benefit of using artistic methods to circumvent the limitations of the tomason concept. The final section of the article discusses the heuristic value of artistic performance as a way to report on the survey.

Partir à la recherche des tomasons, une géographie des fantômes

Searching for tomasons, a geography of ghosts

En 2009, Genpei Akasegawa, l’artiste japonais à l’origine du terme de « thomasson[4] » pastichait le Manifeste du parti communiste en ouvrant son Hyperart Thomasson ainsi : « Un spectre hante Tokyo : le spectre du thomasson » (cité dans Desbois, s.d., p. 6). En quoi un tomason peut-il être assimilé à un fantôme ?

In 2009, Genpei Akasegawa, the Japanese artist who coined the term “thomasson”,[4] paraphrased the Communist Manifesto by opening his Hyperart Thomasson in the following way: “A spectre is haunting Tokyo: the spectre of the thomasson” (cited in Desbois, s.d., p. 6). What is the connection between a tomason and a ghost?

Le tomason, figure fantomatique et subversive

The tomason, a spectral and subversive figure

Les fantômes sont des « outils de compréhension de temporalités dissonantes, qui ne sont pas forcément linéaires, et de leurs manifestations en un même lieu » (Barthe-Deloizy et al., 2018, § 6). Or, un tomason, c’est précisément cela : la persistance d’une porte menant sur du vide, celle d’une cabine téléphonique poussiéreuse sans tonalité, celle d’une enseigne délavée, qui toutes témoignent de la désuétude de leur fonction, parce que la ville a – rapidement – changé. L’analogie avec le fantôme permet par ailleurs de souligner une autre de leurs caractéristiques : ils font écho à l’expérience vécue du temps qui passe et de la construction de la mémoire, entre continuités et discontinuités (Gervais-Lambony, 2017, p. 18). La matérialité des tomasons est chargée de symboles et de souvenirs pour les personnes qui ont assisté sans le savoir à leur obsolescence progressive, jusqu’à ne plus les remarquer.

Ghosts are “tools for understanding dissonant temporalities that are not necessarily linear, and their manifestations in a single place” (Barthe-Deloizy et al., 2018, § 6). And this is precisely what a tomason is: the presence of a door that leads nowhere, a dusty telephone kiosk with no ring tone, a faded store sign—all of them bear witness to the redundancy of their function, the result of rapid changes in the city. Making the analogy between tomasons and ghosts is also a way to highlight another of their characteristics: the lived experience of passing time and the building of memories, with its mix of continuities and discontinuities (Gervais-Lambony, 2017, p. 18). The materiality of tomasons is charged with symbols and memories for those who have unwittingly witnessed their gradual obsolescence to the point that they no longer notice them.

En ce sens, le tomason se rapproche de la « survivance » décrite par Georges Didi-Huberman (2009) lorsqu’il s’intéresse aux lucioles, ces expressions dans la pénombre de contre-pouvoirs. La survivance est indestructible, elle peut paraître invisible, mais reste latente, comme une potentialité, elle peut donc ressurgir ailleurs, sous une autre forme. Il faut ici insister sur le caractère subversif des tomasons, présent dès leur invention par Genpei Akasegawa :

In this sense, the tomason is close to the “survival” described by Georges Didi-Huberman (2009) in connection with fireflies, those signals in the penumbra of countervailing powers. A survival is indestructible, it may seem invisible but remains latent, like a potential, and can therefore re-emerge elsewhere, in another form. Here we need to stress the subversive nature of tomasons, a trait already present when they were invented by Genpei Akasegawa:

« Loin d’être uniquement une attitude conservatrice face au changement urbain, la chasse au thomasson est également […] une critique de l’ordre capitaliste. Par son statut de trace sans usage, son inutilité, son absurdité, et son absence de valeur marchande, le thomasson contrarie la recherche de la maximisation du profit et de l’efficacité » (Desbois, s.d., p. 11).

“Far from being a conservative attitude in the face of urban change, hunting tomasons is also […] a critique of the capitalist order. By its status as a trace without a purpose, its pointlessness, its absurdity, its lack of commercial value, the tomason opposes the maximisation of profit and efficiency” (Desbois, s.d., p. 11).

Des traces nostalgiques du passé urbain

Traces of the urban past

Penser les tomasons comme des fantômes permet donc de ne pas les considérer comme des « ruines [qui entretiennent] le souvenir » : ils ne sont bien souvent jamais préservés, au sens patrimonial. On tombe d’ailleurs le plus souvent sur eux comme par hasard, sans même les avoir cherchés. Ils sont plutôt des signes de l’oubli, consubstantiel aux évolutions de la ville (Barthe-Deloizy et al., 2018). À la suite de Carlo Guinzburg (1989, p. 24), chercher les tomasons, c’est s’inscrire dans une méthode de collecte d’indices qui structure les sciences, et voit l’espace urbain comme un palimpseste. Comme une réminiscence qui signifierait notre oubli des profondeurs, le tomason vient signaler le caractère éphémère et transitoire de l’urbain, on devient ainsi nostalgique de ce qui n’existe déjà plus.

To think of tomasons as ghosts is therefore a way to avoid thinking of them as “ruins [that maintain] memory”: they are rarely things that are preserved like heritage. Moreover, they are usually encountered by chance rather than looked for. They are more like signs of forgetfulness, consubstantial with changes to the city (Barthe-Deloizy et al., 2018). Following Carlo Guinzburg (1989, p. 24), to look for tomasons is to espouse a method of collecting clues that is central to the scientific method, in which urban space is seen as a palimpsest. Like a reminiscence that seems to signify our forgetting of the depths, the tomason signals the ephemeral and transitory nature of the urban, causing us to feel nostalgia for something that no longer exists.

C’est précisément cette disparition qui produit la nostalgie, parce qu’elle « tient moins à la persistance d’une mémoire qu’à l’évidence de son effacement » (Roncayolo, 2003, p. 6). Barbara Cassin (2013) interroge, elle, son propre sentiment nostalgique à partir de L’Odyssée. La nostalgie d’Ulysse prend forme dans le fantasme, dans l’appel de cette terre qu’il ne connaît pour ainsi dire plus. Il s’agit donc davantage d’un sentiment d’errance, d’un temps suspendu. Et c’est précisément ce sentiment d’un voyage inachevé, d’une déterritorialisation (Deleuze et Guattari, 1980) que ce travail cherche à interroger avec les spectateurs·rice·s.

It is precisely this disappearance that provokes nostalgia, because it “has less to do with the persistence of a memory than with the evidence of its erasure” (Roncayolo, 2003, p. 6). For her part, Barbara Cassin (2013) draws on The Odyssey to explore her own sense of nostalgia. The nostalgia Ulysses feels is formed in fantasy, in the call of a land that in a sense he no longer knows. So nostalgia here is more to do with the sensation of being unmoored, of suspended time. And it is precisely this sense of an unfinished journey, of a deterritorialisation (Deleuze and Guattari, 1980), that this performance seeks to explore with its audience.

Déconstruire la chasse aux ghost busters

Deconstructing the ghost buster hunt

L’équipe du projet de recherche Tomason a cherché à recueillir cette nostalgie pendant trois semaines d’enquête, comprises dans un mois d’immersion à Saint-Gervais. Le collectif a d’abord dressé une liste de tomasons rencontrés dans les premières dérives. Cette collecte a cependant montré ses limites : la recherche d’objets ponctuels dans l’espace urbain a dès la première semaine de travail produit une extraction des tomasons de leur contexte, leur attribuant un caractère presque de fétiche (Harvey, 1981). Par ailleurs, les tomasons ne disent rien de leur réception par leurs observateur·rice·s quotidien·ne·s, les habitant·e·s. Or, comment travailler sur la mémoire à partir d’un fragment inerte du passé, sans accès aux récits qui les accompagnent ou les produisent ? La seule collecte des tomasons amenait l’équipe dans une impasse.

The Tomason research project team worked to gather together this nostalgia during a three-week survey undertaken during a month of immersion in Saint-Gervais. The group began by drawing up a list of tomasons encountered in the early drifting sessions. However, this collection process revealed its limitations: from the first week, the outcome of searching for contingent objects in urban space was to extract the tomasons from their context, turning them into almost fetishistic objects (Harvey, 1981). Moreover, this said nothing about how the tomasons are perceived by their day-to-day observers, local people. This raises the question of how to work on memory using an inert fragment of the past without access to the narratives that accompany or produce them? Merely collecting tomasons led the team into a cul-de-sac.

La recherche s’est alors attachée à rencontrer des complices, comme l’enquête de terrain en géographie le préconise, et à interroger leur rapport à ces tomasons. Une journaliste, une marchande, un commerçant, deux géographes, un écrivain, une archéologue, une pasteure et un vigile ont pris le temps de transmettre à l’équipe les fragments de leur rapport au quartier, et à ses objets anachroniques. Les discours des complices sont certes pris pour ce qu’ils disent de leurs imaginaires spatiaux, mais aussi pour leur potentiel fictionnel. La parole est alors utilisée pour ce qu’elle révèle des sentiments de nostalgie d’un quartier en changement.

As a result, the focus of the project shifted to the quest for accomplices, as recommended in geographical field surveys, in order to explore their relation to these tomasons. A journalist, a street trader, a shopkeeper, two geographers, a writer, an archaeologist, a priest and a guard, took the time to share with the team fragments of their relationship to the neighbourhood and to its anachronistic objects. The words of these accomplices were captured not only for what they said about their spatial imaginaries, but also for their fictional potential. Speech is therefore exploited for what it reveals of feelings of nostalgia about a changing neighbourhood.

À titre d’exemple, voici ce qu’un commerçant à la retraite, figure centrale du quartier, dit de son arrivée à Saint-Gervais dans les années 1980 (extrait sonore no 1)[5] :

By way of example, here is what a retired shopkeeper, a key figure in the district, said about his arrival in Saint-Gervais in the 1980s (sound extract no. 1):[5]

Extrait sonore no 1 : Entretien mené avec M. El Koury, habitant du quartier © projet Tomason, 2021

Sound extract no. 1: Interview with Mr. El Koury, a resident of the district © project Tomason, 2021

Cette parole, utilisée lors de la performance finale, n’est pas seulement témoignage. Comme son et matière de jeu (texte, personnage, gestuelle), les propos des complices réactivent la mémoire dans une unité de temps et de lieu. La fiction construite à partir de leurs expériences permet d’invoquer les fantômes du quartier, de produire avec leurs mots des récits d’époques passées. Ces récits s’appuyent sur les tomasons physiques comme point de départ, mais s’en détachent rapidement, et les discours des complices sont parsemés de souvenirs, devenant « tomasons symboliques », qui évoquent des nostalgies citadines (Gervais-Lambony, 2012). Ce basculement vers le symbolique explique en grande partie le recours au son, et non au regard, comme méthode de collecte.

These words, which were part of the performance, are not just a personal story. As sound and as theatrical material (text, character, gestures), the words of the accomplices reactivate memory in a unity of time and place. The fiction constructed from their experiences is a way to invoke the ghosts of the district, using their words to produce narratives of past eras. These narratives draw on the material tomasons as a starting point, but quickly move beyond them, and the accomplices’ words are sprinkled with memories that become “symbolic tomasons” which evoke citizen nostalgias (Gervais-Lambony, 2012). This shift to the symbolic register largely explains the use of sound, rather than vision, as a method of collection.

Le son pour sortir du regard omniscient

Sound as a means to escape the omniscient gaze

Faisant écho aux travaux de géographie féministe, Anne Volvey, Yann Calbérac et Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch (2012) insistent sur le statut du regard comme moyen privilégié pour objectiver les relations sociales et construire une forme de regard omniscient. Leur travail souligne que :

Drawing on feminist geography studies, Anne Volvey, Yann Calbérac and Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch (2012) place emphasis on the status of sight as the primary means to objectify social relations and construct a kind of omniscient gaze. In their work, they argue that

« l’enquête de terrain classique, qui fonde la collecte et la corrélation de données sur l’observation, est définie par les féministes comme “a performance of power” (Rose, 1996, p. 58) – particulièrement, “an inappropriate performance of colonizing power relations” (Sharp, 2005, p. 306). La pratique (work) de terrain, calquée sur celle de l’exploration, évolue entre possession par l’arpentage, pénétration par le regard et contrôle par le recouvrement exhaustif d’un espace extérieur (field ou land). » (Volvey et al., 2012, p. 447)

“The classic field survey, in which the collection and correlation of data are based on observation, is defined by feminists as “a performance of power” (Rose, 1996, p. 58)—particularly, “an inappropriate performance of colonising power relations” (Sharp, 2005, p. 306). The practice of fieldwork, inspired by the model of exploration, operates between possession by measurement, penetration by the gaze and control by the comprehensive coverage of an external space (field or land) (Volvey et al., 2012, p. 447).

Dans la lignée de ces écrits, le projet de recherche a tenté de « sortir de la chasse » aux tomasons. Le roman d’anticipation Les Furtifs (Damasio, 2019) imagine des êtres hybrides entre chair et vibration, invisibles, et qui échappent au contrôle d’une société dystopique. Un père recherche sa fille devenue furtive, et au cours de son enquête, il découvre que les furtifs sont faits de particules en vibration, de son. Sa trajectoire dans le roman est celle d’un désapprentissage de la chasse.

Influenced by these writings this research project sought to “move away from the hunt” for tomasons. The futuristic novel Les Furtifs (Damasio, 2019) imagines “stealthy” beings, beings that are invisible, a hybrid of flesh and vibration, which are thus able to escape the control of a dystopian society. A father is looking for his daughter, who has become one of these beings, and during his search discovers that they are made of vibrating particles, i.e., of sound. In the course of the novel, he learns to abandon the hunt.

Cherchant à ne pas reproduire ces travers de ghost busters, le dispositif d’enquête repose sur le recours au son, du recueil de témoignages à la performance finale. Le son fonctionne alors sur le mode de la suggestion plutôt que sur celui de l’affirmation, comme l’indique Vinciane Despret :

In an attempt to avoid these ghost buster errors, the survey apparatus relies on the use of sound, from recordings of personal accounts to the ultimate performance. Sound functions by means of suggestion rather than assertion, as Vinciane Despret indicates:

« Qu’est-ce que le son change dans notre rapport au monde ? […] Quand on est dans l’ordre du visuel, on est dans l’ordre de la certitude. […] La vérité visuelle est une vérité référentielle : je vois cette chose et je sais à quoi elle réfère. On est dans l’ordre de la vérité où une certitude va s’installer. […] La quête de sons est une quête de curiosité qui respecte le fait qu’on ne sait pas tout et qu’on n’a pas accès à tout, alors que le visuel nous donne une sorte de primauté d’accès, on est presque maîtres en la demeure quand on est dans le visuel, alors que dans le sonore on doit rester des apprentis[6]. »

“What is it that sound changes in our relationship to the world? […] When we are in the visual register, we are in the dimension of certainty. […] Visual truth is a referential truth: I see this thing and I know what it refers to. This is a register of truth in which a certainty will become established. […] The quest for sounds is a curiosity-driven quest which respects the fact that we don’t know everything and we don’t have access to everything, whereas the visual gives us a sort of primacy of access. In the visual dimension, we are almost masters of the house, in sound we remain apprentices.”[6]

Au cours de l’enquête, l’équipe s’est attachée, comme principe méthodologique, à ne pas prendre de photographie pour faire du son le moyen privilégié de représentation fantomatique.

During the survey, as a methodological principle, the team chose not to take photographs so as to make sound a primary means of representing the ghost world.

Performer la carte mentale : observer, empiler, oublier

Performing the mind map: observing, stacking, forgetting

Parallèlement, les comédien·ne·s étaient invité·e·s à produire, en début de recherche, une carte mentale papier du quartier.

In parallel, at the start of the research, the actors were asked to produce a mind map of the district on paper.

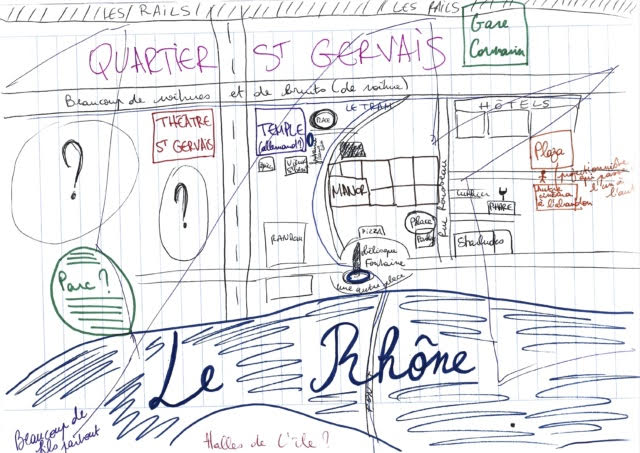

Figure 1 : Carte mentale du quartier Saint-Gervais © projet Tomason, 2021

Figure 1: Mind map of the Saint-Gervais district © project Tomason, 2021

Sur cette carte mentale, le quartier Saint-Gervais prend forme à travers ses structures : le Rhône en bleu sur la partie basse, des axes routiers en son centre et les rails du train sur le bord supérieur. On distingue par ailleurs des lieux marquants, de la gauche vers la droite : le théâtre Saint-Gervais en rouge, le temple qui lui fait face en violet, suivi du supermarché Manor et, pour finir, sur le cinéma Le Plaza en rouge à l’extrémité droite de la carte. Cette dernière dessine une constellation d’objets urbains non contigüs, reliés par le souvenir des dérives collectives.

On this mind map, the Saint-Gervais district is given shape through its structural features: the Rhône in blue on the lower part, roads in the centre and the railway tracks on the upper edge. In addition, the map includes landmark places. From left to right: Saint-Gervais Theatre in red, the temple opposite it in mauve, followed by the Manor supermarket and, to finish, the Plaza cinema in brown on the right edge of the map. The map figures a constellation of noncontiguous urban objects linked by the memory of group drifting sessions.

Cette carte (figure 1), très imprécise et imparfaite du point de vue sémiologique, a inspiré un exercice de direction d’acteur·rice, dans lequel iels étaient invité·e·s à raconter et à jouer leur carte dans l’espace de la salle de répétition. Les comédien·ne·s ne disposaient pas de support textuel, mais d’une expérience orale, et, n’ayant accès qu’aux traces des répétitions passées par l’enregistrement sonore, c’est en se souvenant de la composition de la carte dans l’espace qu’iels ont progressivement construit une partition corporelle et verbale décrivant le quartier. Au lieu d’accumuler des matériaux d’enquête de manière exhaustive, comme le ferait une cartographie par arpentage ou par collection de lieux, la carte performée devient un affleurement[7] mémoriel des expériences retenues, mais aussi, et c’est tout aussi important, oubliées. À mesure que la carte est jouée, rejouée, répétée, se dessine une succession de fragments d’expériences des comédien·ne·s dans leurs dérives. Par leurs récits et leurs émotions, les iels proposent dès lors des traductions, toujours partielles et partiales du terrain. En cela, leur interprétation se rapproche d’une expérience sensible de tomason : comme si pour performer une carte dans un studio de théâtre, il fallait certes retenir des lieux, mais aussi en laisser disparaître. Cette méthode rejoint le travail du metteur en scène Thom Luz dans When I Die (2013) qui invoque le fantôme de grands compositeurs, où les interprètes développent un rapport émotionnel particulier avec leur instrument. Les objets deviennent dépositaires d’une relation entre les vivants et les morts et tout le spectacle s’articule autour d’une danse d’objets et de sons de fantômes.

This map (figure 1), inaccurate and imperfect as it is from a semiological point of view, inspired an acting exercise in which the director asked the actors to relate and act out their map in the rehearsal room. They didn’t work from a text, but from oral experience alone and, because they only had access to the traces of past rehearsals in the form of sound recordings, it was by remembering the layout of the map in space that they were gradually able to improvise the movements and words to describe the district. Instead of accumulating comprehensive survey data by measurement or situating places, as would happen in cartography, the map performance becomes a memory outcrop[7] of the experiences enacted, but also—and equally importantly—of the experiences forgotten. As the map is enacted, re-enacted, rehearsed, a succession of fragments of the actors’ drifting experiences emerges. By the narratives and their emotions, the actors thus come to produce translations, inevitably always partial in both senses of the word, of the space. In this, their interpretation resembles the experience of a sensory tomason, as if, in order to perform a map in a theatre studio, they not only had—of course—to remember places, but also to let some fade away. This method links with the work of the theatre director Thom Luz in When I Die (2013), invoking the ghosts of great composers, where the musicians develop a particular emotional relationship with their instruments. Objects become the repositories of a relationship between the living and the dead, and the whole play is orchestrated around a dance of ghost objects and sounds.

Ici, ce sont les lieux qui deviennent des cadres du récit, incorporés et inconscients. Ils ne sont certes plus présents dans la parole des comédien·ne·s, mais le demeurent dans leur manière de les contourner, de les passer sous silence. Dans l’extrait sonore qui suit (extrait sonore no 2), la cartographie jouée montre plusieurs étapes d’un processus de cartographie classique : délimitation des contours, justification des frontières, désignation des centres névralgiques.

In this performance, it is places that become the frames for the narrative, embodied and unconscious. Of course, they are no longer present in the lines spoken by the actors, but remain so in the way that the actors circumvent them, leave them unspoken. In the sound extract that follows (sound extract no. 2), the enacted map shows several stages in a process of ordinary cartography: delimitation of outlines, justification of borders, identification of nerve centres.

Extrait sonore no 2 : Enregistrement de la carte spatialisée en studio de théâtre © projet Tomason, 2021

Sound extract no. 2: Theatre studio recording of the spatialised map © project Tomason, 2021

Seulement, ici, la cartographie proposée est aussi celle de ce qui « ne nous intéresse pas » et qu’il serait impossible de représenter sur un plan : les extraits inutiles des entretiens, l’immeuble qui se dresse face à nous et dont on ne sait que faire, et le tomason, qui interpelle par son anachronisme et sa désuétude. En représentant le matériau inutile dans la carte, la performance propose de faire cas des matériaux ratés, bricolés, en trop, pourtant au cœur des sciences sociales. Enquêter sur les tomasons permet d’intégrer et de visibiliser les tentatives, parfois avortées, dans la construction du savoir géographique, en cherchant des dispositifs d’écriture qui rendent compte de cette matière.

Except that here, the cartography also includes what “doesn’t interest us” and would be impossible to represent on the map: discarded interview extracts, the building in front of us that we don’t know what to do with, and the tomason, which stands out for its anachronism and redundancy. In representing useless material on the map, the performance enacts material that is failed, makeshift, surplus, all the stuff that is central to the social sciences. Conducting a survey of tomasons is a way to incorporate and give visibility to sometimes abortive attempts in the construction of geographical knowledge, by looking for methods of writing that take this material into account.

Représenter la nostalgie : un rituel géographico-théâtral

Representing nostalgia: a geographical-theatrical ritual

Le 7 novembre 2021, une trentaine de spectateur·rice·s debout sirotent un pastis dans la salle vitrée du 6e étage du théâtre Saint-Gervais. Les lumières de la ville envahissent la salle, et Julien Doré chantonne avant de laisser la place à « My Hometown » de Bruce Springsteen (Gervais-Lambony, 2020). Le clocher du temple, adossé au théâtre, sonne 18 h, le soleil se couche, mais on aperçoit encore la silhouette de la montagne du Salève qui veille sur Genève.

It is November 17, 2021. Some thirty audience members stand sipping a pastis in the glass room on the 6th floor of Saint-Gervais Theatre. The lights of the city shine into the room, Julien Doré croons for a while before giving way to Bruce Springsteen’s “My Hometown” (Gervais-Lambony, 2020). The temple bell tower behind the theatre strikes six, the sun is going down, but the silhouette of Mount Salève is still visible, watching over Geneva.

Enquête et fiction

Survey and fiction

L’équipe de recherche a organisé cette verrée en hommage à monsieur El Khoury (extrait sonore no 1), un habitant qui nous a raconté son arrivée dans le quartier, pour clôturer chaque représentation de la performance. Avec elle, c’est non seulement cette recherche qui s’achève, mais aussi le rituel géographico-théâtral. Lors de trois soirées successives, le public a eu accès au sentiment nostalgique pour des lieux qu’il n’a pas nécessairement parcourus, par un dispositif scénique de montage et d’immersions sonores.

The research team has organised this drinks party as a tribute to Mr. El Khoury (sound extract no. 1)–a resident who had told us about his arrival in the district—as a way to bring closure to each performance. It punctuates not only the end of the study, but also of the geographical-theatrical ritual. On three successive evenings, the spectators have experienced nostalgic feelings about places that they have not necessarily visited, through immersion in sound and dramatic expression.

Pour cela, les enquêteur·rice·s ont cherché à convoquer la spatialité et les nostalgies propres à chaque spectateur·rice. Le lieu de la représentation s’est avéré central : le théâtre Saint-Gervais est au cœur du quartier. Cette ancienne maison des jeunes et de la culture à l’architecture moderne est un lieu culturel emblématique. Le choix de la salle du 6e étage est déterminant : il s’agit d’une salle de répétition basse de plafond, vitrée sur deux côtés, avec une vue semi-panoramique sur le quartier. Le parquet, les tons marron bordeaux, les stores roulants, les placards en contreplaqués et les colonnes en béton granuleux créent une ambiance d’un autre temps. L’équipe installe huit grandes tables blanches au centre, dans le premier tiers de la salle, reproduisant ainsi, en l’agrandissant, notre bureau collectif ainsi qu’une trentaine de chaises en coque empilables (type salle des fêtes). Un espace de jeu est laissé libre entre cette table et le fond vitré (figure 2).

To achieve this, the researchers have tried to address the spatiality and nostalgias specific to each audience member. The location of the performance has proved crucial: Saint-Gervais theatre is at the heart of the district. This former youth and culture centre, with its modern architecture, is an iconic cultural space. The choice of the room on the 6th floor is also essential: it is a low-ceilinged rehearsal room, with glass on two sides and a panoramic view over the district. The parquet floor, the chestnut colour tones, the roller blinds, the plywood cupboards and the granular concrete columns create the atmosphere of a different time. The team places eight big white tables in the centre, in the front third of the room, reproducing an expanded version of our group office, as well as some thirty stackable plastic chairs (village hall style). A performance space is left free between this table and the glass rear wall (figure 2).

Figure 2 : Photographie de la performance Tomason, 2021 © Ivo Fovanna

Figure 2: Photograph of the performance of Tomason, 2021 © Ivo Fovanna

Les stores sont fermés lorsque le public entre ; ils sont ensuite ouverts de manière progressive au cours de la performance. Les néons sont allumés et le public est réparti autour de la table sur laquelle sont disposés cartes mentales, carnets de terrain et ordinateurs. Une machine à café se déclenche à plusieurs reprises de manière aléatoire.

The blinds are closed when the audience arrive, then are gradually opened during the performance. The neon lights are on and the audience is spaced around the table where mind maps, field notebooks and computers are laid out. A coffee machine gurgles into life several times at random moments.

La metteuse en scène présente le projet et chacun·e des membres de l’équipe, ainsi que leurs types d’adresses et de prises de parole, propres à leur spécialité : comédien·ne·s, créatrice sonore, géographe, metteuse en scène. Chaque étape de la recherche est mentionnée : hypothèses, liste des tomasons et des complices, récits de dérives et d’anecdotes (Calcine et Opillard, 2022), désaccords sur la marche à suivre, échecs de prises de contact, références théoriques. Chaque membre occupe une position particulière : une comédienne, arrivée au dernier moment dans le processus, pose sans cesse des questions, un comédien donne à entendre ses doutes d’enquêteur, oscillant entre ce qu’il connaît et ses accès de paranoïa (Boltanski, 2012), la metteuse en scène donne accès aux errances de l’enquête, le géographe recentre le débat sur les questions théoriques et spatiales, et la créatrice sonore distille son journal de bord sonore.

The director introduces the project and each of the team members, as well as the types of address and speech specific to their speciality: actor, sound designer, geographer, director. Every stage in the research is covered: hypotheses, list of tomasons and accomplices, narratives and anecdotes about the drifting process (Calcine and Opillard, 2022), disagreements about how to proceed, failed encounters, theoretical references. Each member occupies a particular position: an actress who joined the process at the last moment constantly asks questions, an actor gives voice to his doubts as a researcher, fluctuating between what he knows and his attacks of paranoia (Boltanski, 2012), the director talks about the ups-and-downs of the survey, the geographer refocuses the debate on theoretical and spatial questions, and the sound director gives a summary of her sound log.

Parallèlement, un comédien s’attache à délimiter le périmètre de la recherche, « pour bien commencer » le rituel. Il permet ainsi de circonscrire, pour le public, le terrain de recherche, à savoir le quartier, concentré ici dans la salle par un effet de réduction. Par ailleurs, un brouillage entre réalité et fiction est perceptible dans le choix des costumes : vêtements de ville, avec un léger décalage (le comédien est entièrement habillé de bleu). Une première énigme (Boltanski, 2012) apparaît : une comédienne est muette, elle revêt un costume aux couleurs bariolées et un chapeau.

In parallel, one actor tries to delimit the scope of the research, in order to get the ritual off “to a good start”. In this way, for the audience, he circumscribes the research perimeter, in other words, the district, here concentrated within the microcosm of the room. In addition, a blurring between reality and fiction is visible in the choice of outfits: street clothes, but just slightly offbeat (the actor is dressed entirely in blue). A first mystery (Boltanski, 2012) arises: one actress, dressed in a multicoloured outfit and a hat, remains silent.

Brouiller les pistes

Sowing confusion

Un glissement allant de l’enquête à la performance s’effectue lentement. Alors que les projecteurs de théâtre s’allument, les néons s’éteignent. Les comédien·ne·s entament la scène de spatialisation de leurs cartes du quartier (figure 3), en simultané. La qualité du jeu donne alors un effet d’improvisation et d’erreurs, iels semblent chercher dans leurs souvenirs, les observations, les odeurs, les anecdotes, et inventer en direct.

Slowly, a slippage occurs from survey to performance. The spotlights are switched on, the neon lights switched off. The actors begin a live enactment of the spatialisation of their district maps (figure 3). The quality of the acting creates an effect of improvisation and error. They seem to be trying to remember observations, smells, anecdotes, to be making things up as they go along.

Figure 3 : Photographie de la cartographie performée, Tomason, 2021 © Ivo Fovanna

Figure 3: Photograph of the mapping performance, Tomason, 2021 © Ivo Fovanna

Des traces de l’enquête parsèment la performance et jouent sur les juxtapositions d’écritures fragmentaires et minoritaires (Deleuze et Guattari, 1980). Si le géographe et la créatrice sonore parlent depuis leur position professionnelle, les comédien·ne·s passent de leur propre rôle à la composition de personnages (figure 4), leurs textes étant puisés dans les paroles brutes de l’enquête, les leurs et celles des complices/enquêté·e·s. Lorsque la comédienne restée jusque là silencieuse prend pour la première fois la parole, c’est avec des mots qui ne sont visiblement pas les siens, mais bien ceux d’un personnage qui parle du quartier.

Traces of the survey are scattered through the performance and play on juxtapositions of fragmentary and secondary styles (Deleuze and Guattari, 1980). While the geographer and the sound designer speak from their professional stance, the actors shift from their own role to the composition of characters (figure 4), drawing their texts from the raw speech of the survey, their own words and the words of the accomplices and interviewees. When the actress who has so far been silent speaks for the first time, the words are visibly not her own, but those of a character talking about the district.

Figure 4 : Photographie du re-enactment de la marchande, Tomason, 2021 © Ivo Fovanna

Figure 4: Photograph of the re-enactment of the street trader, Tomason, 2021 © Ivo Fovanna

Ce matériau collecté a été transformé au cours des répétitions, vers une fictionnalisation. Cette pratique emprunte aux outils du théâtre documentaire et de l’histoire orale, sous la forme d’un re-enactment, puis à l’aide d’une oreillette, comme le propose l’artiste Julia Perazzini dans Holes and Hills (2016). Elle donne à entendre les voix et les corps de fantômes de femmes connues ou inconnues qui croisent sa route. La performeuse surfe sur la brèche d’une identité plurielle. De la même manière dans Tomason, on entend ensuite des bribes de la voix d’une marchande dans une création sonore diffusée pendant que les deux comédien·ne·s dansent, dans la dernière partie de la performance. Ainsi ces persistances de l’enquête de terrain constituent des énigmes pour le public qui n’a pas accès à l’expérience première à laquelle elles se rattachent. Il ne perçoit que des bribes et des oublis, en ce sens il peut faire l’expérience en direct d’un sentiment nostalgique, de l’apparition de tomasons.

The material collected has been transformed in the course of the rehearsals, partially fictionalised. This practice draws on the tools of documentary theatre and oral history, in the form of a re-enactment, then using an earpiece, as embodied by Julia Perazzini in Holes and Hills (2016), where the artist gives expression to the voices and bodies of phantoms of known or unknown women who cross her path. The performer surfs in the holes of a plural identity. Similarly in Tomason, we next hear scraps of the voice of a street trader in a sound design creation, while the two actors dance in the last part of the performance. As a result, these residues of the field survey are mysteries for the audience, who have no access to the initial experience from which they stem. The audience sees only scraps and omissions. In this respect, they directly experience a sense of nostalgia, the appearance of tomasons.

En parallèle, des extraits sonores de l’enquête sont diffusés tout au long de la performance. Ils constituent une écriture dans une logique de montage, parallèle à l’écriture scénique, mais en la complétant, pour ponctuer le récit, proposer un contrepoint, un cut, ou un écho théorique à cette expérience empirique de la représentation.

In parallel, sound extracts from the survey are broadcast throughout the performance. They constitute an entry in an editing process, parallel but complementary to the stage entry, punctuating the narrative, providing a counterpoint, a cut, or a theoretical echo to this empirical experience of representation.

Dire adieu au quartier

Saying goodbye to the district

La dernière partie de la performance délaisse peu à peu la parole. Elle juxtapose d’abord trois histoires, en simultané, comme un empilement aléatoire et inaudible des couches qui culmine dans un climax (figure 5), et se termine par la danse des deux comédien·ne·s dans la semi-pénombre.

The last part of the performance gradually abandons speech. It first juxtaposes three stories, simultaneously, like a random and inaudible heaping of layers that culminates in a climax (figure 5), and ends with the two actors dancing in the semi-twilight.

Extrait sonore no 3 : Les comédien·ne·s dansent dans la semi-pénombre © projet Tomason, 2021

Sound extractor no. 3: The actors dance in the semi-twilight © project Tomason, 2021

Cette danse (extrait sonore no 3) restitue les rencontres avec deux complices et met l’accent sur un sentiment nostalgique qui s’attacherait alors davantage aux sensations, à la mémoire sonore, olfactive et tactile des lieux.

This dance (sound extract no. 3) reproduces the encounters with two accomplices and expresses a feeling of nostalgia that is more connected with sensations, with the memory of the sound, smell, and touch associated with places.

Enfin, une visite guidée individuelle, diffusée dans des iPod mis à disposition, est proposée aux spectateur·rice·s. Iels sont invité·e·s à fermer les yeux. Certain·e·s sont lentement amené·e·s jusqu’aux fenêtres, iels ouvrent les yeux face à la ville nocturne.

Finally, the spectators are given iPods that broadcast an individual guided tour. They are invited to close their eyes. Some of them are led slowly to the windows, and open their eyes to see the city at night.

Cette visite propose d’accompagner le public dans le quartier, les voix des deux comédien·ne·s servant de guide, enregistrées au préalable. Mais contrairement à ce que l’on pourrait attendre d’une enquête scientifique ou documentaire, ce sont les choses insignifiantes qui retiennent l’attention : une girafe en plastique dans un jardin public, le bruit des graviers, les corps saints qui hantent la rue du même nom. En jouant sur les juxtapositions de perceptions (sons de la ville, corps dans la salle, lumières extérieures et obscurité intérieure) et par un effet d’agrandissement cette fois, les spectateur·rice·s expérimentent une dérive tout en restant dans la salle de théâtre. Dans cette perspective, on peut dire que l’expérience théâtrale est elle-même devenue tomason, faite d’un empilement de couches de survivances, un montage de nostalgies empruntées et vouées à faire écho à celles du public. Une fois les yeux ouverts, la verrée permet à l’assemblée de se mettre dans la position de nouveaux·elles arrivant·e·s dans le quartier, le rituel est terminé et un pot de bienvenue est organisé par et pour les nouveaux·elles venu·e·s. Il s’agit à la fois d’une arrivée et d’un adieu.

The tour offers to escort the audience through the district, guided by the pre-recorded voices of the actors. But rather than what might be expected in a scientific or documentary survey, the tour focuses on insignificant things: a plastic giraffe in a public garden, the noise of gravel, the sacred bodies that haunt the street of the same name. Through the play on perceptual juxtapositions (sounds of the city, bodies in the room, exterior lights and interior darkness) and this time through an effect of enlargement, the spectators have the experience of drifting while remaining within the auditorium. From this perspective, it can be said that the theatrical experience has itself become a tomason, made up of stacked layers of survivals, an assembly of borrowed nostalgias intended to echo those of the audience. Once they have opened their eyes, the drinks party enables the assembled spectators to adopt the position of new arrivals in the neighbourhood, the ritual is over, and a welcome drink is organised by and for the newcomers. It is both a welcome and a farewell.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Le recours à un concept issu du monde artistique, puis réinvesti par la géographie a donc ici permis de construire une forme théâtrale alimentée par les outils méthodologiques propres à cette discipline scientifique. Le rituel géographico-théâtral rend ainsi visible et sensible les bricolages de l’enquête, faisant place à chaque tentative, avortée ou non, au cours de la recherche, tout en cherchant à produire émotions et imaginaires nostalgiques pour des lieux pourtant inconnus du public. C’est là la force du rendu performatif qui, épaissi par l’enquête géographique et fictionnalisé par l’écriture théâtrale, permet de plonger dans la complexité des sensations et des imaginaires géographiques, et fait appel à ce qu’il y a de commun chez les des spectateur·rice·s.

A concept originating in the arts world, then readopted by geography, has been employed here to construct a theatrical form enriched by methodological tools specific to the scientific discipline. In this way, geographical-theatrical ritual is used to give physical and tactile expression to the tinkerings of the survey, making room for every start and false start in the research, while seeking to arouse in the audience emotions and nostalgic imaginaries even for places unfamiliar to them. That is the power of performative expression which, fleshed out by the geographical survey and fictionalised by theatrical writing, immerses the spectators in the complexity of geographical sensations and imaginaries, and summons up what they have in common.

Imaginé dans le quartier de Saint-Gervais, ce rituel géographico-théâtral n’a pas vocation à demeurer à Genève, mais cherche précisément à prendre forme là où l’enquête est possible. Chaque tentative est donc l’objet d’une inscription sur une carte interactive, sur laquelle on peut d’ores et déjà trouver les résultats des deux premiers exercices[8]. La démarche est ainsi reproduite en avril 2023 avec les étudiant·e·s en master Mise en scène de La Manufacture, à Lausanne.

Imagined in the district of Saint-Gervais, this geographical-theatrical ritual does not need to remain in Geneva, but rather seeks to take shape anywhere where enquiry is possible. Every attempt is therefore recorded on an interactive map, on which the results of the first two exercises can already be found.[8] The exercise was thus repeated in April 2023 with students on the Stage Production programme at La Manufacture, in Lausanne.

Figure 5 : L’équipe de recherche de Tomason dansant sur le générique de Ghost Buster, Tomason, 2021 © Ivo Fovanna

Figure 5: The Tomason research team dancing on the credits of Ghost Buster, Tomason, 2021 © Ivo Fovanna

Pour citer cet article

To quote this article

Opillard Florian, Calcine Sarah, 2023 « Collecter, écrire et performer les nostalgies citadines. En quête de tomasons à Saint-Gervais, Genève », [“Collecting, writing and performing urban nostalgias/ Looking for tomasons in Saint-Gervais, Geneva”], Justice spatiale | Spatial Justice, 18 (http://www.jssj.org/article/collecter-ecrire-performer-les-nostalgies-citadines-en-quete-de-tomasons-a-saint-gervais-geneve/).

Opillard Florian, Calcine Sarah, 2023 « Collecter, écrire et performer les nostalgies citadines. En quête de tomasons à Saint-Gervais, Genève », [“Collecting, writing and performing urban nostalgias/ Looking for tomasons in Saint-Gervais, Geneva”], Justice spatiale | Spatial Justice, 18 (http://www.jssj.org/article/collecter-ecrire-performer-les-nostalgies-citadines-en-quete-de-tomasons-a-saint-gervais-geneve/).

[1] Empruntée aux situationnistes, la dérive consiste à parcourir la ville à partir d’une contrainte qui varie à chaque tentative. Elle invite les comédien·ne·s à errer dans la ville en cherchant le contact avec de potentiels complices.

[1] A situationist practice, la dérive (drifting) consists in explorations of the city conducted each time under a different constraint. In this case, the actors were asked to wander around the city and approach potential accomplices.

[2] Une description du projet est accessible sur le site Internet de La Manufacture, HES.SO Lausanne.

[2] A description of the project can be found on the website of La Manufacture, HES.SO Lausanne.

[4] L’orthographe du terme a d’abord pris cette forme en référence à Gary Thomasson, un joueur de baseball qui, manquant toutes ses balles et assigné au banc de touche, n’était que l’ombre de lui-même (Desbois, s.d.).

[4] The word was originally spelt in this way in reference to Gary Thomasson, a baseball player who missed every strike and was relegated to the substitutes bench, a shadow of his former self (Desbois, s.d.).

[5] Les extraits sonores ont tous été captés sur le vif, lors de l’enquête préalable à la performance finale, ce qui peut parfois altérer la clarté du son.

[5] The sound extracts were all recorded live, during the survey that preceded the final performance, which can sometimes distort the clarity of the sound.

[6] Transcription d’un extrait de l’émission de France Culture, La Grande Table, de Olivia Gesbert, épisode du 23 février 2021 (https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/podcasts/la-grande-table-idees/vinciane-despret-une-ecologie-de-la-cohabitation-8519124, écouté le 12 mai 2022).

[6] Transcrip of an extract from the France Culture programme, La Grande Table, by Olivia Gesbert, episode broadcast on February 23, 2021 (https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/podcasts/la-grande-table-idees/vinciane-despret-une-ecologie-de-la-cohabitation-8519124, listened to on May 12, 2022).